The Great Lakes go digital as smart buoy network launches in Lake Erie

Lake Erie is the first of the Great Lakes getting connected to the internet with a series of offshore “smart” buoys.

And it’s not just for sending texts on the water. The buoy project, called the Smart Lake Erie Watershed Initiative, is providing invaluable data to researchers and anglers.

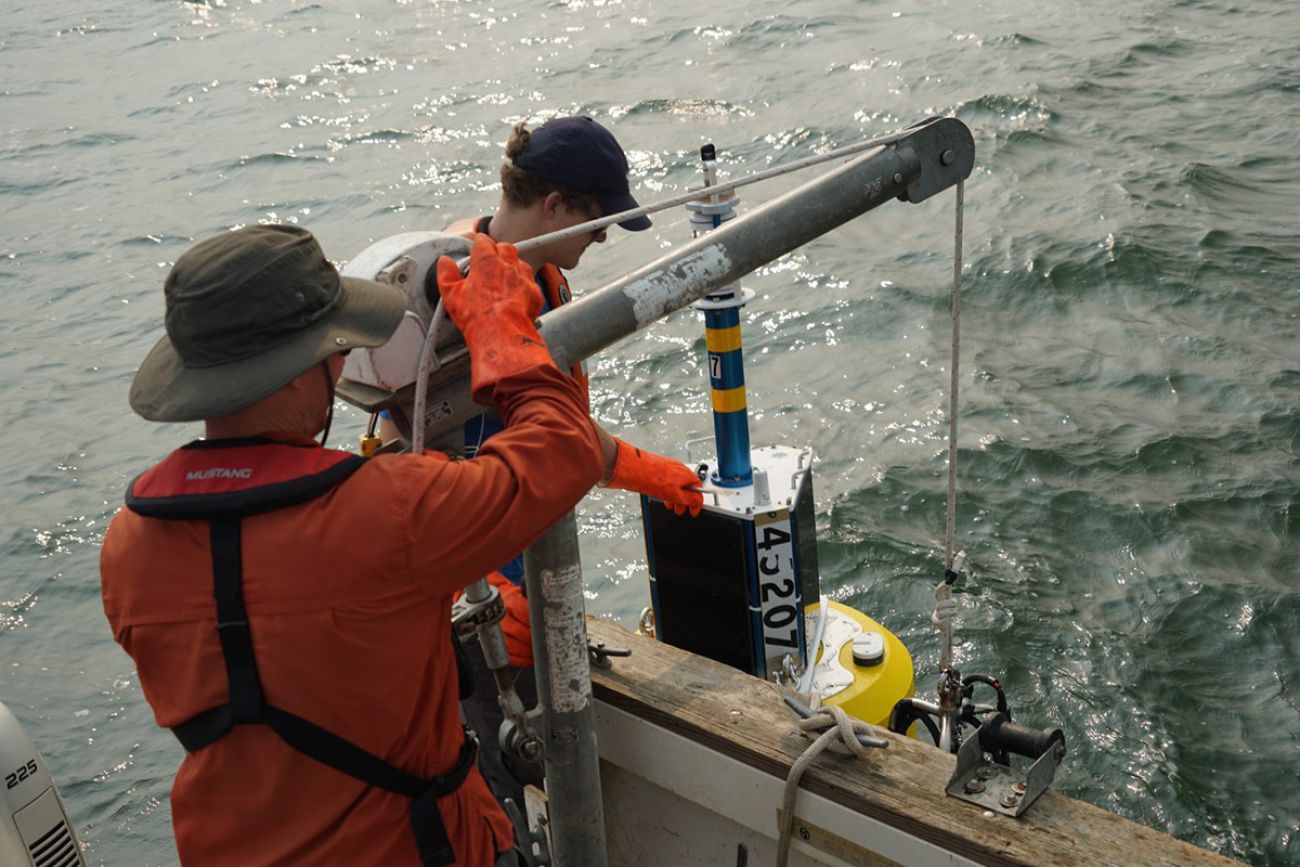

The initiative was created by the Cleveland Water Alliance, a group that protects and improves how the Great Lakes are used in Ohio. The alliance works with a local engineering group, Freeboard Technology, to develop and deploy the buoys.

Smart Lake Erie makes water conditions, contaminants and nutrients easily accessible, said Ed Verhamme, Freeboard Technology’s president. Eventually it will be available across all of the Great Lakes.

Related:

- Whitefish are on brink in Michigan. Can they learn to love rivers to survive?

