Studies: Betsy DeVos’ Let MI Kids Learn may help some, but promises overstated

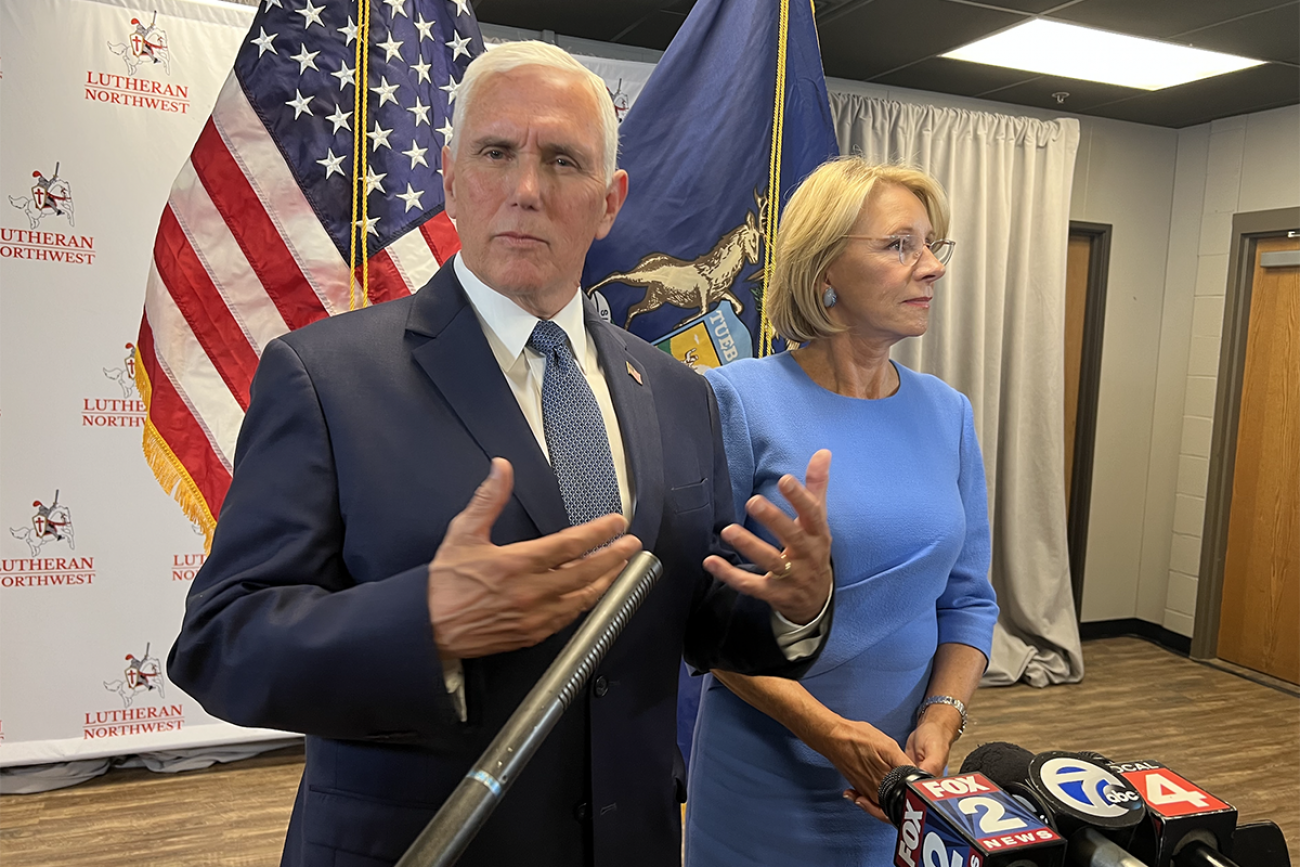

LANSING — Addressing hundreds at Lutheran Northwest High School in Rochester Hills in mid-May, former U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos made an ambitious promise: a school voucher-like program she is pushing in Michigan would empower “hundreds of thousands of children” to choose their education.

