Jesus Hitler, an ‘adrenaline junkie’ and the plot to train Michigan neo-Nazis

May 17: Michigan neo-Nazi leaders of The Base plead guilty to gang, gun charges

BAD AXE — Dressed in skull masks, fatigues and tactical vests, four men squeezed the triggers of their assault-style weapons and opened fire as a fifth man hoisted a Nazi flag behind them.

Filmed on a remote property in rural Michigan, the exercise that ended in a Hitler salute was featured in a 2020 video designed to help recruit members to The Base, a racist, militant and secretive neo-Nazi organization whose members trained for what they believed to be a coming race war.

The propaganda video was posted to social media by Justen Watkins, then 25. The former metro Detroiter had joined The Base a year earlier and quickly assumed a prominent role in the Michigan cell of the national organization.

Related:

- FBI: Neo-Nazi leader sought ‘white ethno-state’ in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

- Amid diversity debate, white supremacists recruit at Upper Peninsula school

- Michigan Tech condemned racism. Then it got ugly at Upper Peninsula university

Watkins was driven by “facism and adherence to the natural order — the way things are supposed to be,” he told leaders in a 2019 interview as he sought membership in The Base, according to a recording obtained by an Australian anti-fascist research organization called The White Rose Society and reviewed by Bridge Michigan.

The self-described “adrenaline junkie” bodybuilder had big ambitions: He wanted to use an elderly relative’s money to create a white nationalist compound in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula with no Jewish, Black or gay people.

“Buy me some god-damned land so I can train some fucking Nazis,” Watkins said in another recording obtained by researchers, referring to his step grandfather in a call with fellow Base members.

