In Wayne, passing the hat for a fire hose

WAYNE – One recent Saturday evening, residents from the city of Wayne gathered at a local bowling alley for a fundraiser. It wasn’t to support a local Girl Scout troop. Or to send high school trombone players to band camp. Those are luxuries this small city west of Detroit can no longer afford.

Instead, residents converged on the Wayne Bowl to help the fire department pay for working fire hoses. And saws. And ropes. There is simply no money left in the budget for these bare essentials. Weeks earlier, local businesses and ordinary residents held another fund drive to replace the fire department’s ancient jaws of life, which was too feeble to pierce modern cars to free accident victims.

On this night, residents would be bowling for fire hoses.

“Our city is cut to the absolute minimum,” Wayne-Westland Fire Capt. Fred Gilstorff said of the need for the bowling event. “There’s no more fat to be trimmed.”

With city revenue cut in half since 2008, the burden on residents is about to get even steeper. In August, the city’s blue-collar voters will be asked to approve an annual millage of 14 mills, which the city said it must pass to join a multi-city authority to share the costs of public safety.

“It’s going to be a heavy lift,” conceded City Manager Lisa Nocerini, as she talked above the din of falling pins at the Wayne Bowl. “But there’s no way we can get the necessary revenue without this millage. We can’t keep cutting our way out of this.”

Much of the blame for lost revenue falls on the usual trio of suspects: a sharp drop in state revenue sharing (Wayne has lost $7.8 million since 2002 ); a state law that limits Wayne’s ability to recoup property tax revenue after the 2008 recession, and legacy costs of city retirees.

Making matters worse, city leaders say, were economic setbacks involving its largest employer, Ford Motors, which operates two plants in Wayne. First, there was a devastating ruling by the Michigan Tax Tribunal a few years back that slashed property taxes Ford must pay the city. In the years since, the city has scrambled to avoid having to outsource its police and fire services. Then last July, Ford announced it was ending production of two slow-selling models at its Michigan Assembly Plant, after an earlier announced layoff of 700 workers.

The annual budget in this city of roughly 17,000 has dropped from $23 million (adjusted for inflation) in 2006 to $15.4 million, said John Rhaesa, a city council member. The sharp drop in revenue has meant a flood of shorter-term cost cutting.

Wayne went from having 171 city employees in 2006 to 76 a decade later, with other workers taking pay cuts or reductions to part-time status, which in turn prompted other workers to seek better job security elsewhere. The fire department has shrunk from 24 employees to 12. Building engineers help answer office phones. Police work 12-hour shifts after seeing their ranks dwindle from 42 officers in 2005 to 23 today.

And it seems like nearly every city worker has developed a side career as a grant writer in a bid to find money to fill budget gaps.

Mayor Susan Rowe has not been immune from difficult budget decisions. Back in 2009, when she served on city council, Rowe said she voted to reduce funding for the building department, a vote that forced her husband, Ed, into part-time status.

Through all the challenges, people interviewed at the bowling event said, the city’s police and fire departments have made it a point of pride to maintain a high level of performance. Bernadette Brock, who helped organize the fundraiser, said that a week earlier emergency responders from the fire department arrived at her house within five minutes when she found her mother unconscious from a stroke. She recalled that one responder, who she nodded to across the room, had stopped to reassure Brock before taking her mother away.

“There’s nothing I wouldn’t do for these guys,” she said.

The question, though, is why Brock has to. Cities in other states don’t typically resort to bake sales to buy public safety equipment. The can-do attitude of volunteers and donors in Wayne is an example of the resiliency of Michigan cities, but also illustrates how close they are tiptoeing toward a financial cliff.

Rowe, the mayor, said that if she could wave a wand over Lansing she would ask lawmakers to reconsider the state’s approach to funding schools and collecting property taxes.

