‘It’s been hell.’ 1 house, 5 kids, and a pandemic struggle to learn at home

In a log home on a dirt road in Montcalm County, school is supposed to be in session.

Ten-year-olds Reese and cousin Lukas sit at desks in a hallway trying to sign in to the same Tri County Area Schools fourth-grade classroom on their laptops. Lukas’ connection works, while the connection for Reese, sitting just feet away, is frozen.

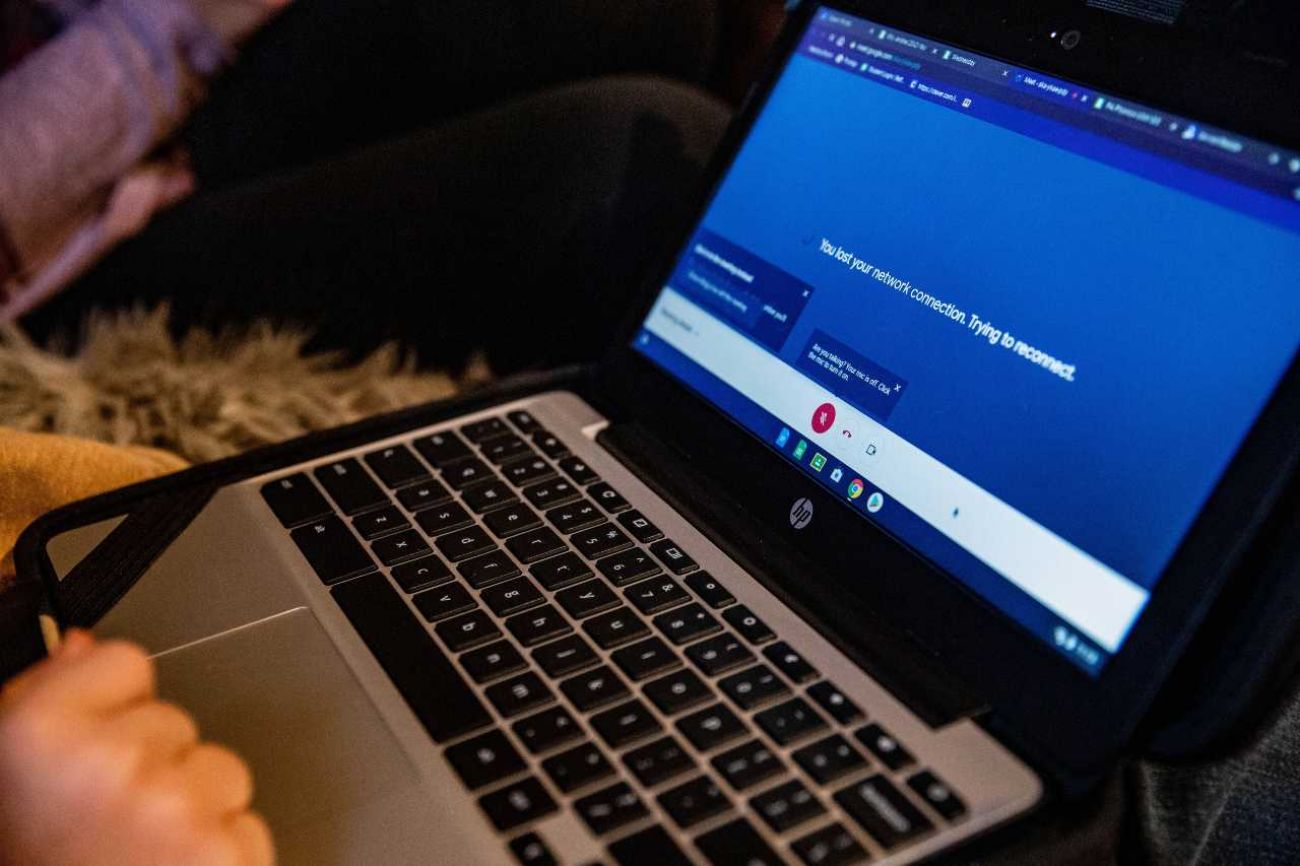

Kensley has managed to sign on to her sixth-grade class, and she scribbles notes as the teacher talks, while on a couch in the living room, 8-year-old Karlyn’s computer disconnects from her virtual second-grade classroom while her teacher is talking.

