Video tablets are lowering suicides, raising treatment for rural veterans

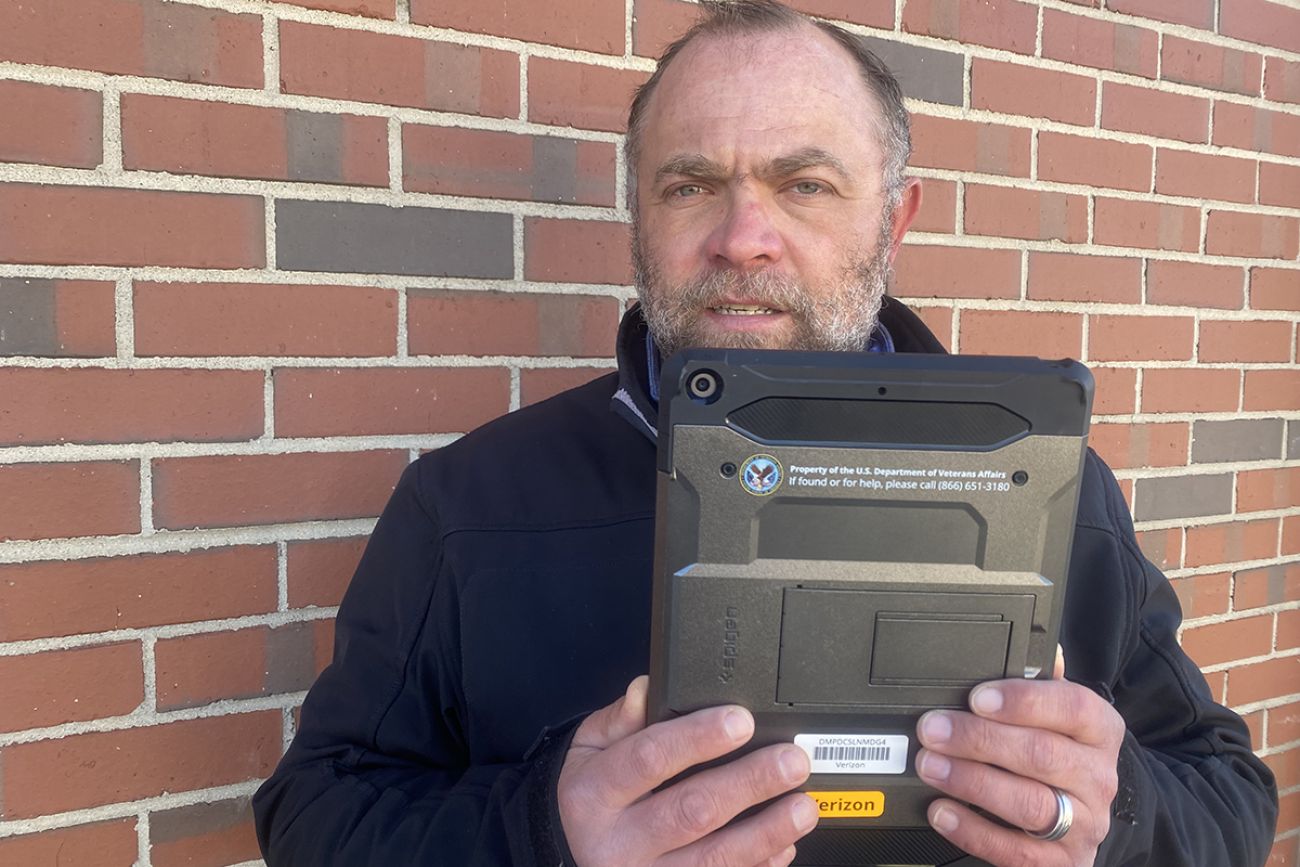

Over the past couple years, a gray-and-black computer tablet has become an indispensable ally to U.S. Air Force veteran Andrew Labadie.

From his home in rural Branch County just north of the Indiana border, Labadie can tap into a web of mental health specialists: counselors, psychologists, recreational therapists. Or he just might take his tablet out in a nearby stand of trees.

“I would have been the last person to say I would rather have a tablet instead of personal care,” said Lababie, 39, who said he has dealt with post traumatic stress disorder, depression and anger management issues following his departure from the U.S. Air Force in 2007.

