Michigan shifts approach to monitor spread of deadly deer disease

State wildlife managers are launching a new strategy to track the deadly neurological disease that’s spreading through Michigan’s deer herds, abandoning a previous game plan that simultaneously overwhelmed state labs and produced underwhelming data.

Starting this fall, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources will scrap annual statewide testing for chronic wasting disease, which involves having deer hunters across Michigan submit heads of killed deer for testing. Under the new policy, DNR will focus on deer in rotating regions of the state each year and also enlist taxidermists and meat processors to submit samples.

The move signals a significant change for some Michigan hunters who may have grown accustomed to submitting deer heads into drop boxes or check stations to get them tested by DNR staff, free of charge. DNR officials say the more geographically targeted approach will cost the state less money while yielding better data about where chronic wasting disease is spreading.

The disease, which can infect deer, elk and moose, was first discovered in Michigan’s wild deer herd in 2015. Since then, it has cropped up in several counties in both peninsulas, prompting state officials to ban deer baiting throughout the lower peninsula, forbid hunters from moving deer carcasses out of counties with known infections, and liberalize hunting regulations in hopes of containing its spread.

Here’s what you need to know about the new approach:

What is chronic wasting disease?

It is a neurodegenerative illness that can live in an animal for a year or more before symptoms appear. Animals sick with CWD tend to stumble, starve, and eventually die. There is no vaccine or known treatment.

CWD doesn’t require animals to be in close proximity to spread. Proteins contained in animals’ feces, urine or saliva can spread through the soil or water. That’s why deer baiting can be a problem: Deer may contract CWD while gathering around a feed pile with other deer, or from eating from a pile previously visited by a sick deer.

Related:

- New push to make Michigan’s outdoors more inviting to people of color

- Lake Superior summer: Blue-green algae comes to a lake once believed immune

- Michigan hunters say wolves lowering deer numbers in U.P. Experts say no.

- Cougar sightings rise in Upper Peninsula after years of skepticism

- How bad is COVID? Even the deer test positive in Michigan. (Don’t be alarmed)

It’s not clear whether the disease can spread to people, and there have been no confirmed human cases. Still, the World Health Organization recommends avoiding infected meat and getting your meat tested if you harvest deer from an area where the disease is present.

So far, scientists have detected CWD in free-ranging deer in a handful of southwest Lower Peninsula counties and the Upper Peninsula’s Dickinson County. Montcalm County has been hardest-hit. But it is likely to spread elsewhere, particularly if steps aren’t taken to detect it before symptoms show, which is why scientists are eager to examine the lymph nodes of freshly killed deer in search of CWD proteins. Without a robust early detection system, the disease could easily spread undetected for years before state regulators noticed.

How does the new testing program work?

Rather than continuing to allow hunters across the state to submit deer heads, DNR officials plan to divide the state into five testing regions, then collect 8,000 to 10,000 samples from a single region each year, beginning with the southern Lower Peninsula.

When they’ve tested deer in all five areas of the state, they’ll start over.

DNR also is lessening its reliance on hunters in another way, by paying taxidermists and meat processors to submit many samples. Scott Whitcomb, the DNR’s senior advisor for wildlife and public lands, said the state will pay between $10 and $20 per deer head.