Thousands fled Michigan schools in fall. Will COVID home-schoolers come back?

Some Michigan schools will stay remote until January amid COVID

And in the kitchen, 5-year-old Jameson lies down on a bench and covers his eyes, saying he doesn't want to work on his computer any more today.

Running between the children is Sarah Langell, mom to four remote-learning students and aunt to another who comes to the home with his 3-year-old brother while their own mother is at work. Sarah is a hair stylist by profession, but for the last three weeks, she’s spent her days trying to be a computer tech and teaching assistant.

It’s not going well.

“It’s been hell,” said Langell.

Across Michigan, children are learning at home in numbers not seen since the spring, when Gov. Gretchen Whitmer ordered all public and private K-12 schools to switch to remote learning to try to stem the spread of the coronavirus. All high school buildings are closed through at least Tuesday, under a three-week closure order from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. That order might be extended in coming days, and even if it isn’t, many districts have chosen to go fully remote until at least January because of high COVID case numbers and a shortage of substitute teachers to fill the classrooms of teachers now in quarantine.

Even before the rash of building closures in recent weeks, between a third and a half of all Michigan K-12 students were taking all of their classes from home.

Online learning is a particularly fraught affair in rural Michigan, where access to high-speed Internet is limited. Across the state, 3 out of 4 school-age children have high-speed Internet in their homes, with Michigan ranking 33rd among the states. In the northern Lower Peninsula of Michigan where the Langells live, just 63 percent have easy access to broadband, according to research by Public Policy Associates, a Lansing-based public policy firm.

“The pandemic has really shone a light on the issue of broadband access disparities,” said Dan Quinn, director of education policy for Public Policy Associates.

Not-so-hotspots

Tri County Area Schools, a rural district of about 1,800 students, gave families the choice of in-person instruction or remote learning this fall. The Langell family chose to put their four kids on the bus each morning to attend classes in school buildings.

That ended Nov. 19, when the MDHHS ordered high schools closed for three weeks, and Tri County officials made the decision, at the recommendation of the local health department, to close K-8 classrooms also.

Tri County Superintendent Allen Cumings said staff members handed out Verizon WiFi hotspots to 250 families in the district who did not have WiFi at home. The Lanells, who live in a rural area without access to broadband, received one of the devices, which provides WiFi through a cellphone signal.

The device is a good stopgap for students without broadband access, but it doesn’t have the bandwidth for five students to live-stream classes on school-issued Chromebooks at the same time, said Public Policy Associates’ Quinn.

The five children move from kitchen to living room to bedrooms during school days, and Langell trails behind with the hotspot, trying to triangulate a location for the device where all can get a signal strong enough to connect with their teachers.

“I feel very fortunate, because our district has provided hotspots, but there’s been so many issues,” Langell said. “I feel like we’re on overload.”

A typical homebound school day starts later than in-person school days (“They don’t have to get up at 6:30, eat and get to the bus.”) but lasts longer, as kids wait their turn to get WiFi access.

“It’s not unusual for my fourth-grader to be working past 5 p.m.,” Langell said.

Sometimes kids can’t connect to their classrooms at all; other times, the signal drops in mid-lesson. Langell has seen the faces of her children’s classmates pop onto screens, then disappear minutes later.

“I think, ‘at least we’re not the only ones’” having problems.” Langell said.

Tri County Superintendent Cumings said the pandemic-induced changes in school schedules have been tough on students, parents and teachers alike.

“We’re trying to do the best we can to manage it,” Cumings said. “We’re forced to make these decisions as schools, and parents ... are forced to be teachers. It is stressful.”

