Michigan mallards are in decline. Are domestic ducks weakening their genes?

- Michigan’s mallard duck population has been waning for years

- Genetic mixing with domestic ducks may be to blame

After a brief rebound last year, Michigan’s mallard duck populations have continued a decades-long decline that has scientists eyeing game farms as a possible culprit.

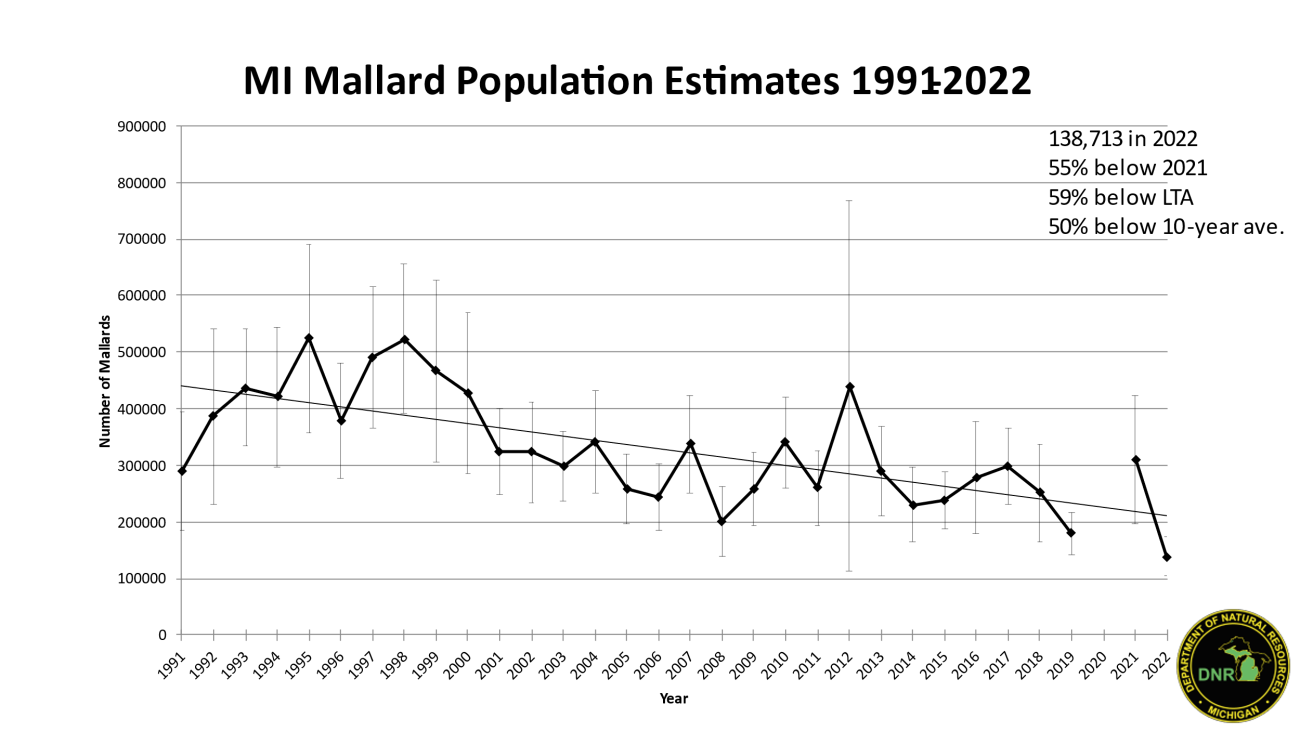

Mallard populations throughout the mid-continent have been on the rise since the early 2000s, but the subgroup that frequents the Great Lakes has shrunk from more than 500,000 birds in 1995 to fewer than 140,000 today.

“It’s not just Michigan, but in Wisconsin and in Minnesota as well,” said Barbara Avers, a waterfowl and wetland specialist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “We’ve been concerned about it for quite some time.”

Related:

- Duck and goose populations booming in Michigan. Other birds? Not so much.

- Intense storms from climate change harming Michigan streams and river

- Broad support cited for expanding Michigan wetlands

Avers presented the latest figures to members of Michigan’s Natural Resources Commission Thursday. Surveyors counted 138,713 mallards last year, down 55 percent from 2021 and 59 percent below long-term averages.

“That was despite having some pretty decent breeding habitat conditions” for the wetland-loving birds, Avers told the commission.

Higher-than-usual survey numbers in 2021 had prompted hope for a mallard rebound, but Avers said surveying issues may have resulted in an overcount.

For now, staff at the Michigan Department of Natural Resources are recommending no changes to how Michigan manages ducks, in part because hunting doesn’t seem to be causing the declines. A mix of other factors may be to blame, Avers said, from climate change to habitat loss caused by suburban sprawl.

But scientists are increasingly concerned about a third possibility: Genetic weakening caused by humans releasing domesticated ducks into the wild.

Commercial game farms in eastern states and the Great Lakes have long raised and released mallard-like domestic ducks for hunters to target. Nearly identical to wild mallards in appearance, these captive-raised ducks have different genes and are considered a different species, said Ben Luukkonen, a Michigan State University Ph.D. student who is studying the Great Lakes mallard declines.

At one point, as many as half-a-million of them were released each year in the Atlantic Flyway alone. Mallard declines in those states, Lukkonen said, “coincide with the areas where the most domestic game farm mallards have been released.”

So far, about half of birds sampled through Luukkonen’s Great Lakes region study are a genetic cross between wild mallards and their farm-raised relatives.

There is evidence to suggest that, like barnyard chickens, those domestic mallards are not built for life in the wild, Avers said. They’re bad at making nests, and worse at diligently sitting on them. They feed differently, don’t migrate as readily, and they tend to favor urban areas over natural wetlands.

Add it all up, and hybridization may have left Michigan’s flocks “not as fit for survival,” Avers said.

While state species managers await the results of Luukkonen’s study, Avers said they’re recommending no changes to duck hunting regulations, which allow up to six ducks-per-day during a 60-day season. Research has shown that hunting pressure isn't driving down mallard populations, Avers said.

Unfortunately, said Joe Genzel, a regional spokesperson for the waterfowl conservation group Ducks Unlimited, the damage done by a century of releasing domesticated ducks into the wild is irreversible.

“The genes are already there,” Genzel said. “You can’t go back to the ‘50s and ‘60s and tell those folks not to stock their game farms with mallards.”

But there is some hope of reversing wetland losses that have also imperiled ducks. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on Wednesday signed a supplemental budget that dedicates $10 million to wetland restoration in the Saginaw Bay and Lake Erie watersheds.

Advocacy groups including Ducks Unlimited had asked for $30 million. But Genzel said the lesser amount is still a win for waterfowl habitat and water quality in the Great Lakes.

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!