Michigan has 1,100 voter drop boxes. GOP plan would lock them early.

June 23: GOP investigation finds no Michigan vote fraud, deems many claims ‘ludicrous’

May 5: Michigan GOP relaxes ballot drop box reform. Critics say plan is still unfair

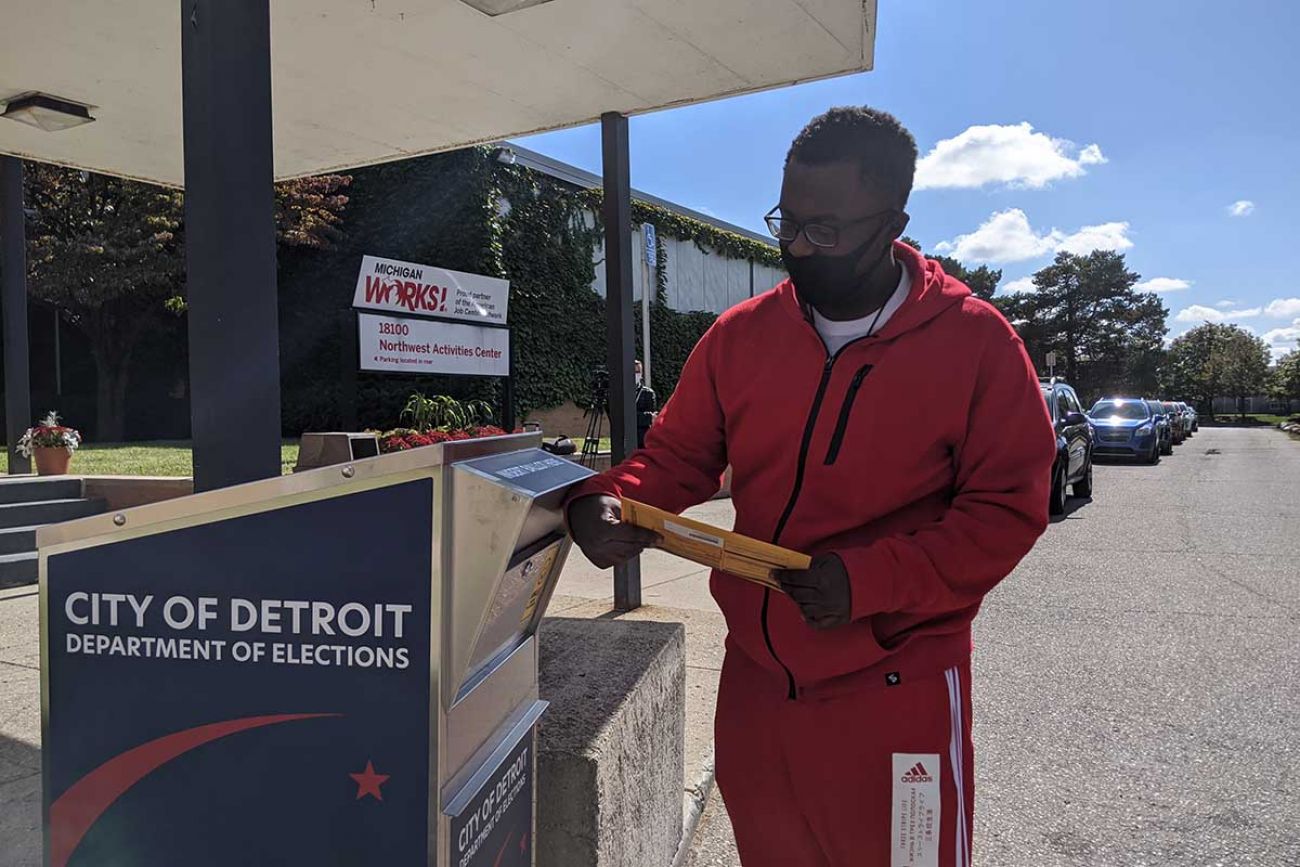

For 20-year-old Anton Willis, voting in his first presidential election was as easy as walking out his front door, crossing the street and putting his absentee ballot in a drop box outside the Northwest Activities Center in Detroit.

