After decades of neglect, bill coming due for Michigan’s water infrastructure

PONTIAC – Six years ago a panel of experts convened by former Gov. Rick Snyder concluded that Michigan’s public works — its roads, sewers, water distribution pipes, and other vital systems — were in “a state of disrepair.” The panel’s report argued that Michigan, which set the standard for industrial development and economic opportunity in the 20th century, was losing competitive advantage in a globalized economy by not investing in fundamental connective assets like potable water and wastewater treatment. The report came at a low point in the state’s public works history: a year after the dimensions of catastrophic blunders in managing Flint’s drinking water system were laid bare.

Water’s True Cost

Throughout the Great Lakes region and across the U.S., water systems are aging. In some communities, this means water bills that residents can’t afford or water that’s unsafe to drink. From shrinking cities and small towns to the comparatively thriving suburbs, the true cost of water has been deferred for decades. As the nation prepares to pour hundreds of billions of federal dollars into rescuing water systems, the Great Lakes News Collaborative investigates the true cost of water in Michigan. Read the rest of the series here.

Since the report’s publication, though, Michigan appears to be positioning itself on the cusp of renewal. The quality of the state’s water infrastructure and the consequences of failure, while still real and apparent, are no longer being ignored.

In large part that is due to rare bipartisanship in Michigan and the country around water-related policy. The roughly $50 billion for water and sewer systems in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, signed into law by President Joe Biden last November, will be the largest federal infusion of money into the sector in a half century, ever since the construction grants program built modern sewage treatment following enactment of the Clean Water Act.

Related:

- Many rural towns have neglected drinking water systems for decades

- Water woes loom for Michigan suburbs, towns after decades of disinvestment

- High costs, few customers: Benton Harbor water woes loom for Michigan cities

- Michigan is spending big on infrastructure. Its problems are even bigger.

In March, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the state Legislature negotiated and passed a $4.7 billion infrastructure package that allocated federal funds that Congress had appropriated in the last two years in the American Rescue Plan Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The package contained more than $1 billion for drinking water improvements and $712 million for sewer, stormwater, and septic system repairs. Included in the drinking water allotment is $325 million to replace lead service lines.

People interviewed for this project universally acknowledged that the federal infrastructure bill was a once-in-a-career opportunity to reverse course on underinvestment and begin the task of addressing long-standing problems.

This is the first in a new project, Water’s True Cost, by the Great Lakes News Collaborative that will explore the consequences of neglect, the many ways communities are addressing them, and the effects of new water system investment in Michigan. Funded by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, the collaborative’s four newsrooms — Bridge Michigan, Circle of Blue, Great Lakes Now, and Michigan Radio — will report on how state agencies, local governments, and residents can chart a new course for system resilience and service affordability.

Though the costs are enormous and success is by no means assured if upgraded assets are not maintained, for the first time in decades Michigan is addressing systemic challenges in delivering drinking water and cleaning up wastewater that local and state officials and taxpaying residents have been unable to resolve. The project found that the pieces of a new quilt in Michigan, one that reverses the infrastructure decline of recent decades, are starting to align:

- At the direction of the state, utilities are tallying their assets and writing proactive management plans that reduce future costs.

- Communities are drafting affordable water programs and lobbying for state and federal assistance to supplement them.

- Regional bodies are working to coordinate investments and collaborate across political jurisdictions.

- With $350 million in state funding and $100 million in federal funding, 90 percent of Flint’s lead lines have been replaced, part of a state goal to remove all lead service lines by 2045.

- The state allocated $63.6 million to replace lead lines and address other infrastructure needs in Benton Harbor.

At the same time, Michigan communities must contend with financial and regulatory shortcomings that will slow progress if not addressed.

- The federal infrastructure bill is far too small to respond to all deficiencies. Already there is evidence that low-income Michigan households are stressed by high water costs.

- Playing catch-up after all these years will be costly. Even though water bills are rising fast, revenues are still not enough to keep pace with long-term operation, maintenance, and capital needs.

- The state lacks a central repository of information about system size, water production and rates. In fact, Michigan lacks virtually any authority to oversee water systems’ financial health.

- Many rural water districts are relying on distribution systems that have not been updated for decades, due to lack of funds or no political will.

- Michigan has no comprehensive plan to deal with the estimated 300,000 failing septic systems that are polluting the state’s lakes, streams, and groundwater.

Functioning water and sewer systems are a collaborative venture between federal, state, and local agencies and the people in the communities they serve. Provisioned with the materials for change, agencies and communities now need to put the pieces in their proper place.