- Warmer winters mean less ice on Lake Michigan, hurting trout and whitefish

- A big fight in Lansing over fishing rules on the Great Lakes

Smart Lake Erie is an infrastructure investment that will better prepare the region for harmful algal blooms, oil spills and the consequences of climate change, experts say.

“We really take for granted how easy it is on land to provide (cellular) coverage,” Verhamme said. “With the network, it’s going to be easier and cheaper to monitor the Great Lakes.”

Other methods of connecting to the internet on the water — cell modems and satellite telemetry — are expensive and inconvenient, Verhamme said. But Smart Lake Erie allows users to directly connect their devices through short-wave radio.

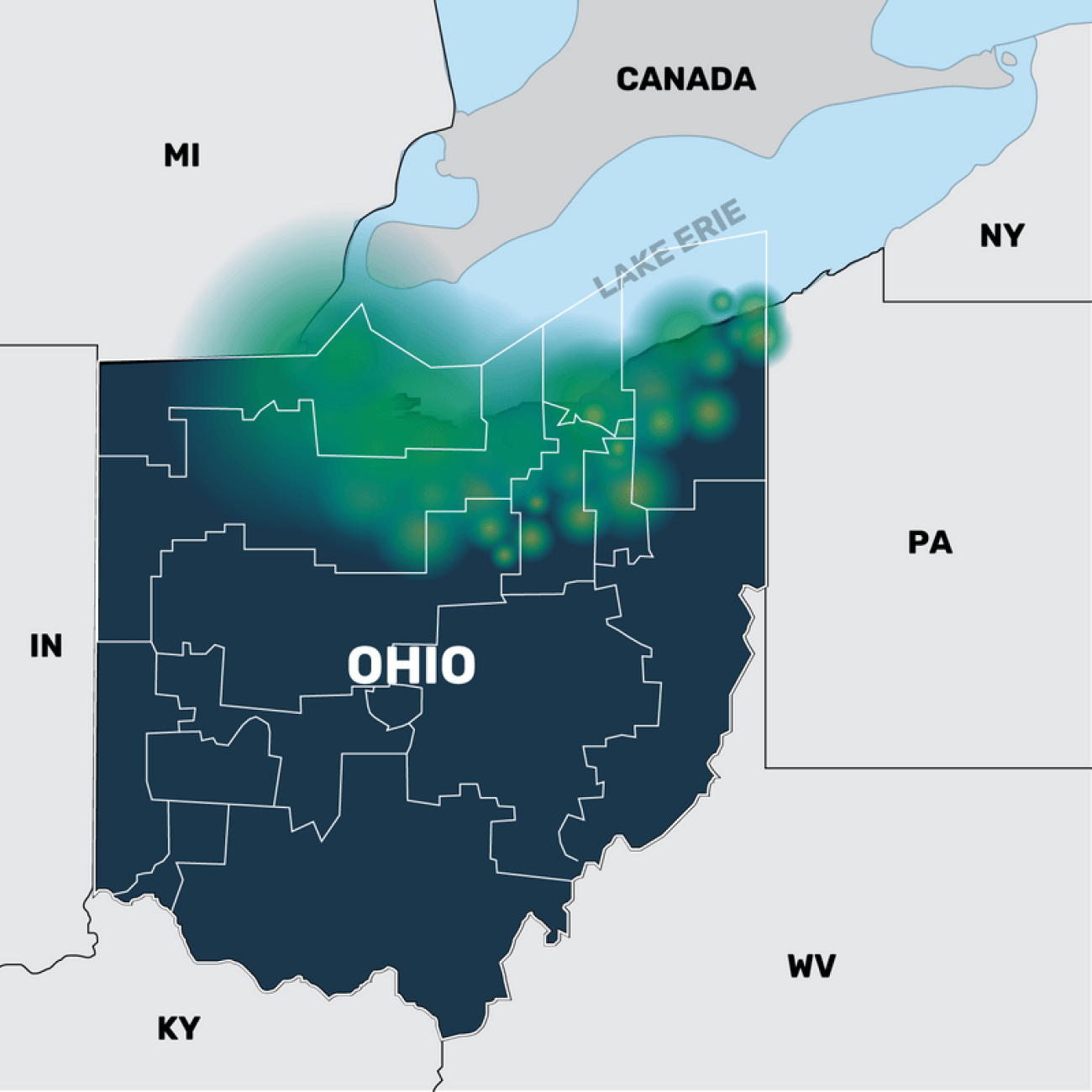

The goal is to have over 200 sensors in buoys and cell towers in the network to provide over 12,000 square miles of coverage, Verhamme said. Right now, about half of the area is covered, with service available over 20 miles off the Ohio coast. That includes parts of Lake Erie and nearby wetlands that drain into it.