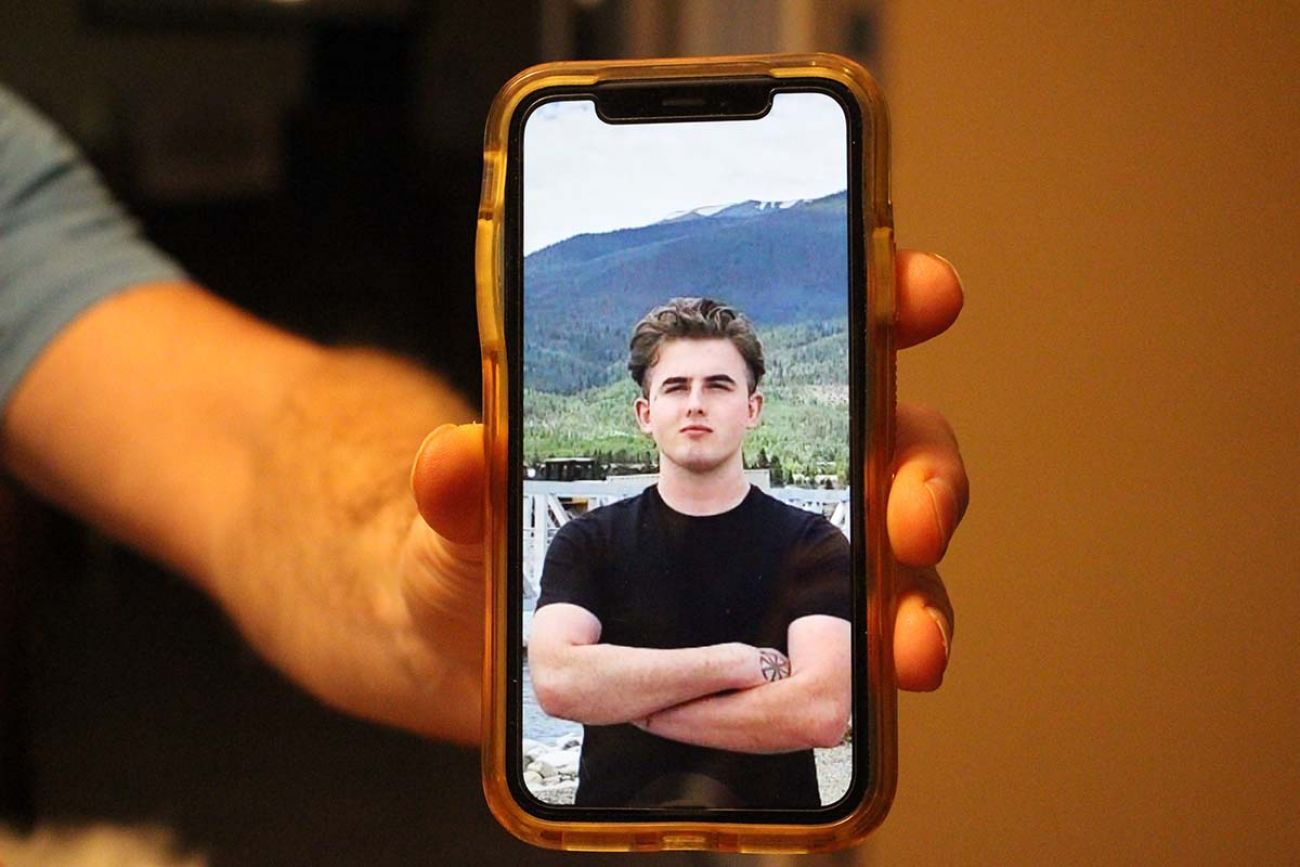

Watkins was planning the U.P. compound with Tristan Webb, a teen who had bonded with other white nationalists online after leaving a northern Michigan high school where was mocked as “Jesus Hitler.”

“The more land people buy, the better,” Webb said on the same recorded call. “We can take over counties and shit.”

The unlikely pair are now accused of various crimes, including gang membership, a 20-year felony charge that experts say reflects an aggressive approach by the government to try to stem the tide of growing extremist movements in Michigan and across the United States.

Aided by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, Bridge Michigan spent weeks reviewing court records and secret recordings showing how these young men allegedly became immersed in a testosterone-driven brotherhood fueled by anger, racism and the belief that society is doomed to collapse.

They were expecting race wars and preparing to win.

Family members who spoke with Bridge for this story said they did so in hopes that their experience could help other parents keep their children from succumbing to extremism.

“I never saw it going to this point, (but that was) being naive,” said Eric Webb, Tristan Webb’s father.

“That's where I'd tell any parent: Don't sit back and let it happen. You don't want to go in guns blazing and say, ‘You're not going to do this.’ But (you) definitely should be involved… The more open lines of communication the better.”

‘A brotherhood’

Webb was just 17 when he applied to join The Base, but he offered leaders a compelling asset: land.

He had recently moved with his mother to a family property in Bad Axe, where he promised to host paramilitary training exercises, according to internal recordings reviewed by Bridge.

Watkins, who considered himself a mentor to the teen and soon moved into his Bad Axe farmhouse, had already been accepted into the group after promising leaders he was “willing to actually do shit” and would not just “bounce when there’s trouble.”

Watkins’ brazen militantism and Webb’s land made them important to the neo-Nazi group. Less than a year after joining the group, and following a series of arrests in other states, Watkins declared in mid-2020 that he had been named the new national leader of The Base.

The reign was short-lived.

Watkins was arrested in October 2020, accused of harassing a Dexter family he mistakenly believed to be anti-fascist podcasters the prior year. Webb was charged in August 2021 after prosecutors accused him, Watkins and 32-year-old Thomas Denton of Wisconsin of trespassing on state property to scout for additional “hate camp” training locations.

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel charged all three men, along with Alfred Gorman, 36, of Taylor, with gang membership. All are headed toward trial, but court records indicate some are considering plea deals to reduce possible prison sentences in exchange for cooperative testimony.

