Flint residents unimpressed by Snyder charges linked to lead poisoning

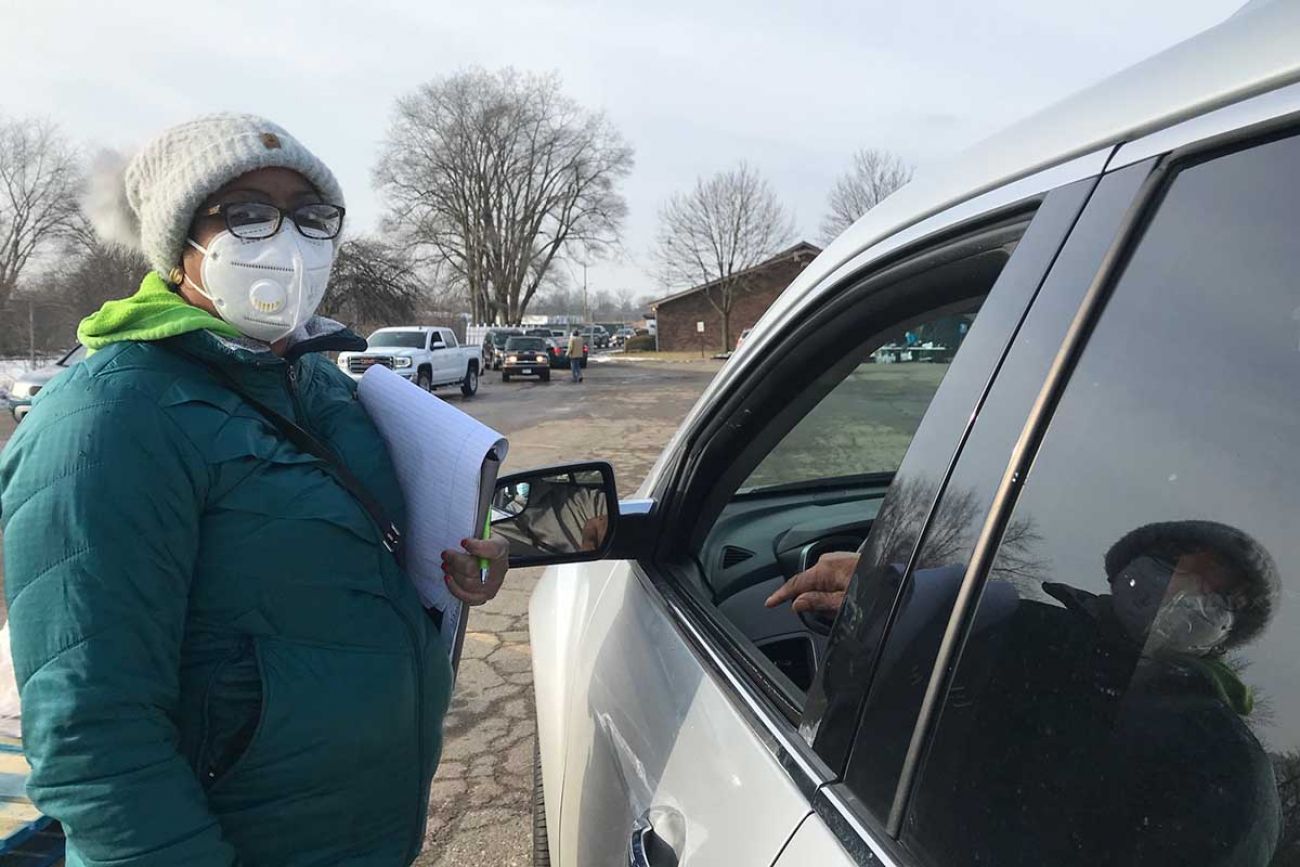

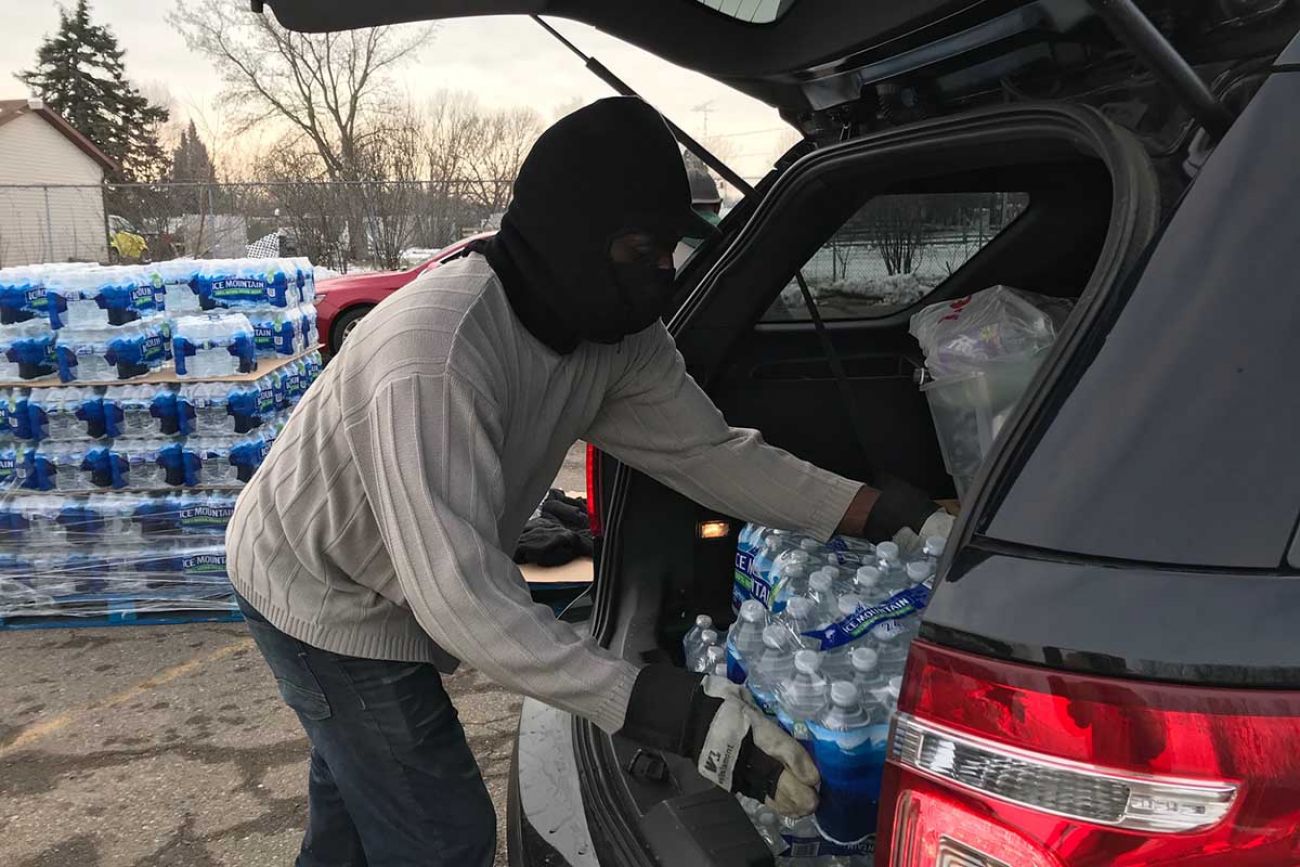

FLINT—As volunteers loaded her trunk with cases of bottled water Thursday at the RL Jones Community Outreach Center, a weekly ritual that involves waiting for hours in a line of cars that snakes far down the highway, Paula Stephenson simmered with anger.

Days after Flint residents learned that former Gov. Rick Snyder and other officials would face criminal charges for their role in the water crisis that poisoned Flint residents, news emerged that Snyder would face two misdemeanors for, in Stephenson’s words, “destroying us.”

“It’s a slap in the face,” said Stephenson, 59.

Snyder pleaded not guilty Thursday to two counts of willful neglect of duty, a misdemeanor punishable by up to one-year in prison and/or a $1,000 fine. Prosecutors on Thursday also announced felony charges against several of his former aides and appointees.