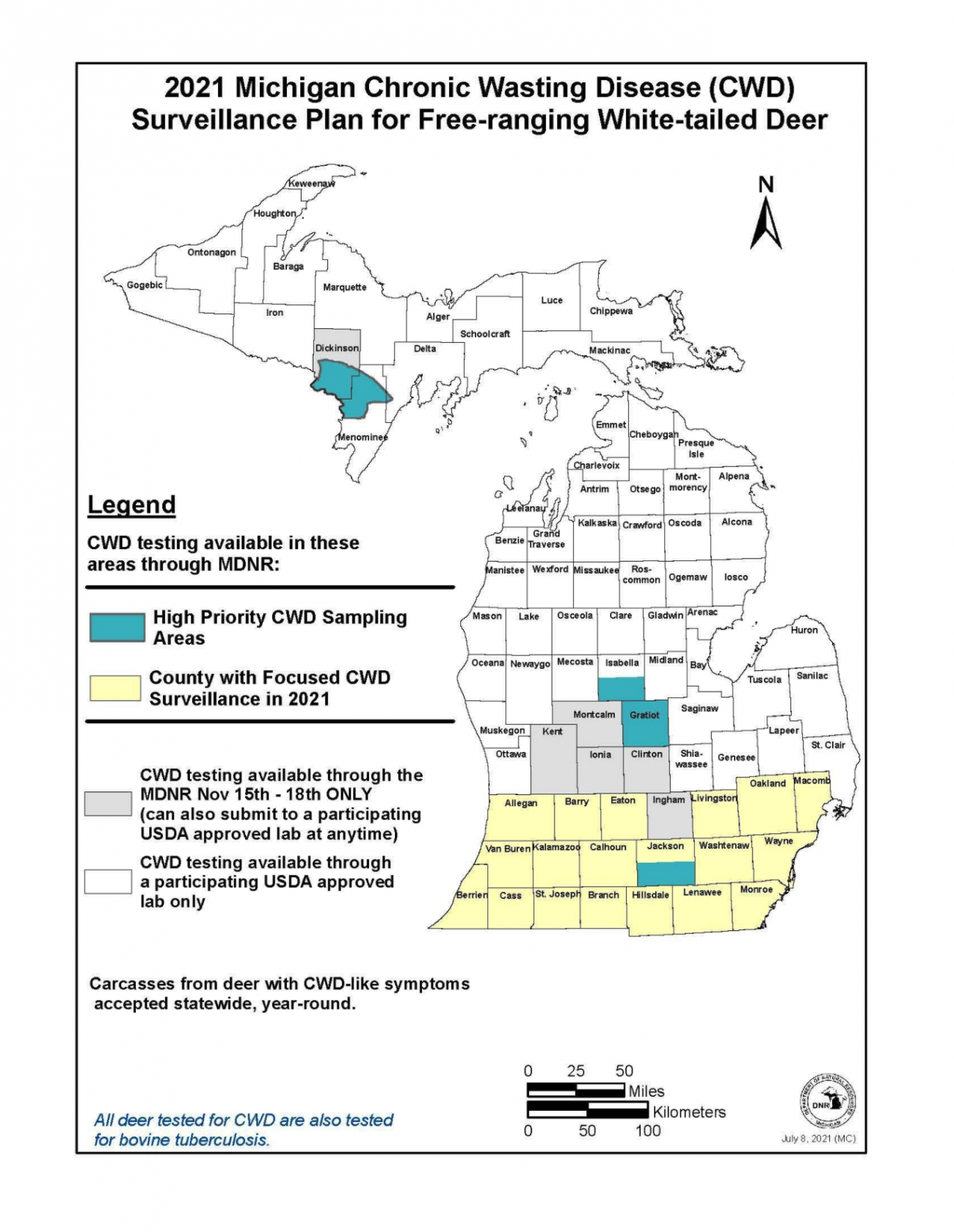

DNR will also accept hunter-submitted deer heads from a handful of counties listed here.

Ultimately, he said, the strategy will save time and money, because DNR staff won’t have to expend the time and resources to collect samples from across the state on their own.

Hunters outside the listed counties who have grown used to submitting their deer heads for testing might need to adjust.

If I bag a deer, can I still get it tested for CWD?

Yes, but perhaps not for free.

In addition to testing hunter submissions for free in targeted counties, DNR will continue to take samples of deer throughout the state that show chronic wasting disease symptoms.

Outside the counties the DNR is prioritizing this year, hunters who wish to get their deer meat tested will need to submit samples to a participating lab, at their own expense. The average cost, Whitcomb said, is about $25.

That may disappoint some hunters who wrongly viewed DNR’s testing program as a free service to help them decide whether their venison is safe to eat. But Whitcomb said DNR testing is intended solely to track disease; it was never meant to provide peace-of-mind for hunters, nor is the DNR’s testing method approved for determining food safety.

Why is the DNR changing its approach?

During a presentation last month before the Michigan Natural Resources Commission, DNR wildlife health section supervisor Kelly Straka summed it up this way: “If our goal is early detection, what we're doing is not going to be sustainable or effective long-term.”

Relying on hunter-submitted deer heads left DNR with less ability to target its surveillance.

State officials were testing massive numbers of deer — 30,756 in 2018 — yet still getting too little data from some counties while collecting huge amounts of data from places where they already knew CWD was present.

“Pretty soon, you’re just covering the same ground again and again,” Whitcomb said.

Meanwhile, the sheer volume of samples submitted was overwhelming the state disease testing lab. That showed up in tuberculosis outbreaks among lab staff, hefty overtime costs, and overtaxed lab equipment that at times neared its breaking point.

Under the new region-by-region strategy that focuses on detecting new outbreaks rather than revisiting old ones, Whitcomb said, the DNR will be better able to keep tabs on CWD while keeping workers safe and conserving state resources.

By the end of a five-year cycle, he said, “we’ll probably have a good idea of the geographic extent of the disease.”

Will the new approach help snuff out CWD in Michigan?

Probably not, at least in the near-term.

There is no treatment or vaccine for CWD, so for now, the best state wildlife managers can do is attempt to contain the disease.

“The strategy becomes to keep (the spread) as slow as you can for as long as you can...hoping that a cure or some other mitigation arises” Whitcomb said.

If a treatment becomes available, Whitcomb said, wildlife managers will have an easier time administering it if they know where the sick deer are located.

I don’t hunt. Why should I care?

From an animal welfare standpoint, Whitcomb said, “what it does to an animal is just sickening.” Infected deer suffer — starving, drooling and stumbling until they eventually die.

And if CWD became widespread, it could drive down deer populations. Michigan’s deer herds are robust, but a major drop in numbers could create a gap in the food web, affecting other animals.

And while CWD hasn’t yet infected humans, there’s still a chance it could. As Michigan learned after a sample of Michigan deer tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies, diseases can move fairly easily between deer and humans.

Containing CWD infections within Michigan’s deer herds also keeps the risk of human transmission low.

How will DNR respond if testing shows CWD is spreading to new areas?

That will be determined on a case by case basis, Whitcomb said.

One of the main tools for controlling CWD is increasing hunting pressure to thin deer herds in hopes of reducing opportunities for disease to spread, and Whitcomb said most of Michigan’s deer regulations are already relatively liberal, allowing hunters to kill many deer.

That’s not to say DNR wouldn’t ramp up regulations in newly-infected areas, he said. But “a big part of it is informing hunters,” who can then take their own precautions to prevent CWD spread, such as properly disposing of deer carcasses and disinfecting their equipment.

“Unfortunately, as a natural resources manager, you don’t have a lot of silver bullets with CWD,” he said.

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!