The Bill Long Ago Came Due

The challenge is immense. From Ishpeming and Marquette to Bad Axe and Detroit, water infrastructure needs are extensive — and failures are magnified. A 48-inch water main in Oakland County ruptured last November, producing a gusher of water adjacent to 14 Mile Road that closed schools and led to several days of boil-water advisories. In Traverse City, heavy rains and high groundwater levels in the last two years contributed to sewage spills that fouled the Boardman River and closed popular beaches along West Grand Traverse Bay. In the state’s southwest corner, Benton Harbor residents have churned through pallets and pallets of bottled water while waiting for toxic lead service lines in the majority-Black city to be removed.

Beyond these headline incidents, city managers confront a constant backlog of maintenance and replacement needs for public works that are, in some cases, well past retirement age. The project found numerous examples of expensive and old water delivery and treatment systems built to serve communities that are much smaller than they once were and robust 20th century industries that no longer exist.

It’s a lot to undertake. Michigan’s local governments and 1,383 community water systems must complete the necessary work without saddling residents, especially those in rural and high-poverty areas, with crushingly large water, sewer, and drainage bills that result in detrimental health, economic, and social outcomes. A historic federal water infrastructure investment of more than $50 billion over the next five years is poised to alleviate some of the burden. But that national outlay is far too small to fix all festering problems in every state. Already there is evidence that certain Michigan households are breaking under the strain of high water costs.

A comprehensive University of Michigan study last year found that water bills, when adjusted for inflation, roughly doubled statewide between 1980 and 2018. The effect was even more pronounced in large cities like Detroit and Flint that lost population after the 1960s as industries moved jobs overseas and white residents decamped for the suburbs. In all areas, families at the bottom of the economic ladder suffered the most. High water costs, according to Noah Attal, a study contributor, are not bound by geography.

“It is everywhere,” Attal said. “Everywhere in the state, you'll find a community center really struggling, either because of high water costs, or because of poverty.”

Altogether, the size of the response needs to match the breadth of the problem.