Backers like DeVos of the Let MI Kids Learn petition drive want to establish a program in Michigan that allows donors to contribute to a private scholarship fund and then receive tax credits that would be capped at $500 million total.

Parents of lower-income students in public or private schools could tap into the funds for school-related expenses. This year, that would amount to up to almost $8,000 per pupil for private school students or $1,100 for public school students.

Related:

- Betsy DeVos backs Michigan petitions for voucher-like school choice program

- Michigan educators to campaign against Betsy DeVos-backed petition

- 2022 Michigan petition drives tracker: What to know about election proposals

The idea is not new: At least 23 states established similar tax credit scholarship programs over the past 15 years.

Proponents say the programs boost student performance and give parents more control over their children’s education. Critics argue they could undermine public school funding and don’t improve academics.

The truth is somewhere in between. Bridge Michigan reviewed more than a dozen studies from other states and found that the programs have been linked to some academic improvements and better college access — and, despite fears, have not drained tax coffers.

But critics say the research is mixed at best and often funded by boosters of school choice programs and oversimplifies the impact of scholarship programs. Scholars say there are many factors in student performance, and the lack of consistent standardized tests between public and private schools makes comparisons difficult.

“The only way you could possibly know about whether this works is to have some reporting requirements on the private schools, but even then it becomes difficult because … you have to have a system that tracks individual students over time,” said Douglas Harris, an economics professor at Tulane University and director of the National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice who served as an informal adviser to President Joe Biden’s administration.

Let MI Kids Learn spokesperson Fred Wszolek acknowledged research varies, but deemed the Michigan proposal “novel.” The ultimate metric, he said, should be “parental satisfaction.”

“(It’s like) arguing whether eggs are good for you,” Wszolek told Bridge. “It can’t always be measured statistically.”

Organizers on Wednesday indicated they will miss a Wednesday deadline to submit signatures to qualify for the November ballot. The group likely will continue gathering signatures, however, and hopes the Republican-led Legislature adopts the measure.

Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, though, already has vetoed similar legislation.

A statewide poll, released Tuesday, found that most respondents, 93 percent, had heard little or nothing of the proposal. Nearly two-thirds of respondents, 64 percent, opposed the petition after hearing four arguments against it, according to the survey of 600 statewide likely voters by EPIC-MRA.

The questions were leading — labeling the initiative a “scheme” to divert “desperately needed” money from public schools — and the survey was commissioned by a group that opposes the Let Mi Kids Learn petition. The survey had a margin of error of 4 percentage points.

The programs generally work like this: Taxpayers and businesses can contribute to a private scholarship fund and claim 50 percent to 100 percent of their donations as tax credits. In most states, third-party organizations distribute the scholarship money to students.

If the initiative becomes law in Michigan, the state would have one of the largest tax credit scholarship programs among states with similar options.

Only Florida would have a higher cap at $874 million.

Michigan would become one of only four states — along with Pennsylvania, Missouri and Montana — allowing parents of both public and private school students to use the scholarship to cover education expenses.

Michigan’s scholarships would go to families making no more than twice the level needed to qualify for free and reduced lunch. For this year, that's $102,676 for a family of four. The program would cap private tuition at 90 percent of Michigan’s minimum per-pupil funding amount, which is $8,700 this year.

If it passes, the measure could face a legal challenge in Michigan, where the state constitution bars the use of public dollars to “directly or indirectly aid or maintain” private education.

At least three other states — Kentucky, South Carolina and Massachusetts — have similar language in their constitutions. In Kentucky, a judge blocked a similar scholarship program enacted by the Legislature from taking effect, because the state constitution required voters’ approval for such programs. The case is on appeal.

Proponents of the Michigan initiative have argued the petition language is “well-crafted” and would survive any constitutional challenge.