The complete project, Smart Great Lakes, will provide coverage to populated areas of Lake Michigan, Lake Huron and Lake Superior with over 300 buoys, Verhamme said.

Each buoy can monitor local weather and water conditions such as temperature, depth and contaminant concentrations. The data is publicly available and can be accessed by texting the buoy.

Safety

Public safety is one of Smart Lake Erie’s many uses, Verhamme said. Sensors can detect changes in water depth, wind speed and changes in humidity to alert boaters of an approaching storm.

“Lake Erie is a phenomenal resource,” Verhamme said. “We know it’s got billions of dollars of economic value to the region and we think there’s some technology that can lower the risk for people to be out on the lake and also be safer while they do it.”

Climate monitoring

The buoy networks are also revolutionizing climate monitoring in the Great Lakes, said Steve Ruberg, a researcher for the Observing Systems and Advanced Technology branch of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Right now, most information collected on the water is retrieved from buoys about once a year. With the buoy network, the same information is available in an instant.

“You can’t really make good decisions unless you have good data,” Ruberg said.

One of Ruberg’s longest projects — a 30-year study of Great Lakes temperatures — shows that the region’s winter season is shorteniong. This change has disturbed the lake’s nutrient cycling, which is vital for organisms to survive.

Poor nutrient cycling can harmt fish populations, Ruberg said. Collecting real-time data on water conditions using Smart Great Lakes could allow decision-makers and fisheries to respond to the effects of climate change faster.

“There are folks making decisions about stocking additional fish and folks making decisions about trying to restore native fishes, such as whitefish,” he said. “It could inform decisions like that.”

Algal blooms

In addition to NOAA, researchers at Michigan Technological University and Lake Superior State University have been collaborating with Freeboard Technology on water studies leveraging the expansive network, Verhamme said.

One proposed study would deploy small “drifters” that float through the water to map the path of algal blooms. The buoy network would relay their location and the local algae concentration in real-time.

Similar drifters cost over $10,000 to equip with the power and radios needed to communicate with satellites, Verhamme said. But his team has gotten the price down to about $500.

“People will see it’s going to be easier and cheaper to monitor the Great Lakes, understand the movement of harmful algal blooms,” he said. “Most scientists would agree it’s going to help us understand these as well as know how to manage them in the future.”

Oil spills

Christopher Pace, chief of the Great Lakes Center for Oil Spill Expertise, said Smart Lake Erie helps the U.S. Coast Guard prepare for oil spills.

“Their Lake Erie network, it’s really, I would say groundbreaking with the amount of data available and the grid system that they’ve set up there,” Pace said.

The Great Lakes Commission reported in 2017 that the coasts of Toledo and Buffalo have the highest risk of an oil spill that would be “devastating” to protected fish and wildlife populations and their habitats.

“The Great Lakes present a unique challenge for oil spills,” Pace said. Spills are harder to detect in the winter because of ice cover, and not enough data is available to know if oil cleanup methods, like controlled burning, are safe for freshwater.

But with Smart Lake Erie, buoys near these areas could detect hydrocarbons in the water, allowing spills and their range of impact to be detected early.

With the help of Limno Tech, another engineering company Verhamme helps lead, Lake Superior State University is helping the U.S. Coast Guard test hydrocarbon sensors.

“While hydrocarbons aren’t their specific focus, it helps us start to understand what monitoring in the Great Lakes or early detection of oil spills might look like,” Pace said.

“While hydrocarbons aren’t their specific focus, it helps us start to understand what monitoring in the Great Lakes or early detection of oil spills might look like,” he said.

And the buoy network is key to making the sensors possible.

“A lot of these sensors exist in the federal arsenal, but at a cost many times more than what the teams here in the Great Lakes region are employing,” Pace said. “That’s because they’re taking some innovative approaches to off-the-shelf equipment and modifying it to meet the needs of the Great Lakes region.

“And that’s really empowering.”

The idea is to use technology to help scientists better understand biology and ecology, Verhamme said. “We’re showing them how we can use this tech and helping them unlock their creativity for problem solving.”

The Great Lakes Echo originally published this story

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!