“State representatives sometimes come in here and I say to them, ‘You used to sit where I’m sitting,’” she said of her local post. “‘What happened when you went to state government that you forgot what it was like to sit in my seat?’”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Unable to afford basic equipment, the Wayne Westland Fire Department has resorted to community fundraisers, a model that is working for the moment but is unsustainable over time. (Bridge Photo by David Zeman)

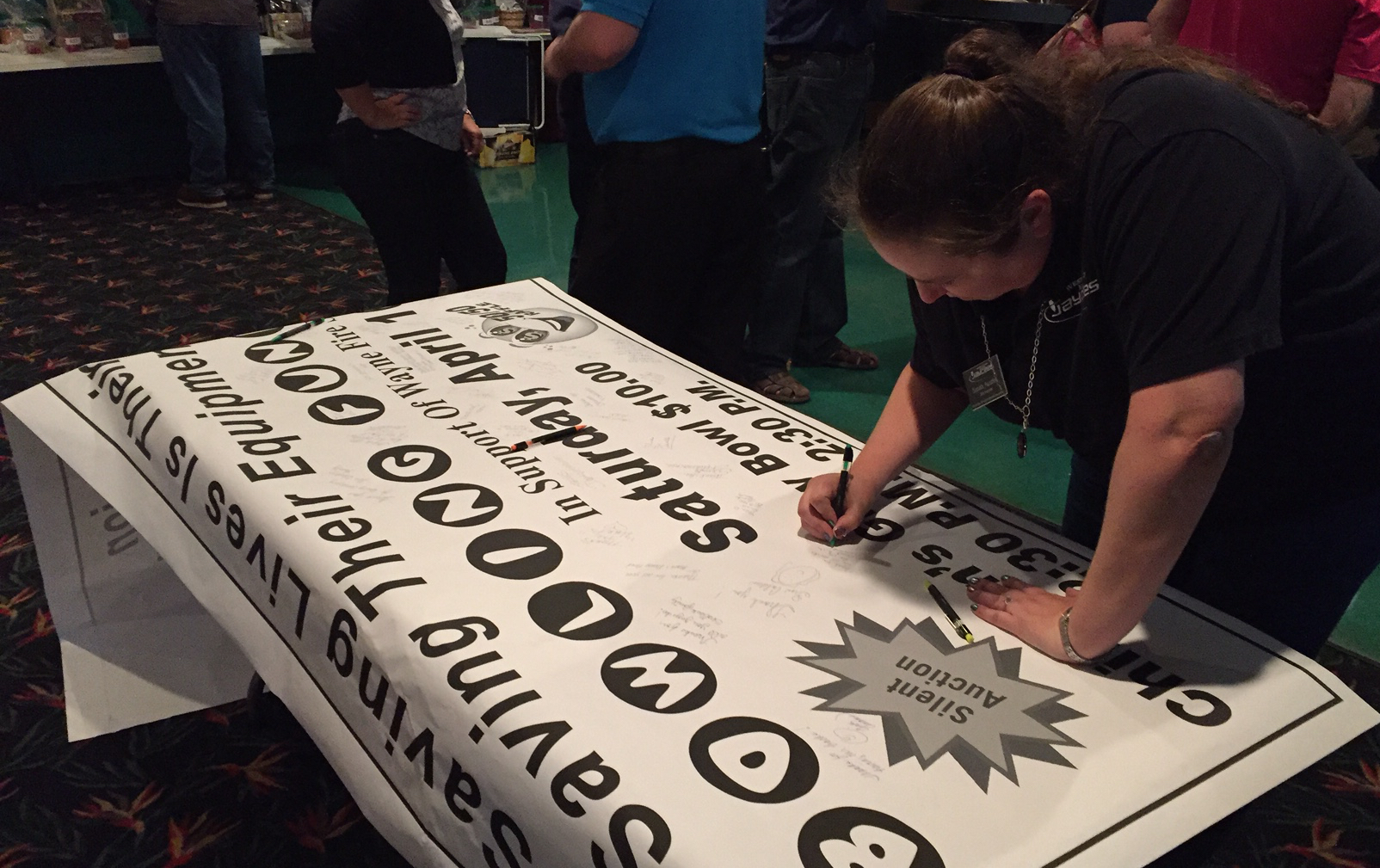

Unable to afford basic equipment, the Wayne Westland Fire Department has resorted to community fundraisers, a model that is working for the moment but is unsustainable over time. (Bridge Photo by David Zeman) A donor writes well wishes on a fundraising sign for fire equipment at a Wayne bowling alley. (Bridge photo by David Zeman)

A donor writes well wishes on a fundraising sign for fire equipment at a Wayne bowling alley. (Bridge photo by David Zeman) On this night, volunteers are raising money for fire hoses; recently, it was for a new jaws of life. The city budget in Wayne no longer has room for basic public safety equipment. (Bridge photo by David Zeman)

On this night, volunteers are raising money for fire hoses; recently, it was for a new jaws of life. The city budget in Wayne no longer has room for basic public safety equipment. (Bridge photo by David Zeman)