Detroit wants to extend comeback to neighborhoods. So far, it’s a slow go.

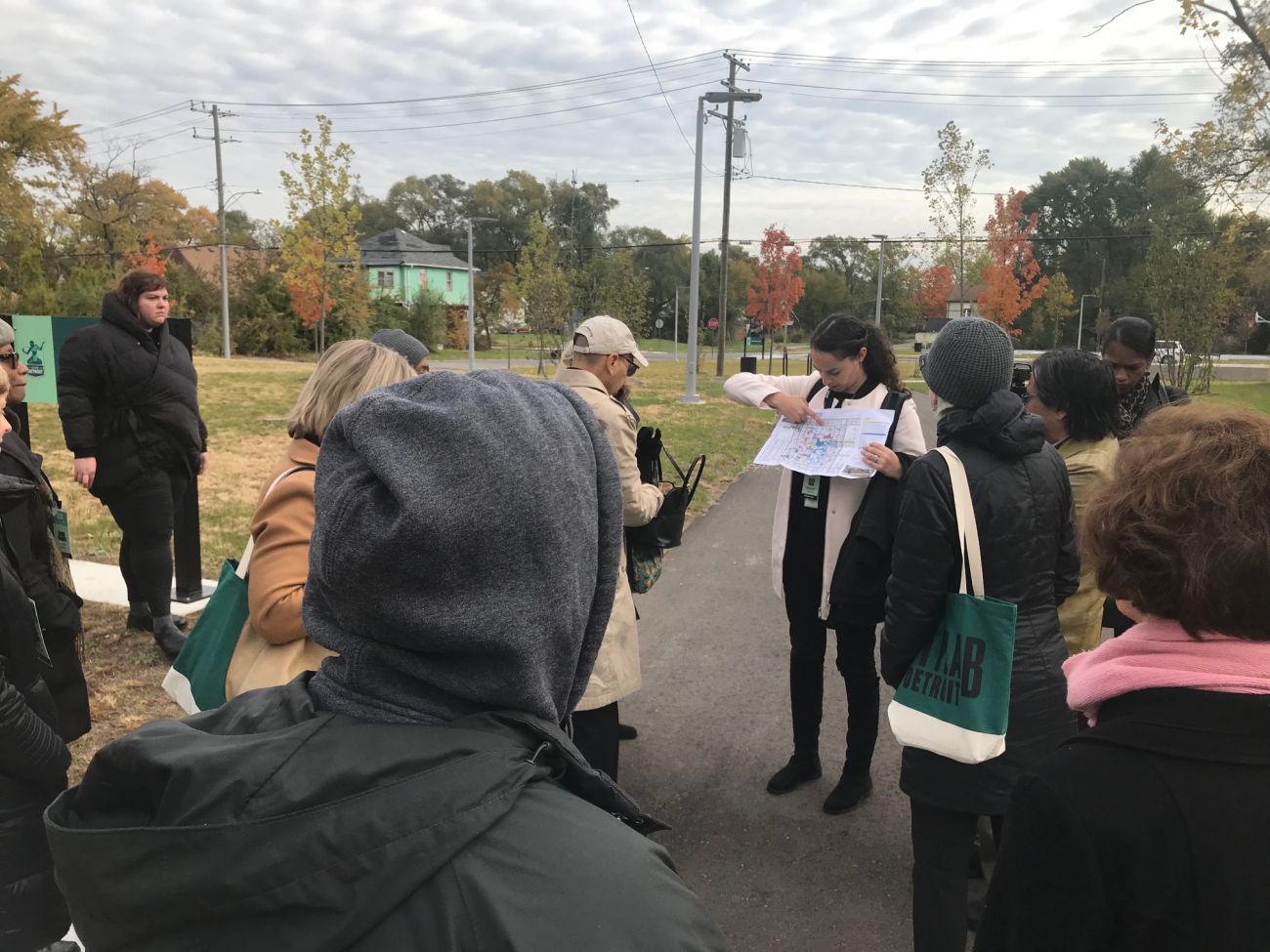

When global urban leaders met in Detroit last month, they traveled by bus to the city’s Fitzgerald neighborhood with cameras in hand.