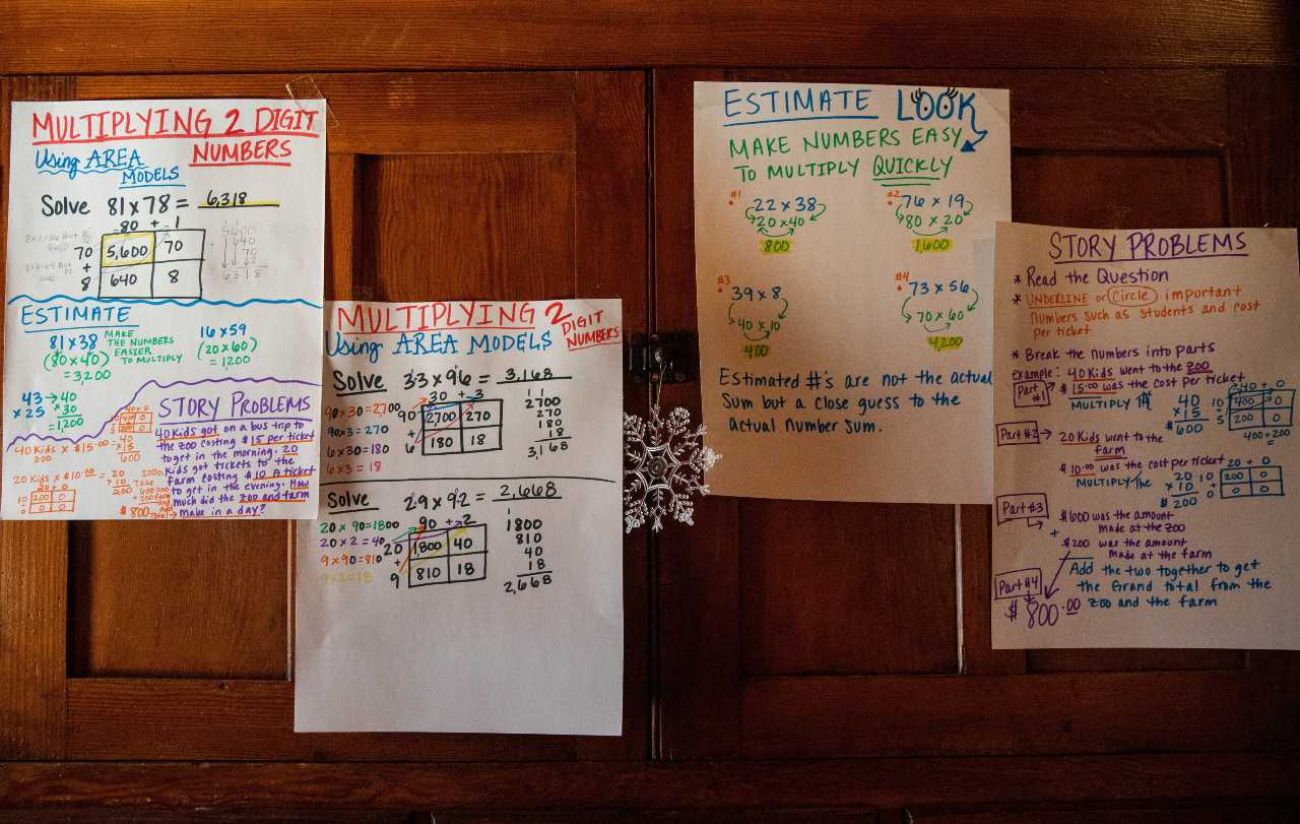

Langell sometimes cries when talking about her struggles to help her kids. She doesn’t know how to fix computer glitches. She spends so much time helping her younger children, she’s left sixth-grader Kensley on her own. “I have to assume she’s keeping up,” she said.

At the end of one frustrating day, Langell wrote an email to the second-grade teacher of daughter Karlyn expressing her concern that her kids weren’t keeping up. “I feel as though I’m failing them,” Karlyn wrote.

“You can’t feel as much of a failure as I do,” the teacher wrote back. “I feel like I’m building the plane as I fly it, and parts keep falling off!”

On Thursday, Langell told Bridge Michigan she hoped classes would resume the following week. By the next day, she’d received an email from Tri County schools announcing that school buildings would be closed through at least Jan. 11.

All school districts in Montcalm County are now fully remote until January.

Superintendent Cumings told Bridge that with cases on the rise in Montcalm County, and the trouble the district has keeping up with contact tracing in its classrooms, it was difficult to justify reopening for the two weeks before the winter break.

Langell said she doesn’t blame the schools. She knows they are in the same no-win situation as her family, caught between education and safety in the worst pandemic in a century.

“There are blessings in it. I’m thankful to have time with them. But no one’s winning,” Langell said.

“I feel the teachers are doing the best they can, and they’re trying to implement [online learning] as best they can. But I feel like [my children] are not getting the education they need. And that’s frustrating.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!