“It is not the government sending money to a religious or faith-based school or any other school,” DeVos told reporters at the Rochester Hills event. “The reality is these funds are going to families to decide where to best send their children and find the right fit for them.”

Editor's note: This story was updated at 10:13 a.m. on June 1 to indicate that the measure likely will not qualify for the November ballot, but organizers hope the Legislature adopts it into law anyway. It was also updated to indicate students would be eligible for the program if they make 200 percent of the federal level to qualify for free and reduced lunch.

Assessing academic results

To get a sense of how vastly research on these programs differs, consider Florida.

Its Tax Credit Scholarship Program is the largest school choice program in the nation and one of the most intensively studied in the country. Some 85,000 of the state’s 2.8 million students, 3 percent, used the program during the 2021-2022 school year, according to EdChoice.

A 2017 study, funded by philanthropies that donate to school choice advocacy, concluded that participating in the program increased college enrollment rates by 15 percent. It compared 10,000 low-income students who received the scholarship from 2004 to 2010 and compared them with public school peers.

“We find clear evidence that participants in the nation’s largest private school choice programs were more likely to enroll in a community college than similar students who remained in public schools, with larger effects for students who spent more years in the program,” the report states.

But a separate study in 2020 of Florida students’ test scores concluded that many factors, beyond the scholarship program, affect performance. It also found that students who had been in the scholarship program and returned to public schools had “substantially lower test scores” than students with similar family incomes that weren’t in the program.

Another study, which assessed school choice, found that Florida low-income students and students with disabilities made larger gains than their peers nationwide from 2003 to 2019, according to an analysis of test scores of NAEP, the Nation’s Report Card.

But other studies nationwide found that tax credit scholarship programs and schools of choice had no impact on performance or hurt it.

A 2019 report that analyzed the District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship program for three years after students applied found that students using these scholarships were doing no better nor worse than similar students who weren’t using the scholarship program.

A 2018 study found math scores dropped in elementary and middle schoolers in Indiana during the first four years of the state’s Choice Scholarship Program. Another study in 2019 found “large negative effects” of Louisiana's school voucher program four years after implementation, particularly in math.

“On these voucher programs, what often happens is the results are mixed to slightly negative,” said Gary Miron, a Western Michigan University professor who has conducted dozens of studies on school choice programs and charter school reforms.

Scholars have also studied another form of school choice: charter schools.

The National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice compared communities with at least 10 percent charter school participation and communities with no charter participation.

Researchers found there was a 2 percent to 4 percent increase in high school graduation rates and higher scores in math and reading compared to non-charter communities The effects on math test scores were positive in every group of students regardless of race or income. The student data is from 1995 to 2016.

Results show the largest increase in math test scores in metropolitan areas compared to non-metropolitan areas and in middle schools compared to elementary schools.

Harris, the Tulane professor, and his co-author Feng Chen also found higher charter enrollment increases the likelihood that a traditional public school will be closed or be taken over. They did not find evidence to suggest that charter schools affect private school closures.

“We might also expect competition between schools when there are more charter schools – more schools means more competition for students and funding,” the report states.

“Indeed, we find that traditional public school performance rises with the charter enrollment share, though only slightly. This evidence may reflect correlation more than causation, but it is consistent with prior research.”

Who does the program benefit?

Studies have shown that school choice programs benefit more urban students than rural ones, who are surrounded by fewer private schools.

According to a 2020 report by the federally-funded Comprehensive Center Network, 53 percent of urban families have access to school choice programs compared to 32 percent of rural families.

Two-thirds of Montana’s private schools were located in the seven largest counties as of 2021, and more than half of its 56 counties did not have private schools, according to the Montana Budget and Policy Center, which is against the state’s tax credit scholarship program.

The programs primarily benefit students from low-income families, but they can be expanded to include those in the middle-class. Indiana’s program, for instance, was limited to families making 150 percent of the federal poverty level ($33,525 for a family of four) when it started in 2011, but eventually was expanded to three times that level by 2022 ($83,250 for the same family.)