They wanted to see the huge revitalization effort that the city’s planning director, Maurice Cox, bragged about during the CityLab conference; the one Mayor Mike Duggan said in 2017 is a “really important test” of whether Detroit’s blighted neighborhoods can come back like trendy areas such as downtown and Midtown.

On the tour, led by a city planning official, the visitors saw cleared vacant lots that were renamed “meadows,” an urban garden and the new Ella Fitzgerald Park that looks like it plucked from a suburb and dropped amid boarded-up homes.

“I’m very impressed by this park that they’ve created. It’s wonderful,” said Justin Garrett Moore, executive director of the New York City Public Design Commission.

The tour guide barely mentioned that the project is a year behind schedule. In 18 months, developers have only fixed and sold three homes in the project that promises to rehab 100.

City officials still maintain they can rehab, sell and lease 97 more houses over the next two years.

Related stories:

- Is Detroit finally turning the corner?

- Poverty is Detroit’s biggest problem. Gentrification doesn’t come close.

- Is your Detroit neighborhood primed for a rebound? (interactive map)

- Poor people at risk of eviction as tax credits expire and Detroit revives

- Real estate is hot in Detroit. But its top owner, the city, isn’t selling.

- Rising rents. Falling wages. Detroit’s poor face housing crisis.

- Banks are lending again in Detroit … if you live in the right neighborhood

- Tax breaks for poor neighborhoods steered to booming pockets in Detroit

There’s a lot at stake. City officials want to replicate the $4 million Fitzgerald project in several neighborhoods throughout the city. Housing advocates say failure of Duggan’s marquee project could sink hopes for other neighborhoods.

“I’m concerned,” said Barry Randolph, pastor at Church of the Messiah in an east side Islandview neighborhood, where the city on Nov. 19 announced an 80-unit housing revitalization project.

“If that project (in Fitzgerald) does not succeed, what does that say about future projects for affordable housing in Detroit? That’s a city-led project,” he said. “Are they really trying to pull it off?”

Delays are common in all development, especially in blighted areas. And Detroit has never before attempted a neighborhood revitalization project the size and scope of Fitzgerald, said Arthur Jemison, the city’s housing director.

Others say Duggan, who announced the Fitzgerald plan during an election year, may have over-promised what he could deliver – but neighborhood revitalization efforts with realistic goals will march on.

“The wrong message is this means neighborhoods cannot redevelop,” said Donna Givens, president and CEO of Eastside Community Network, a community development nonprofit.

“Do I believe Fitzgerald will come back? Yes,” she said. “Do I believe people were starry-eyed and overambitious? Yes.”

Reward for longtime residents

Located in Northwest Detroit, the Fitzgerald neighborhood is nestled between the University of Detroit Mercy and Marygrove College and is just south of the now-bustling Livernois/Six Mile commercial district.

About 600 families live in the quarter-mile area that is burdened with more than 100 vacant houses, dozens of empty storefronts and more than 200 vacant lots, according to the city.

The project represents a bold gambit for Detroit: It would turn vacant properties – long viewed as a scourge on the city’s property values and reputation – into an asset to rebuild a neighborhood.

The plan includes rehabbing all of the city-owned property including 100 vacant houses - half will be sold and half leased - building a 2-acre park, a bike path connecting to nearby colleges and repurposing 192 vacant lots.

Doing so would reward residents who stayed in neighborhoods despite deterioration over the years, city officials say.

“That is top of mind,” Jemison, the city’s housing director, told Bridge Magazine.

He said the project is behind schedule in part because the Detroit Land Bank, the government agency that owns tens of thousands of vacant city homes, took months to transfer clear titles to the properties, Jemison said.

He said he’s confident initial hurdles have been cleared and the project can meet its goal of rehabbing 97 homes in two years. Other neighborhood projects won’t be affected, he said.

“We think we’re going to be able to work in neighborhoods to come up with local solutions that respond to specific things those neighbors are asking for,” he said.