In the years since drinking Flint’s tainted water, Stephenson said she has suffered memory loss, chronic headaches, recurring nausea and psychological trauma that has left her unwilling to drink tap water, in Flint or anywhere else.

A $1,000 fine, she said, “is not even taking away gas for his boat for the weekend. Why doesn’t Snyder get his ass out here and volunteer? Why doesn’t he sit in line for hours to hike water home every week?”

Other former officials face more serious charges. Nick Lyon, the former director of Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, faces nine counts of involuntary manslaughter. So does former Chief Medical Executive Eden Wells. Former Snyder aide Rich Baird, former chief of staff Jarrod Agen, and former Flint emergency managers Darnell Earley and Gerald Ambrose all face felonies, too.

While Flint residents said they’re glad to see criminal charges after years of waiting, anger was the prevailing sentiment Thursday morning as they learned the specifics of the unfolding criminal charges, and compared Snyder’s possible fate to their own.

Ali Griffith, 52, considered the charges against Snyder to be another example of the racial and class divide that underpinned the water crisis in the majority Black city with a 39 percent poverty rate. Now, he said, it’s showing up in the form of charges that each could give Snyder a maximum of a $1,000 fine and a year in jail, while Griffith’s life is still impacted, he said, by long-past felony drug offenses.

“It’s murder and it should be charged that way,” said Griffith, noting the deaths of several residents following possible exposure. He said he and his teenage son have suffered lingering medical and behavioral problems they believe are connected to drinking Flint’s water.

Many characterized Snyder’s sentence if he’s convicted as an insult to a community that has watched, time and again, as powerful outsiders made decisions for their city and faced few consequences for their failures.

The 2014 switch from Detroit’s water system to the corrosive Flint River — a cost-cutting measure made by Snyder-appointed emergency managers after stripping governing authority from local voters and elected officials — caused lead to leach from the city’s pipes and into its drinking water. As residents complained of murky and putrid water coming from their tap, state officials downplayed their concerns for more than a year and assured them the water was safe.

Only in October 2015, a year-and-a-half into the crisis and following the independent findings of, among others, a local pediatrician and outside investigators, did Snyder administration officials acknowledge something was wrong and stop piping Flint River water into residents’ homes.

Flint residents, said Leon El-Alamin, founder and executive director of the city’s M.A.D.E. Institute, which serves at-risk youth and people returning from jail or prison, have been physically harmed and psychologically traumatized by the crisis in ways that can’t be fixed by sending someone to prison.

The seeds of that harm began far before Flint switched water sources, he said.

“When you look at the police brutality. When you look at the redlining. When you look at the gentrification in this community, that’s targeting mostly Black and poor white folks. We’re never going to trust the government.”

That mistrust is evident in the many Flint residents who still drink only bottled water, even after nearly all of the city’s lead service lines have been removed and government officials’ insist that the water is safe to drink.

It’s evident in community activists’ doubts about a $641 million legal settlement intended to financially compensate Flint residents for the suffering they’ve endured — and will continue to endure — as a result of drinking contaminated water.

It is not safe to ingest lead, a powerful neurotoxin that causes irreversible damage. Lead is particularly damaging to children’s developing brains, and can stunt their growth and cause permanent learning, hearing, speech and behavior problems.

Many of the consequences of lead exposure manifest years or even decades after children are exposed, in the form of increased criminal justice costs, special education costs, health care costs, mental health costs and decreased economic activity, pediatrician Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, whose research helped expose Flint’s lead crisis, recently told Bridge Michigan.

Hanna-Attisha, who is working on a paper about the economic gains Michigan stands to achieve as part of its 20-year plan to remove all of the state’s lead service lines, said U.S. economic losses tied to lead poisoning amount to tens of billions of dollars a year.

In a statement Tuesday responding to early news that Snyder and others would face criminal charges, Hanna-Attisha called it a step toward justice for a community “poisoned by policies.” But she said “healing wounds & restoring trust will take decades & long-term resources.”