There was no line, no wait, no need to take time off work, no fear of lost mail and no risk of having to navigate a crowd in the midst of a global pandemic.

“It’s way more convenient than having to show up” at a polling place for in-person voting on Election Day, Willis told Bridge Michigan last fall as motorists lined up behind him to drop off their own ballots from the comfort of their cars.

Related:

- Michigan GOP proposes one day for early voting. Other states offer weeks.

- Q&A: Should CEO’s address social issues or stick to selling sneakers?

- Activists want to oust Michigan GOP director for saying Trump ‘blew it’ in 2020

- Michigan’s political geography is shifting. These interactive maps show how.

- We read all Michigan election reform bills. Many would add hurdles to voting.

As Senate Republicans push aggressive new regulations that would limit drop box usage — including a controversial requirement that they be locked a day before the polls close — state data provided to Bridge Michigan shows how ubiquitous they became last year amid a rapid expansion in absentee voting.

Bracing for a surge of absentee ballots, clerks around the state rushed to install drop boxes that gave voters a new option to ensure delivery of their ballot, especially those wary of mailing them given postal service delays.

Collectively, Michigan communities offered voters more than 1,125 drop boxes, a rapid expansion from prior elections, according to newly obtained data reported to the Secretary of State ahead of last year’s presidential election.

Election drop boxes in Michigan

There were over 1,100 drop boxes used during the 2020 general election, and they were utilized in communities across the state.

Source: Michigan Secretary of State

Detroit, Lansing and Flint each had at least a dozen drop boxes, but they were not exclusive to big cities or Democratic strongholds. More than 75 individual communities in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula used at least one drop box, as did many rural communities in other parts of the state.

But new drop box legislation proposed by Senate Republicans as part of sweeping election law bills threatens to limit the voter option in future contests, according to state and local election officials speaking out against the plan.

Among other things, the legislation — which Republicans may refashion into a statewide petition drive to avoid a veto from Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer — would prohibit voters from using absentee ballot drop boxes on Election Day and allow partisan boards to block their placement altogether.

Local clerks would be required to monitor all drop boxes with high-definition video cameras, plaster them with warnings against voter fraud and follow rigorous new reporting requirements to document ballot collection. As introduced, the Senate plan does not provide local governments with any funding to do so.

After a “successful election” in which absentee ballot drop boxes were used without any major security breaches, the legislation is a “solution in search of a problem,” said Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat.

The proposal “would really just end up leading to the dismantling and removal of drop boxes as a result of the prohibitive costs and requirements,” she warned.

Locking drop boxes

Senate Republicans say their proposed drop box regulations will ensure the process is secure and deter groups from collecting ballots and delivering them en masse, an activity known as “ballot harvesting” that is already illegal in Michigan.

There is no evidence of widespread ballot harvesting last year, but former President Donald Trump’s campaign raised the spectre in two Michigan lawsuits seeking to overturn the election won by Democratic President Joe Biden.

Michigan’s GOP-led Legislature spent months examining 2020 election allegations and did not find any evidence of “fraud that would have changed the outcome,” Majority Leader Mike Shirkey, R-Clarklake, said earlier this month.

“But we’ve found plenty of evidence of people questioning whether or not the process was of adequate integrity,” he said, acknowledging demand for reform has been generated by Trump loyalists that continue to believe false claims the election was rigged.

Legislation that would require clerks to lock drop boxes at 5 p.m. the day before an election is designed to “make sure (workers) have a chance to pick them up and get them to the clerk in time” to report results on election night, Shirkey said.

But prohibiting voters from using the boxes on Election Day would be “crazy” and “makes no sense at all,” said Winterfield Township Clerk Bonnie Blackledge, a Republican.