Related:

- Detroit hospital stops admitting patients to control rare fungus outbreak

- Michigan’s Medicaid ballooned during COVID. It’s about to be pared back.

- Smokestacks and forgotten residents: Dearborn opens new health department

“But this tablet has been crucial to my life,” he told Bridge Michigan.

“I can go take a session for my mental health out in the woods. I feel like I’ve been able to dig deeper into some of the things I deal with.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic forced the shutdown of in-person mental health services across Michigan in March 2020, U.S. Veterans Affairs officials say that remote care has become a critical alternative to the traditional model of face-to-face therapy. That’s especially true in rural Michigan, where mental health services were scarce even before the pandemic.

“We’ve had a lot of positive feedback from veterans,” said Russell Bell, a VA social worker based at the Battle Creek VA Medical Center.

“In the beginning, it was a new way of treatment. There was some resistance. But as they learned it offered opportunities they didn’t have before, a lot of veterans were happy they didn’t have to drive an hour-and-a-half for counseling.”

A recent national study of more than 13,000 rural veterans who received video-enabled tablets through the VA showed positive results. These veterans received more mental health care than other veterans, more remote or in-person psychotherapy, showed less suicidal behavior and had fewer emergency room visits.

The results, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, come amidst accumulating evidence that veterans ─ especially those in rural areas ─ are at greater risk of suicide. U.S. veterans are 1.5 times more likely to die from suicide than non-veterans. In Michigan, veterans were 1.65 times more likely to die from suicide in 2019 than the overall population. And Michigan veterans ages 18 to 34 were nearly three times more likely to die from suicide than the overall population within this age group.

And the risk for veteran suicide may be greatest in rural areas, as sparsely populated counties in the northeastern half of the Lower Peninsula and eastern half of the Upper Peninsula have the highest suicide rates in Michigan.

Experts attribute these grim numbers to an array of factors, including the social isolation of rural areas, economic distress, greater access to guns and a long-standing shortage of mental health workers.

In 2018, 10 rural counties in Michigan had no psychologist or psychiatrist, while 15 rural counties had no psychiatrist.

“We certainly need to close the gap in mental health care in rural Michigan,” said Kevin Fischer, executive director of the Michigan chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“We know the need for mental health care has only gotten greater through the pandemic. Those who had mental health diagnoses have gotten worse, whether it was for depression or anxiety.”

Indeed, a February 2021 poll by KFF, a national health research organization, found that four in 10 U.S. adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder during the pandemic ─ compared to one in 10 adults who reported those symptoms before the pandemic.

Fischer said the need for mental health care may be especially acute for isolated Michigan veterans reluctant to share with others the psychological pain they are enduring.

“I talk a lot about destigmatizing mental illness ─ it’s a huge problem among veterans, because in the military you are trained to ignore physical injury,” Fischer said. “They are not going to admit a mental health issue. It’s harder for them.”

State officials acknowledge that the need to expand mental health services in rural Michigan stretches back years, whether for veterans or the general population.

“We have been aware there have been gaps in rural Michigan,” Dr. Debra Pinals, medical director for behavioral health for the Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services, told Bridge. “It’s hard to recruit and retain professional staff.”

She added: “There’s no one answer that can solve all these issues.”

Though Michigan has tried, including by giving financial incentives for medical workers to move to rural areas. Pinals pointed to the MDHHS student loan repayment program that offers physicians, nurses and an array of mental health specialists up to $300,000 in loan repayment if they commit to provide services in underserved areas of Michigan.

She also noted that many Michigan military service members completed their duty as members of the National Guard or Reserve. They are not technically considered veterans — and are for the most part not eligible for VA benefits — unless they were called to active duty.

A state planning document notes many of these former Guard and Reserve members “frequently go unidentified for mental health and substance use disorders. They believe that help is not available.”

To reach former service members, as well as active duty veterans, MDHHS in 2017 funded a network of workers familiar with the mental health system to connect them to mental health resources, as it estimated in 2020 that it had helped about 3,000 such individuals.

The VA, responding to the barriers to mental health care in rural areas, moved to expand remote mental health services even before the pandemic as it began sending tablets to veterans about in 2016. In many cases, these were veterans with no other way to access remote care.