"If we learned anything from the Oklahoma City bombing, it was that what happens in Michigan, doesn't necessarily stay in Michigan,” Nessel told Bridge Michigan. “And I think that's incumbent upon me as the attorney general of this state to be aggressive."

The Base is a small but bold faction in the neo-Nazi movement whose members portray themselves as vigilante soldiers defending the "European race" against a system that has been "infected" by Jewish values, according to the Anti-Defamation League.

It is among a number of "splinter groups" that emerged following the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and has been "very active" in Michigan, said Carolyn Normandin, regional director of ADL Michigan.

“It's not just kids sowing their wild oats,” she said. “These are usually grown adults. They've become part of a brotherhood, and their goal is to... accelerate violence to make (Jewish, Black and other minority) people go away.”

Among other things, the FBI says The Base is responsible for vandalizing an Upper Peninsula synagogue in Hancock in 2018, before Watkins and Webb had joined the group. Richard Tobin of New Jersey, who also organized a similar synagogue attack in Wisconsin, pleaded guilty and was recently sentenced to one year and one day in prison.

The Base has been thinned by a string of arrests, but it is "still significant" and "still operating," Normandin said. Meanwhile, similar groups like The Patriot Front and Folksfront have become active in Michigan, as evidenced by recent propaganda campaigns.

In Bad Axe, an overwhelmingly white city of about 3,000 people in the Thumb, residents said they barely noticed The Base militants, who were mostly from southeast Michigan and did not attract much attention in a region where many residents hunt and are accustomed to gunfire.

That changed in June 2020, when three armed men — who local authorities now believe to be Watkins, Webb and Denton — left the farmhouse compound to demonstrate at a Black Lives Matter rally in downtown Bad Axe, shocking protesters with their long guns, skull masks and Nazi salutes.

"It was a difficult day up here in Huron County," recalled Sheriff Kelly Hanson, who faced criticism for standing between the armed men and racial justice activists. He told Bridge Michigan he had tried to ease tension and prevent "something way worse.”

While Watkins, Webb and Denton did not identify themselves at the time, local authorities had "some idea" who the masked men were because state and federal authorities had been monitoring their farmhouse for months, Hanson said.

The Black Lives Matter clash “was a really big deal” for the typically quiet city, but Bad Axe residents had no idea at the time that the armed men were emerging leaders in a neo-Nazi group, said Sherie Shantz, a local coffee shop barista.

“Honestly, it’s not really surprising — for me at least, just because of the world right now,” Shantz said. “There’s idiots everywhere.”

‘Jesus Hitler’

Maybe it was the internet, where he had retreated after feeling “bullied” in one school and ostracized in another. Or his choice of music, which had grown increasingly heavy and dark.

Or perhaps it was the genetic kidney disorder that robbed him of his childhood dream of serving in the military.

Carole Teegardin can’t say for sure why her grandson, Tristan Webb, was drawn into white nationalism and eventually a neo-Nazi organization that she and his dad likened to a cult.

“I haven't been able to sleep for three years,” said Teegardin, a former Detroit Free Press journalist and playwright who told Bridge Michigan she had repeatedly alerted law enforcement officials to her grandson’s growing extremism. “I really love Tristan. I really wanted him to be OK.”

Webb, who is now 19, spent his early childhood in Macomb County, splitting time between New Baltimore and Chesterfield Township after his parents divorced when he was 5. They initially had joint custody and lived a mile apart. But as a teen, Webb moved north with his mom to Lake City in northern Michigan, and then to Bad Axe, while his dad stayed in metro Detroit.

Aside from the divorce and a couple behavioral issues that led his parents to try counseling on at least three occasions, Tristan Webb had a “healthy, normal” childhood, said Eric Webb, his father.

His son attended good schools and had “no major issues,” Webb said, but was “what you’d call an old soul” and had difficulty connecting with other kids his age.

“(Tristan) had Black friends and white, but he never got involved in any super-good close friendships,” Eric Webb recalled. “I think he just wanted to talk about adult things when kids wanted to be doing kid things.”