Miron, the Western Michigan University scholar and critic of scholarship programs, said private schools would be under no obligation to participate in the program.

“The theory is … we have high-quality private schools that are catering to affluent families, it should be available to everybody,” Miron said. “You can’t force them to enroll these students, whereas in a charter school, a family could go to court and say, ‘My child is excluded.’”

Wszolek said the gap between urban and rural access to private education will “generally close over time” under the program as more private schools open in rural areas.

He acknowledged there’s no guarantee private schools will admit all applicants with scholarships but said there are “enough options out there” for those students.

“These scholarship dollars could also be used for transportation to whatever (school) you opt them into,” he said.

The Michigan Association of Public School Academies, the charter school advocacy association, supports the Let MI Kids Learn proposal.

Association president Dan Quisenberry said he sees the initiative as a way to increase funding to public schools. He envisions that parents of charter school students would ask their schools how to use the money and help create programming that a school may need. For example, that may be increasing internet access or implementing a new tutoring program.

He acknowledges that schools currently have money with federal COVID-19 relief money, but the tax credit opportunity scholarships would allow for ongoing help for schools.

Crunching the numbers

Opponents to Let MI Kids Learn have argued the program would deprive public schools of funds and lose the state hundreds of millions in tax credits.

Michigan uses a per-pupil funding model, meaning that public schools receive at least $8,700 for each student. If they were to leave, the public school would eventually lose that money.

If established, the program could cost the state $500 million in lost taxes in its first year and $1 billion by the fifth year, according to a Senate fiscal analysis on a similar legislative proposal last year. When Whitmer vetoed the legislation last year, she said the bill would turn private schools into “tax shelters for the wealthy.”

Multiple studies concluded such programs actually save states money — because states do not have to fund public schools as much when students leave for private schools.

A 2016 nationwide study conducted by EdChoice — a nationwide pro-school choice research organization — found tax-credit scholarship programs across the states saved $1.7 billion to $3.4 billion in taxpayer dollars during the 2013-14 school year.

The study relied on a simple formula. By assuming at least 60 percent of scholarship recipients are “switchers” — students who left public schools because of the program — researchers calculated the gap between the amount of money a state would have spent educating those kids and the funds the state loses in tax credits.

“When students leave public schools, officials have more room in their budgets to allocate resources for educating students that remain in those schools,” the study said.

Other studies have yielded similar results in states including Florida, where the state’s legislative research agency found that “taxpayers saved $1.49 in state education funding for every dollar loss in corporate income tax revenue.”

Critics such as the National Education Policy Center say the formula is based on “unfounded assumptions.”

In a 2016 review of the EdChoice study, researchers at Columbia University argue the report “overestimated” the amount of switchers, and multiple factors, including real estate development trends, could affect public and private school enrollment.

“Relying on changes in private school enrollment to extrapolate the rate of switchers is inaccurate and should not be substituted for actually tracking individual students who exit public schools and enroll in private schools,” the study contended.

Samuel E. Abrams, director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education at Teachers College at Columbia University, said efforts to privatize education do not address fixed costs.

He gave the analogy of a family where a child goes off to college. The parent still has a mortgage, utility bills and house upkeep 一 those are the fixed costs. The variable costs could be the food a parent would buy for their children.

“If you have a whole bunch of people, taking their kids out of the school district, and sending them to private schools, then you have that much less money to use for variable costs,” he said.

“So we do have research, and tuition tax credit scholarships, accordingly, do pose a substantial economic threat to school districts. There's no doubt about that.”

Quisenberry, of the charter school association, said he understands the program could incentivize people to leave public schools.

“We always believe — and our schools do — there's a reason parents come to us and choose us. That won't change. We want to be relevant, we want to meet the needs of those families and those students, even empowering the educators there. Yeah, they're going to have choices. This doesn't change that.”

“It's pretty hard to argue against additional choices when you are one,” he said.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!