The JAMA study underlined the value to veteran well being of these tablets, as it found that veterans who used tablets were 36 percent less likely to have a suicide-related emergency room visit and had a 22 percent reduction in suicidal behavior, compared to other veterans. Currently, the VA said, more than 100,000 tablets are in circulation across the country.

In the Upper Peninsula, VA psychologist Christy Girard said that while these tablets are a boon to some veterans, remote care is still hard to find in wide swaths of the peninsula where speedy digital connections are rare to non-existent.

“It’s a real challenge up here when we try to get people connected,” Girard told Bridge. “There’s big areas of the U.P. where the internet just isn’t a reliable option.”

That’s reflected in a map of high-speed broadband that shows much of the U.P. without such access, as well as areas across the northern half of the Lower Peninsula.

According to VA records, about 27 percent of some 4,000 veteran mental health patients in the U.P. had at least one video-connected mental health session in fiscal 2021, while just more than a third of mental health care to veterans was provided face-to-face.

And while some veterans warmed up to remote mental health sessions, Girard stressed that other veterans do better with in-person care. She sees a need for both options.

“Two years into the pandemic, people are just wanting to have the face-to-face connection again,” she said.

But in rural northern Kent County, U.S. Army veteran Jeff Cline told Bridge he’s happy to plug into remote mental health sessions just about whenever he wants. Cline said he’s dealing with an addiction to alcohol and post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) tied to his military service.

“I don’t feel like missing anything by not doing it face-to-face. If anything, I’m gaining, because I don’t have to do an hour round trip,” he said, referring to the drive from his home to VA mental health services in Grand Rapids.

Cline, 44, said he left the Army in 2018 after 20 years in the service, which included tours In Iraq in 2004 and 2008.

He said he was assigned to a civil affairs unit in Iraq, tasked with building relationships with the local populace. That didn’t mean his unit was immune to the roadside bombs and other forms of violence common to the Iraq War.

“There was a 19-year-old woman, private first class. She was driving the vehicle behind me when a (roadside bomb) went off. It decapitated her,” he told Bridge.

Back in Michigan after his discharge from the Army, Cline recalled, his PTSD could creep up on him like an ambush.

“I was at a Meijer store checkout line. All of a sudden, I felt warm and sweaty, labored breathing, and I literally passed out in the checkout line,” he said. “I’m pretty sure I knew nobody there was going to stab me, but something in my head told me I wasn’t going to be comfortable in that situation.”

Cline said he’s focused for now on beating his addiction to alcohol, before turning his full attention to PTSD. He’s found daily remote group sessions with other veterans grappling with similar addiction issues particularly helpful.

“They offer those at 9 a.m. and 10 a.m., and if I’m not doing anything else that day, I just might go (through remote connection) to both. It’s been really good. The peer support group is like you are getting an education in a group setting. You are learning about the cognitive reasons for the addiction and the PTSD.”

In the meantime, Labadie, the Branch County veteran, can be something of a one-man advertisement for his VA tablet.

“I think every VA staff member and veteran should have a tablet,” he said. “When you have a tablet, it’s almost like they are close to you.”

Labadie credits one of his therapists, former Battle Creek VA clinical psychologist Elizabeth Torgersen, with helping him sort through his mental health issues in their hour-long remote sessions. By contrast, Labadie found himself distracted during the drive to in-person counseling in Battle Creek, to the point where he felt like his state of mind sabotaged the sessions.

“It was the anticipation, the drive, and all that forward thinking, because my mind starts racing. It really poisoned my thinking.”

The pair maintained their therapeutic connection, even after Torgersen moved to Wisconsin in 2020 to take another position with the VA.

Torgersen told Bridge that remote mental-health care is by no means for every veteran. But she said that for some, it can be a lifeline.

“In Andy’s case, he can drive his vehicle out in the woods and have a session, where he feels most comfortable,” she said. “We can literally meet the veterans where they are physically and emotionally.”

For Labadie, that has meant significant steps forward.

“Dr. Torgersen has really helped me open up with the virtual sessions, in really being comfortable with where I’m at. It’s brought light to the situation and helped me fight through the clutter.

“It’s like, everything is OK.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!