Before becoming a neo Nazi, Tristan Webb dabbled in Marxism and was fascinated with the revolutionary Che Guevera, his father said. Another time, he became obsessed with Nirvana, plastering his walls with band posters, dressing like singer Kurt Cobain and “would kind of hint around about suicide,” his father said.

His dad, who owned the Bad Axe farmhouse but did not live there or have custody of his son, isn’t sure when Webb began his online obsession with white nationalism.

But it was evident by mid-2018, when he was caught spreading propaganda at high school in Lake City.

“He had gone through so many phases, we just thought this whole Nazi thing would just be a phase, and he'd be out of that and realize that was stupid,” Eric Webb said, recalling how his teenage son had started spending hours on the phone and internet each day.

“This is where he got radicalized,” his dad surmised.

But in a December 2019 vetting interview with Base leaders, Tristan Webb claimed he was the one trying to radicalize others.

Webb claimed he organized meetups in the high school band room and delivered speeches at school. Classmates called him “Jesus Hitler” after he delivered a soliloquy while backlit from sunshine through a nearby window, he said in an interview recording shared by the White Rose Society.

Webb’s high school propaganda campaign made the local news. Lake City’s superintendent denounced “disruptions that involve hatred at their basis” but the Missaukee County sheriff determined Webb had not committed any crime.

By late 2019, as Webb sought membership in The Base, he told leaders he was already running his own organization called “Aryan Resistance” and described his religion as “esoteric Hitlerism,” a mystical interpretation of Nazism.

There is no “political solution” to fix what ails the United States, Webb said at the time.

“Every empire falls. Prepare for the fall. Train. And be with your own until then. Strength is through numbers. So if we’re all sitting in the city and not together, it’s going to be harder to mobilize when shit goes down.”

In Bad Axe, Webb said he hoped to create a separatist compound where he and like-minded individuals could live off the land and prepare for end times. He told leaders it could be a “safe house” for any Base member and promised to host “lots” of in-person meetings there.

Base leaders ultimately agreed to let Webb join, a decision they discussed after he had left the call, according to the recording.

“He's already offered his land, and he's doing it again,” said a man who identified himself as "Roman," an online persona reportedly used by the founder of The Base, Rinaldo Nazzaro, an America-born white supremacist based in Russia.

‘Hate is not a crime’

Justen Wakins sat in his car outside a Bad Axe gas station and pointed his cell phone camera at the modified assault-style gun he had stashed on the floor in front of the passenger seat.

As he panned up to show an armored truck, ostensibly parked to pick up cash from the gas station, his camera caught a brief glimpse of the middle school located across the street.

"Bout to play some GTA,” Watkins wrote atop the February 2020 video story he posted on Instagram, referencing the Grand Theft Auto video game series that gives players wide berth to commit crime and violence.

Watkins, who had recently moved with Tristan Webb at the Bad Axe farmhouse, was an aggressive social media user.

He routinely posted white supremacist memes and Base recruitment videos. He squabbled with other neo Nazis on extremist podcasts and YouTube channels.

In one video, posted on the Telegram social media site, Watkins gave a tour of his Bad Axe bedroom. Nazi flags adorned most walls and a computer table was cluttered with guns and ammunition.

A sticker clung to the window: “hate is not a crime.”

Watkins joined The Base in September of 2019 after a vetting interview that was recorded and obtained by the White Rose Society. During the interview, he told leaders he had been “red pilled” — or converted — to white nationalism as a teenager in metro Detroit, where he saw Chaldean and Albanian classmates stick up for each other in school.

“Any time one white kid would get in a fight with them, like 12 or 15 — who knows how many — of their cousins would show up and completely beat the kid’s ass,” Watkins said. “It never happened the other way. A white kid gets in a fight and nobody's backing them up. Naturally, things like that kind of puts things into perspective quick.”