Like some other small-town clerks, Blackledge’s home is her office. She already has to check her mailbox for absentee ballots throughout Election Day and told Bridge Michigan it’s “just as easy to check the drop box at the same time.”

The legislation “would make it harder on the clerk, and it would make it harder on the voter,” Blackledge said. “If you care about the integrity of an election, you make sure you’re doing everything possible to make sure the voter can vote.”

There is no statewide tally on how many voters used drop boxes last year, but clerks say the option was popular given the pandemic and concerns over mail delays in the first presidential election since Michigan voters approved a constitutional amendment authorizing no-reason absentee voting.

“We processed about 41,000 absentee ballots, and 87 percent of them came in through drop boxes,” said Sterling Heights Clerk Melanie Ryska, who noted “the convenience of them being scattered throughout our community.”

About 3,000 of those absentee ballots were put in drop boxes on Election Day, and prohibiting that option in future elections would cause “massive voter confusion,” predicted Ryska, a nonpartisan appointee.

Sterling Heights promoted drop boxes on its website, Facebook and other social media sites, she said. “And then for a voter to pull up on a Monday evening before Election Day and find it to be closed? I find that incredibly confusing.”

Because it would be too late to mail in absentee ballots at that point, voters would have to drop them off inside their municipal clerk’s office. And that prospect worries local officials who said the 2018 amendment allowing same-day voter registration has already led to long lines in some offices on Election Day.

“We’re pretty much bombarded with same-day voter registration inside the clerk’s office, plus we’re fielding phone calls from precincts,” said Pontiac Clerk Garland Doyle. “So drop boxes were very convenient.”

An unfunded mandate

The GOP push for new drop box security regulations follows two isolated discoveries of unlocked boxes last year in Lansing that prompted the Michigan Republican Party to call for an investigation.

In one case, which occurred before absentee ballots were even mailed out, a company that installed a drop box forgot to lock it, said City Clerk Chris Swope.

In the second case, he said, staff didn’t properly close the handle on a box outside city hall, but it was monitored by video camera and “we have no evidence that any ballots were removed that should not have been.”

“Unfortunately, I think (lawmakers) are feeding into the lie that there was widespread fraud and catering to a base of people who believe that,” said Swope, a Democrat who leads the Michigan Association of Municipal Clerks.

Under a law adopted last fall, Michigan clerks who installed drop boxes after October 1 were required to monitor them with video cameras, but most boxes were installed before that provision took effect.

The new legislation would apply retroactively to drop boxes previously installed, requiring some clerks to buy new video equipment and requiring others to upgrade systems that do not meet the proposed specifications of 1080p resolution.

“I view it as an unfunded mandate,” said Ryska, of Sterling Heights.

Four of her city’s drop boxes are located at continually staffed fire stations that have security systems but don’t necessarily have cameras trained on the drop boxes at all times, she told Bridge Michigan.

In Chester Township, an Eaton County community with fewer than 2,000 residents, Republican Clerk Sheila Draper utilized two drop boxes last year: one at township hall, and one outside her home, which is also her official office.

Neither was monitored by video camera, she said, but both boxes are in visible areas with good lighting, and the township had “no issues last year.”

Forcing small towns with small budgets to purchase high-definition video cameras without providing the funding is a “stupid” idea, “and I think they better leave stuff alone,” Draper told Bridge Michigan.

“I’ve had no problems with my elections until the political party got into it.”

Big city, small town concerns

Any reduction in drop box access could have a disproportionate impact on voters in large cities with clerks who used them more aggressively last fall, according to a review of data provided by the Michigan Secretary of State.

Detroit, the state’s largest city by both population and land mass, used at least 32 drop boxes, according to state data. Lansing had 17 and Flint 12. Grand Rapids and Pontiac had seven each.

A majority of voters in each of those cities backed Biden over Trump, who had lambasted absentee ballot voting as a security risk but nonetheless encouraged his supporters to use the option.