Perhaps most important among those resources are programs to help children who’ve been exposed to lead succeed in school and life, said Annie Whitlock, chair of the education department at the University of Michigan-Flint.

Related stories:

- Snyder, top aides charged in Flint water crisis. Is that justice?

- Snyder allies: Flint charges may have ‘chilling effect’ on government

Whitlock was pregnant when she unknowingly drank lead-tainted water from the taps at work. Her daughter, now school-aged, has autism and has experienced developmental delays. Whitlock can’t help but wonder whether lead exposure in the uterus had something to do with it.

“Now imagine kids like her, thousands of them, all entering kindergarten in the same school district,” Whitlock said.

That’s what Flint must deal with. In the nearly seven years since the crisis began, Flint has already experienced a sharp uptick in special education needs among its students.

The percentage of Flint school district students who qualify for special education stood at nearly 23 percent in the 2019-20 school year, a dramatic rise since the crisis began, according to state figures. During the 2014-15 school year, the figure was 15 percent. Michigan’s statewide average last school year was 13.5 percent.

Some experts expect those numbers to keep rising as children exposed to lead continue to filter into the school system and receive diagnoses for learning disabilities.

Whitlock said those statistics have changed the way UM-Flint instructors train rising educators. Many of them will go on to teach in Flint-area schools, Whitlock said, and they must be prepared for classrooms where high numbers of students have special learning needs arising from lead exposure.

They also must be prepared to teach children who, for good reason, distrust government authority figures and “might come to school and think, why would this teacher be any different?”

With long-term investment in services that cater to the children of Flint, Whitlock said, “there’s no reason to count this generation of kids out.”

But it’s going to take long-term, heavy investment to provide appropriate education for Flint students exposed to lead, she said.

As part of a legal settlement with the state, the city of Flint, McLaren Regional Medical Center and Rowe Professional Services Co. (a Flint-based engineering firm involved in the 2014 water switch), special education programs in Flint area school districts will receive $9 million in additional funding. A spokeswoman for the school district declined to connect a Bridge Michigan reporter with a school official.

Lawyers representing city residents in the $641 million class-action settlement have urged eligible residents to sign on. It’s not perfect, co-lead attorney Michael Pitt said in August, but “overall, it is very good.”

Nearly 80 percent of funds distributed to Flint residents would go to children who were minors when first exposed to Flint River water, while adults will get about 18 percent.

But many community activists say the pot of money is too small, and the settlement’s terms leave too many residents ineligible for funds.

“It’s not fair, and it’s not enough,” said Bishop Bernadel Jefferson of Faith Deliverance Center Church.

El-Alamin said he and some other community activists are particularly concerned that the settlement provides too little relief to Flint adults who suffered as a result of the crisis.

“How do you think the kids get taken to the doctor, to get the lead testing, the bottled water that we’ve got to pay for and pick up?” he said. “We suffer just as much as our babies. We're the ones that have continued to try to raise these kids, but we can't keep doing that on a shoestring budget with no real resources.”

Other Flint residents interviewed Thursday said it’s insulting that after everything they’ve been through, they now must go through an onerous claims process to prove they qualify for compensation.

“Everyone living in the city at that time should get something,” said Tommy Tucker, 56.

Claimants are being told to submit documentation to prove they qualify for one of the settlement's 30 claims categories (listed on pages 379 to 422 of this document). In some cases, that might include bone lead tests, records showing they’ve experienced health problems, miscarriages, property damage or other issues.

U.S. District Judge Judge Judith Levy has said she plans to decide by Jan. 21 whether to preliminarily approve the settlement, enabling residents to start lining up to file claims. If she does, the settlement must still receive final approval following a public hearing and other procedural steps.

But “there’s no amount of money that will fix what it did to our bodies,” Kaleka Lewis, coordinator of the food and water distribution program at RL Jones, as she helped residents early Thursday.

“Here we are years later, people lining up at 11 or 12 o’clock at night to get food and water,” she said.

“People think it’s over. It’s not over.”

Bridge reporter Ron French contributed to this report.

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!