That experience informed his world view, he told Base leaders: “No race mixing” or “degenerate stuff” like homosexuality. Jewish people, he continued, “are a separate racial identity. They're aliens to us in every way shape and form, taking over our culture.”

Watkins spent at least part of his youth in southeast Michigan, but it is not clear what high school he attended and was describing in his vetting interview. Family members who reside in St. Clair Shores did not respond to multiple interview requests from Bridge Michigan. And his attorney declined to discuss the case.

Assistant Attorney General Sunita Doddamani, head of Nessel’s state hate crimes and domestic terrorism unit, alleged Watkins had "expressed a desire... to die for the cause... and to take as many people with as he can with him."

He had “written a manifesto that calls for the killing and genocide of people," the prosecutor said in an October 2020 hearing shortly after Watkin’s initial arrest.

Watkins had previously entered Army Basic Training but did not graduate, according to the state. In a handwritten letter his sister posted to social media in 2013, a 17-year-old Watkins told family that his first three days of basic training were marked by sleep deprivation and a difficult guard duty assignment: Watching a "suicidal private" who was "being washed out."

In a recording of his 2019 vetting interview reviewed by Bridge, Watkins told Base leaders he had made early online connections to their movement through a Michigan “weapons board” he helped create on 4chan, an image-based bulletin board. He had recently joined Webb’s group, Aryan Resistance.

“I've kind of been kind of a mentor to him,” Watkins said of Webb, who was still 17 at the time. “He's kind of the Incel meme personified,” Watkins added, mocking his friend as a young man unable to attract women sexually. “I got him into weight lifting.”

Watkins repeatedly boasted about his own physique on social media, including posts made just weeks before the state police and FBI would arrest him. Among his current charges: alleged possession of steroids in Huron County.

“In a self-defense scenario against obesity, all fat fucks would be on a two week forced march with only water,” he wrote on Oct. 24, 2020, five days before his arrest. “Complete the march and come out lean, or drop out and die on the side of the road like they fucking deserve.”

Watkins, now 26-years-old and battling various charges in three counties, has been detained in the Washtenaw County Jail since May, when a judge revoked his bond because he had violated terms by communicating with another alleged member of the Base.

He had been living with Denton — the 32-year-old from Wisconsin — in a Bad Axe motel called Frank's Place. An FBI agent testified he found signs of continued gang activity in their room: A skull mask and a book called Siege, which is "required reading" for The Base.

The Base unravels

When applying for The Base, Watkins had described himself as a militant “adrenaline junkie” who had previously sparred online with Antifa activists but was not worried that he may one day be “doxxed” — or publicly exposed online.

“Doxxing is, in my opinion, a minor thing to worry about,” he said. “I've already doxxed myself and lost all my friends in the process, so I'm not too worried.”

But it was a dox-gone-wrong by Watkins that sparked a state and federal investigation that eventually led authorities to the Bad Axe property and the Michigan cell of The Base, which Watkins led.

Authorities allege that on Dec. 11, 2019, Watkins and Gorman, a 36-year-old Taylor accomplice, traveled to Dexter and took a "menacing" photo outside a home where they believed an anti-fascist podcast host lived. They proceeded to put up Base recruitment posters at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

A photo of a man believed to be Watkins — dressed in a skull mask and tactical gear on the porch of the Dexter home and pointing at its address — soon appeared on The Base’s Telegram channel as an apparent warning to the podcaster they had targeted.

An Anti-Defamation League staffer happened to be monitoring The Base's social media channels that day and captured the image, which "became very, very important to the FBI in solving that case," said Normandin, the ADL Michigan regional director.

The podcaster did not live at that home, however.

And the family that did — a couple with an infant child — called the police when they saw someone shining lights outside. Ten months later, authorities arrested Watkins and Gorman, who had allegedly found the address online after it was posted as part of a failed dox attempt by other white supremacists.