“We received probably somewhere in the area of about 80 percent of our absentee ballots back through the drop boxes,” said Doyle, of Pontiac, who told Bridge he tried to make voting as convenient as possible by placing boxes centrally within each city council district.

“We had one outside city hall, but they were also in the neighborhoods at fire stations, community centers and schools, which are also polling locations,” he said. “We got more ballots back in the drop boxes than we actually did through the mail.”

Pontiac did monitor its drop boxes with video cameras, which officials generally agree is a best practice. But the city was able to purchase those cameras using private grant funding the Senate GOP plan would also prohibit in future elections.

More than 450 Michigan communities received COVID-19 election grants last year from the Center for Tech and Civil Life, a nonprofit funded by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Contrary to conspiracy theories, those grants were awarded to both Democratic and Republican clerks across the state.

“We got a lot of use” out of drop boxes and video cameras purchased with grant funding, said Flint City Clerk Inez Brown.

“I had secured people, two at a time, who went out daily to pick them up,” she said. “So the person’s vote is protected no matter what.”

Small-town Michigan clerks were less likely to use multiple absentee ballot drop boxes, but some who did told Bridge they fear the proposed regulations could be especially burdensome on them given their small staff size and limited budgets.

In Winterfield Township, a Clare County community with a population of fewer than 500 residents, Blackledge last year installed drop boxes outside of Township Hall and her home, which also doubles as her office because “we’re so small.”

She used private grant funding to buy surveillance equipment for both drop boxes, but the camera installed at her home was “a very low-cost model” that she doubts would meet the high-definition requirement of the Senate GOP legislation, meaning she’d likely need to buy another if the law is changed.

“I probably should keep my mouth shut, but I just sometimes feel like (lawmakers) go overboard just to make it harder for us,” said Blackledge, a Republican. “Our job is hard enough.”

Amendments still possible

The new legislation would require both the Secretary of State and county Board of Canvassers to approve all drop boxes in Michigan, a new layer of oversight that clerks fear could allow partisans to block their use altogether in some areas.

Under current law, each county board includes two Democrats and two Republicans. And if those two Republicans won’t vote to approve drop boxes, for instance, election officials in those counties couldn’t use them at all.

"I don't know that I trust people that tried to throw out my vote to certify my drop box," said Canton Township Clerk Siegrist, a Democrat who noted he and other voters were nearly disenfranchised last fall when Republicans on the Wayne County Board of Canvassers initially refused to certify the local results.

Sen. Ed McBroom, a Vulcan Republican who sponsored the drop box legislation, said it’s not his goal to allow partisan boards to bar their use. The legislation is intended to require review of the physical boxes — not their location — to ensure they meet security standards, and lawmakers may “clean up” the bill to make that clear, he told Bridge Michigan.

McBroom said he is also willing to consider amendments to his bill that would lock drop boxes the evening before the election. He echoed Shirkey’s claim the bill aims to eliminate potential Election Night bottlenecks that may arise as election workers empty drop boxes for the last time when polls close at 8 p.m.

“That means several workers spending hours collecting tens of thousands of ballots in the dark, late into the night,” McBroom said. “I was just trying to move all of that ahead and create some better efficiencies.”

Clerks say emptying ballot drop boxes wasn’t what caused delays in election results last year; It was the sheer volume of absentee ballots, which they were not legally allowed to begin counting until Election Day.

Local officials want permission to begin counting absentee ballots early, like in Florida, where clerks can begin counting — but not publicly reporting — absentee ballots 22 days before the election.

Senate Republicans refused to allow early counting last year, but Shirkey has since praised the system in Florida, a larger state that reported its full results more quickly than Michigan last year.

There is no early count period in the new Senate GOP plan, but “I wouldn’t count out the idea of still moving in that direction,” McBroom told Bridge Michigan, teasing a possible compromise.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!