Report: Michigan’s most vulnerable students have limited learning options during the pandemic

The students who need in-person instruction the most are among the least likely to get it, new Michigan data shows.

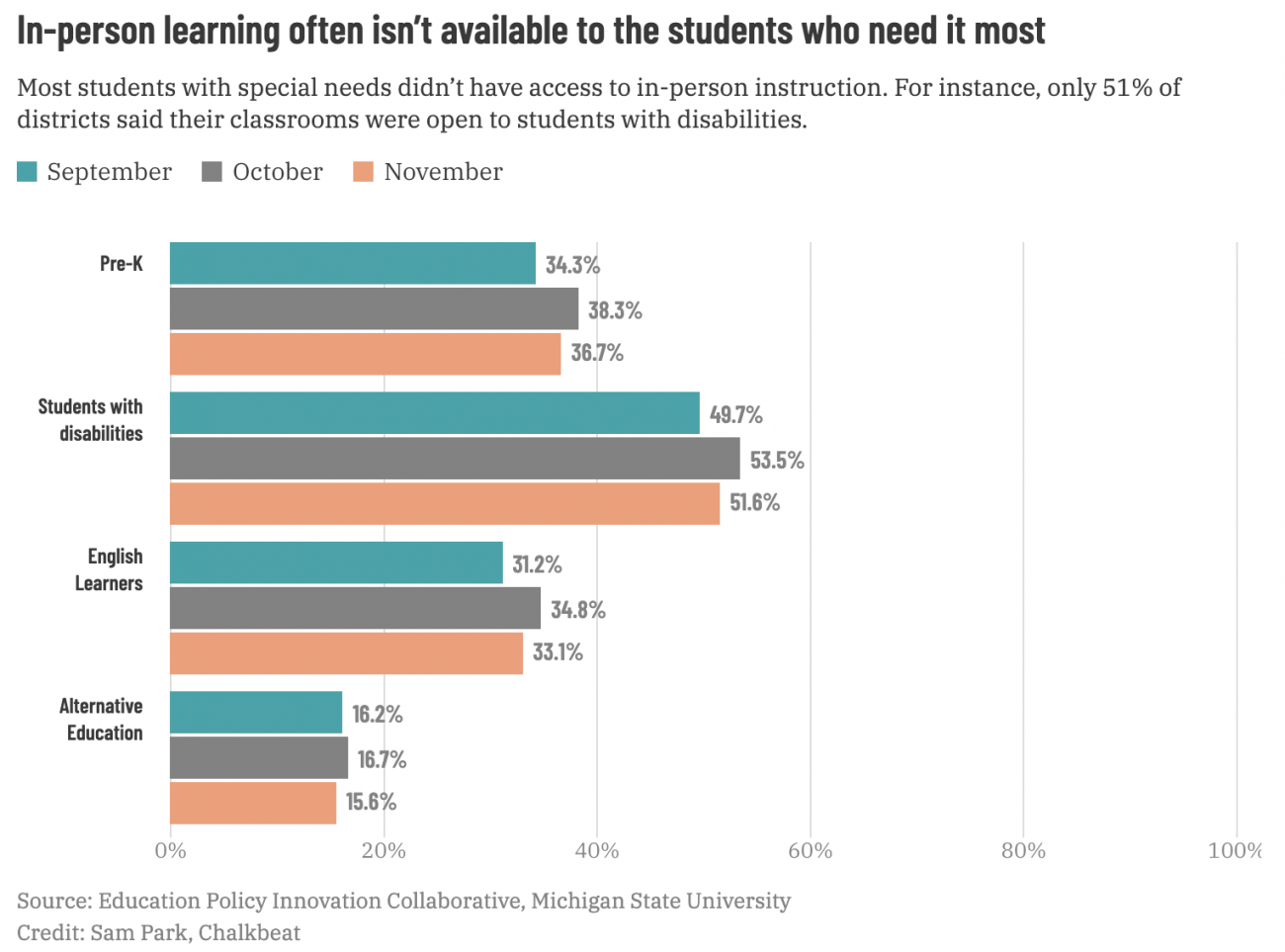

Education leaders in the state have insisted since the beginning of the pandemic that virtual instruction simply can’t meet the needs of thousands of students — notably young readers, English learners, students with special needs, and students from low-income families who may not have the resources required to learn from home.