Three days after Watkins had allegedly taken the photo in Dexter, he and Webb told Base members they were preparing to host a weapons training exercise in Bad Axe in January 2020, according to a recording obtained by the White Rose Society and first reported by Vice.

Watkins bragged that he and Webb were also seeking land in the Upper Peninsula to expand their operations, a plan prosecutors allege was part of a long-held Base goal to establish a white ethno-state in rural Michigan or the Pacific Northwest.

In the audio call, Watkins claimed he had “red-pilled” his step-grandfather and was encouraging him to buy land in an unspecified part of the U.P., where the Neo-Nazi group hoped to “install” their own chief of police to ensure they would not face law enforcement pushback.

Their shared goal, Webb added, was to create a “community of compounds” in the U.P.

In God’s hands

By June 2020, Eric Webb had seen enough.

It was his gun that Tristan Webb had carried to the Black Lives Matter rally in Bad Axe, and he wanted it back, along with other weapons he had left at the family farmhouse that he owned and had used as a hunting retreat in prior years.

But the distressed dad’s trip north did not go well. While he was able to recover some weapons, Eric Webb ended the visit by calling police to report that his son, along with Watkins and Denton, had refused to return his “big assault gun.”

Webb, a Chesterfield Township optometrist, also claimed Watkins chased him to his car and attempted to punch him as he pulled away. Frustrated, he stopped talking to his son for “a while” after that, he told Bridge.

“I'm a Christian. I said, ‘I leave it to God’s hands,’ and I just left the situation,” Eric Webb recalled. “I had no idea it would become what it is.”

In internal discussions with fellow Base members, Tristan Webb said his mother, Jennifer Webb, got “pissed off” when they left beer bottles and trash in the Bad Axe home.

She declined to speak to Bridge, but her ex-husband blamed Watkins and Denton for corrupting their son.

“She knows she never should have let those two move in,” Webb said. “Those two being around (Tristan) just changed him. It was a change like parents who had their kids go on drugs would see.”

Eric Webb, who eventually sold the Bad Axe farm house where his ex-wife had lived, had considered evicting his son and friends last year but concluded he was unable because of a COVID-19 moratorium.

He had tried to intervene before. He had called Child Protective Services and attempted to gain custody after his son was caught spreading Nazi propaganda in Lake City, he said.

And he confronted his son again after another young white supremacist named “Lucien” had briefly lived in the Bad Axe home, recalled Teegardin, the grandmother.

“It’s the stuff you see on those television shows where the kid goes one way and the family goes the other,” Teegardin said. “I couldn’t believe it was Tristan. He began looking like a Proud Boy with a shaved head, the big boots, the wife beater shirts and fatigues every time we saw him.”

Tristan Webb, released on bond, is living with his mom again in a new town as he awaits trial. Since his August arrest, the teen has “voluntarily” talked with the FBI and attorney general’s office, his dad said, expressing hope his son may be able to reach a plea deal to avoid prison.

Court records indicate Gorman — the Taylor man accused of helping Watkins harass a family in Dexter — may be nearing a plea deal that would put him behind bars for at least two years but less than the maximum two decades.

Nessel’s office has offered to drop felony computer charges if Gorman pleads guilty to gang membership even though he had not yet been a fully vetted member of The Base. If Gorman accepts, prosecutors are asking a judge to sentence him to between 24 and 40 months.

Tristan Webb’s family has “come to grips with everything,” Eric Webb told Bridge Michigan. “No one’s mad at him, because we realize he’s paying the price for what he did.”

But his arrest was a “shock” because Tristan had already “left that behind” by moving out of the Bad Axe house and resuming communication with him, said Eric Webb, teling Bridge he now speaks to his son regularly and believes he is done with Neo-Nazism.

"He's lost the hatred," he said. “He's not at risk of going back into it, but I am afraid that if he gets sentenced to prison that could make him worse. I could lose my son.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!