There is progress. The Ella Fitzgerald Park opened this summer offering a oasis that stands in contrast to the blight around it. Neighbors helped tile the art wall and it has all new basketball courts, barbecue grills, tables and a walking path.

Most of the lots also are cleared of overgrowth. And a community garden began, but its food is seldom harvested because neighbors worry the soil could be contaminated, said Stephanie Harbin, president of the San Juan Block Club in Fitzgerald.

The delays have convinced some Fitzgerald neighbors the 100 house rehabs will never happen, but others refuse to give up, Harbin said.

“This is real. It’s not for play,” she told the group touring through Fitzgerald. “It’s really happening.”

Too expensive for Fitzgerald?

Others question whether Detroit’s real-estate market can support the project.

The city took CityLab conference visitors past one of the first three homes to be completed. It was rehabbed for about $120,000 but sold for $55,000, according to the city. Federal funds and donations from philanthropy helped offset the costs to keep the prices affordable, said Alexa Bush, a design director for the city’s planning and development department.

The first three houses sold within two weeks on the market. But other homes in the project are expected to cost $90,000 or more in a historically blighted area six miles from downtown.

Other homes now on the market in the neighborhood list for $20,000 to $70,000, according to real-estate listings.

“There are those of us who question Fitzgerald being selected for this. The market is not there yet,” said Givens, the east side community leader.

Givens said the 2020 completion date for the 100 home rehabs is too ambitious.

“There are those of us who question selecting (a developer) who never developed 100 houses to do that,” she said. “I don’t want to believe anybody set them up to fail. I don’t think that the project was designed effectively.”

The developer is Fitz Forward, a joint venture between Century Partners, a firm that had previously redeveloped two dozen house in Detroit, and The Platform, a firm involved in a mix of projects citywide.

David Alade, co-founder at Century Partners, said the Fitzgerald project is going through typical delays for a complicated project.

“I feel actually very good about selling or leasing all 100 of these houses,” he said. “ I think there is strong demand for affordably priced homes.”

Margaret Dewar, professor of urban planning at the University of Michigan, recently drove around the Fitzgerald area and came to a familiar conclusion about the 100-house rehab timeline.

“Oh, that’s a heavy lift,” she said.

Another issue is the economy, Dewer said.

“It’s good they’re moving ahead,” she said. “What they want to hope for is that there’s not another recession that would impact demand.”

“They don’t need anything to lower demand.”

Dorian Harvey, president of the Detroit Association of Realtors and self-described cheerleader for the city, said the biggest hurdle is Detroiters’ own doubt about the city’s worth.

“You must address the needs of local consumer first and then market to out-of-market consumers looking for affordable priced homes,” he said.

“Whether its 600 houses or 50, this is a time for risk taking. We’re so far behind and long overdue” for revitalization, he said.

All eyes on Fitzgerald

Fitzgerald is Duggan’s first foray into neighborhood revitalization – and the highest-profile effort of the Strategic Neighborhood Fund, a combined effort by the city, JP Morgan Chase and several foundations.

Detroit already has raised $42 million for improvements in Fitzgerald, Southwest Detroit along the Vernor Highway and the Islandview and Villages area on the east side.

Earlier this year, the city announced it planned to raise a total of $130 million for seven other neighborhoods: Jefferson Chalmers, Rosa Parks/Clairmount, East Warren/Cadieux, Gratiot/Seven Mile, Campau/Banglatown, Russell Woods/Nardin Park and Warrendale/Cody Rouge.

Revitalization of those neighborhoods is possible even if Fitzgerald doesn’t hit all its goals, said Sarida Scott, executive director of Community Development Advocates of Detroit.

But what will it take?

The advice and involvement of community development organizations that have over the years built small numbers of housing units; attracting and sustaining new resident-owned businesses; employment opportunities’, and homebuyer assistance funding.

And patience, Scott said.

“This level of investment hasn’t happened like this in decades that’s why a lot of this is learning as we go,” Scott said. “I think (delays) already did affect community perception. People in other neighborhoods are watching. I think it did have some ripple effects and I think that influenced how the city is moving in neighborhoods now.”

Samana Sheik contributed to this report.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!