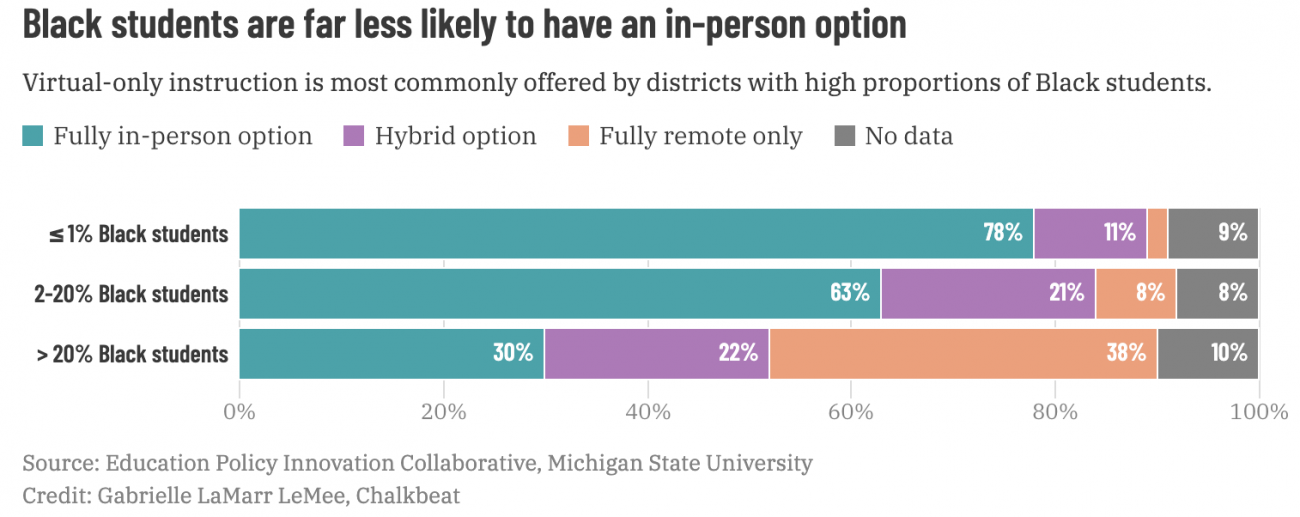

But this fall, as the pandemic raged, many of those students didn’t have the option to learn in person. Students from low-income families were seven times less likely to have an in-person schooling option than their wealthier peers, and Black students faced a similar disparity. Only half of districts reported opening their classrooms to children with special needs.

“These numbers devastate me,” said Katharine Strunk, a professor at Michigan State University who helped collect and analyze the data. “Even if parents don’t choose the option to be in person, it’s hard for me to explain why we think it’s okay to give wealthier and whiter families the choice to be in person and not give less wealthy and Black students” that choice.

Educators generally agree that in-person instruction is ideal for most students under normal circumstances. Eight months into the pandemic, survey data suggests that online instruction remains a major challenge for families, even though many say it has gone better this fall than in the spring. In Michigan, districts estimated that students received live instruction from a teacher less than half the time they were online.

The new data, which was self-reported by districts in recent weeks and released Thursday, offers the clearest picture to date of districts’ approaches to pandemic education. The numbers were published by the Michigan Department of Education in partnership with researchers at Michigan State.

The data is not fully up-to-date. New COVID-19 cases have reached record highs in Michigan and nationwide since the last data was collected from districts on November 11. Since then, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer ordered all high schools and colleges to stop in-person instruction.

Strunk cautioned that self-reported data is prone to errors. What’s more, out of 833 districts and charter schools, 70 didn’t submit data for November, and over two dozen didn’t submit data for September and October.

Still, the numbers offer an unparalleled glimpse of students’ experience during the pandemic — and point to grave inequities in Michigan’s approach to the pandemic.

“We’re going to have kids receiving a lower quality education this year, and they were already disadvantaged by the system,” Strunk said. “How are we going to make this up next year?”

Here are a few key takeaways from the data:

The pandemic is hurting the most vulnerable at school, too

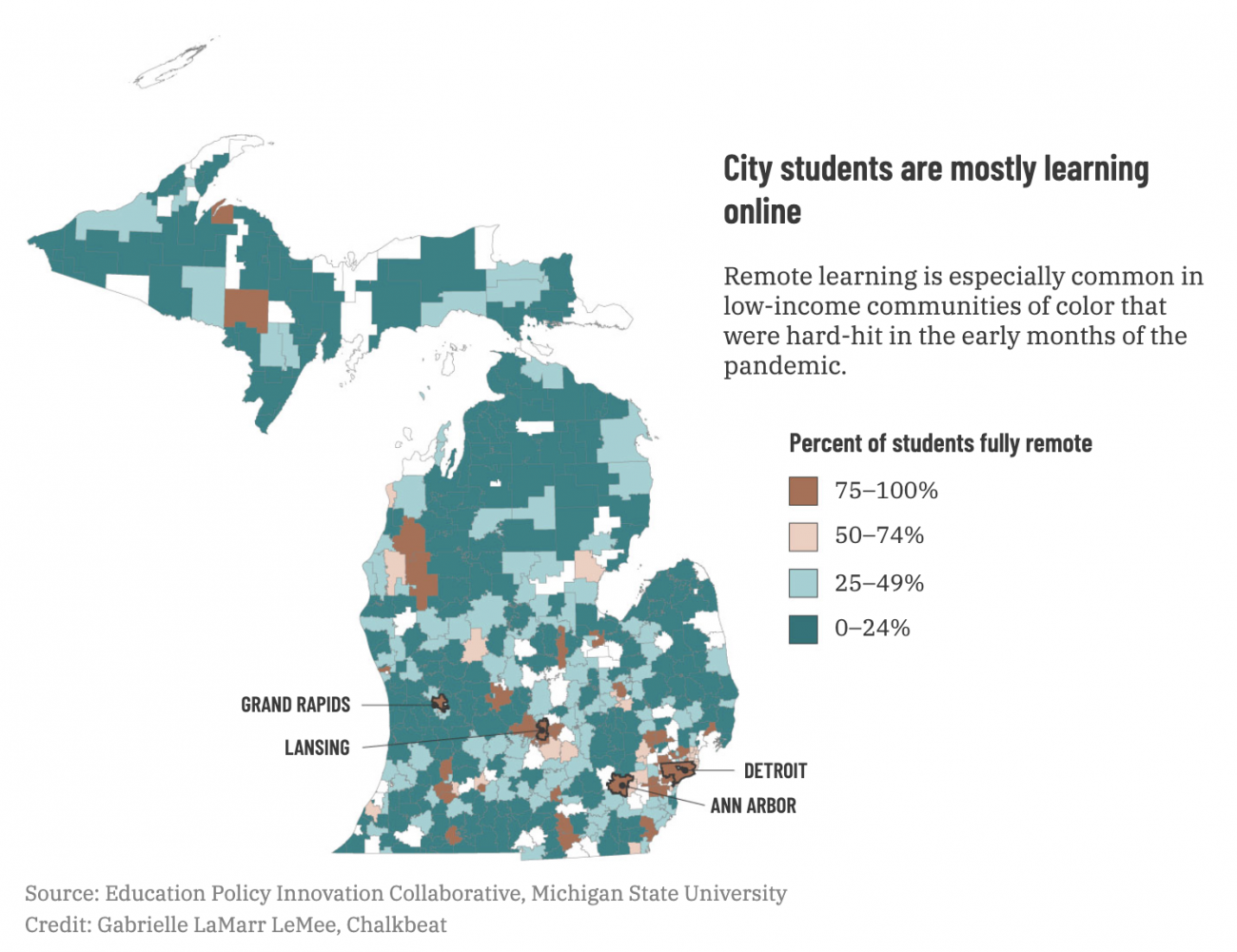

In the early days of the pandemic in Michigan, cities were especially hard-hit.

While the coronavirus has now spread to every corner of the state, students in urban areas are still far less likely to be learning in-person than their peers across the state. These students tend to be people of color who come from low-income families, exacerbating educational inequities that were entrenched in Michigan even before the pandemic.

The politicization of the public health crisis has likely fueled the divide — national studies have suggested that a region’s political affiliation is linked to school reopening decisions.

Fear of the coronavirus also reduced the number of students learning in person, even when they had that option. In Detroit, where more than 1,500 people have died of the virus, the vast majority of parents who had the choice to send their child to a classroom chose to stick with remote learning.

Even when parents have the option to send their children to school in person, many choose online instruction.

Across the state, roughly 15% of students attended a district that was only offering virtual learning in November.

Yet the proportion of students who were actually learning online was between 33% and 50%.

Few districts are offering additional in-person services to students who need them most

Stephanie Onyx’s two children normally receive full-time help at school. Both have multiple severe special needs, and their schools in Troy provide numerous therapies to help them develop, some of which can only be done in person.

When Troy closed its classrooms this fall, Onyx, a single parent, was left to meet all of her children’s needs by herself.

Just half of schools in Michigan have provided an in-person option to families like this, whose special needs make in-person learning especially important.

Even fewer are providing an in-person option to English learners or prekindergarten students.

Younger students aren’t getting the extra attention they need

The pandemic has been especially hard on families with young children, who tend to have trouble working independently and sitting in front of screens. Experts agree that the early years of education, when students learn fundamental skills such as reading, are especially important.

Yet across Michigan, younger students haven’t been given more opportunities for in-person learning.

Younger students also didn’t get much additional live instruction — when they are interacting with their teacher in real time, typically by videoconference — compared with their older peers.

Kindergartners learning online received live instruction between 32% and 50% of the time. The proportion of live instruction was almost identical for high school seniors — between 30% and 48%.

Majority Black and low-income districts are less likely to offer in-person learning

Districts with a high proportion of Black students were far less likely to offer in-person instruction.

Remote instruction was the only option in November at 38% of districts which enrolled 20% Black students or more. (African-Americans make up 18% of all Michigan students.)

By contrast, 78% of districts with almost no Black students planned to offer in-person learning in November.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!