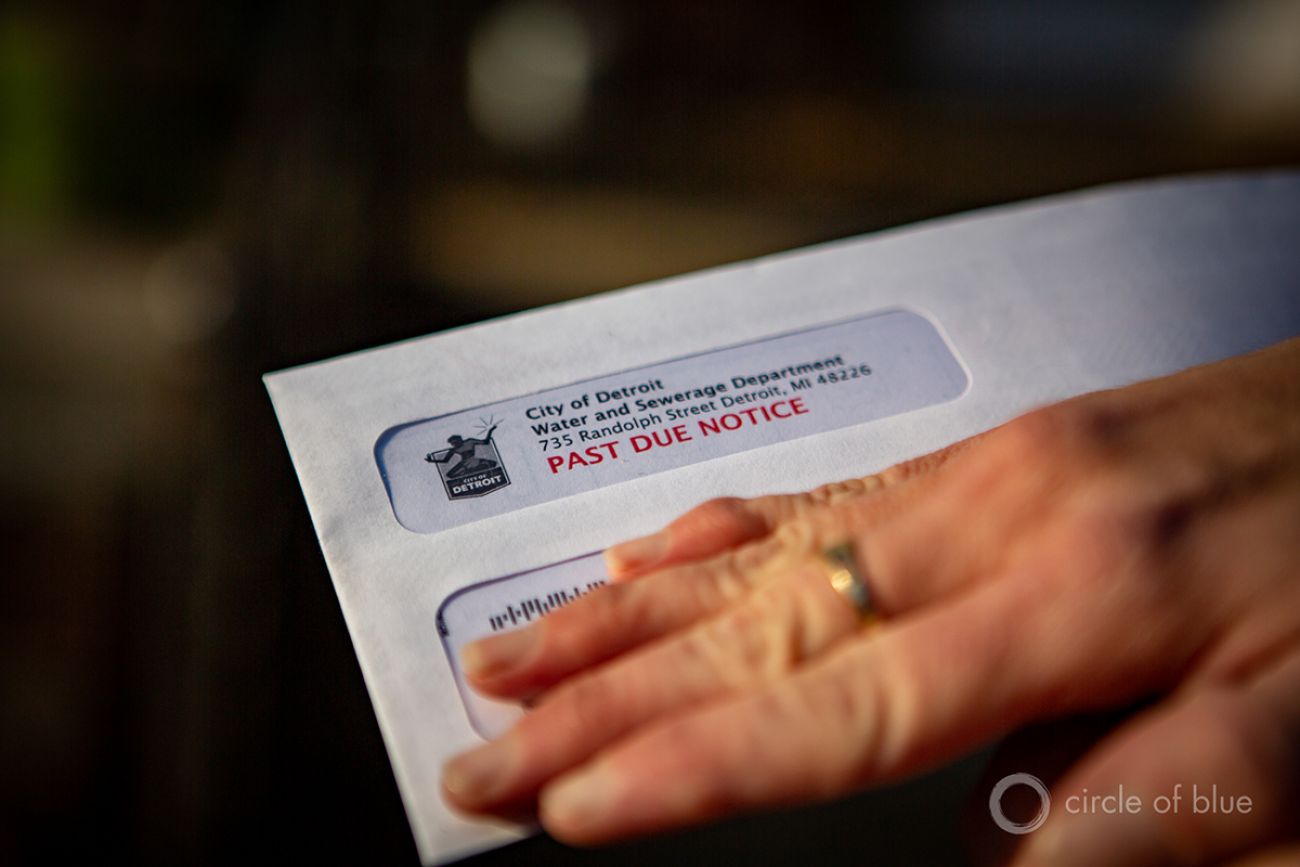

Past failures of management and infrastructure in Detroit, Flint, and Benton Harbor are evidence of how the human relationship with water in Michigan has gone disastrously wrong. Children poisoned by lead. Homes and highways flooded in downpours that are growing more intense as the planet warms. Water shut off to tens of thousands of residents behind on their bills.

“This isn’t isolated to one community or another,” Gov. Whitmer said in an interview with WXYZ last November as she stumped for water infrastructure spending. “This is a systemic issue all across our state.”

Fixing A State of Disrepair

The 21st Century Infrastructure Commission, convened by former Gov. Snyder found generations of deferred maintenance and a landscape of sewage spills, failing septic tanks, deficient bridges, inadequate broadband, and increasing flood damage. Local and state spending on capital projects in Michigan — the sort of projects meant to remedy these ills — steadily declined, dropping from 2.14 percent of GDP in 2002 ($9.3 billion) to 1.35 percent ($6.1 billion) in 2016, a total that placed the state 49th nationally, behind only New Hampshire.< p/ >

Playing catch-up after all these years will be costly. Even though water bills are rising fast, revenues are still not enough to keep pace with needs. The Southeast Michigan Council of Governments, for instance, estimates that one-third of the water infrastructure in the seven-county region is in poor condition. To bring all the water, sewer, and stormwater pipes up to good or fair condition, at least $3.5 billion annually would be needed through 2045. These are the mundane assets that are the backbone of a water system but largely hidden from public view — unless they break. The pipe repair estimate does not include improvements to other system components like treatment plants or pump stations.

Southeast Michigan encompasses Wayne and Oakland counties, where urban centers have struggled with high water costs for decades. The University of Michigan study found that Pontiac, Detroit, Highland Park, River Rouge, Hamtramck, and Flint, which is in nearby Genesee County, have among the highest water costs in the state — compared to income minus basic expenses — for people in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution.

That outcome is rooted in the demographic and industrial decline of those cities and the deteriorating infrastructure that poorer remaining residents had to sustain. But even the younger, wealthier suburbs that grew as these cities shrank are not immune to the long-game demands of infrastructure maintenance and repair.

Mark Vanderpool, the city manager of Sterling Heights, a Detroit suburb, explained that the city is in the midst of a $12 million project to replace all its water meters. Compared to the city’s water system needs, he noted, that effort is the tip of the spear.

“There’s tens of millions of dollars more in infrastructure that is required in Sterling Heights,” Vanderpool said during a Michigan Municipal League Foundation webinar. “And in Sterling Heights, we have a relatively newer system.” The city is also wealthier than the state average, with less than 10 percent of residents in poverty. “We don’t have some of the challenges that older communities have in Michigan, with lead service lines and the like. Nevertheless our needs are really massive and daunting to say the least. Trying to utilize and access every conceivable resource available is critically important if we’re going to continue to have cost-effective water rates for our residents.”

An Immense Shift in Opportunity

The good news is that there is more attention than ever before to these issues, what Janice Beecher of Michigan State University called a “critical mass” of task forces, working groups, advocacy organizations, and funding assistance. At the state level, the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy formed the Office of the Clean Water Public Advocate in 2019 to field and investigate citizen complaints about water and sewer failures. The Water Asset Management Council, an expert group established in 2018, is carrying out a legislative mandate to gather data on the condition of municipal water, sewer, and stormwater pipes. It received its first data submissions earlier this year. The Department of Health and Human Services, meanwhile, is incorporating water access into its current three-year strategy for health and equity.

Trade associations, academia, and local governments are also involved. Last fall, the American Water Works Association, which represents utilities, launched a six-month series of presentations and conversations on water affordability that will culminate in a one-day summit on May 12. The University of Michigan completed its statewide analysis of water affordability in December. The Michigan Municipal League Foundation developed a toolkit for assisting disadvantaged communities in applying for federal infrastructure funds. The Southeast Michigan Council of Governments formed a water infrastructure task force this year to coordinate investments in the region. With the help of a state grant, Oakland County, a member of the task force, brought together community groups to develop water affordability plans for Pontiac and Royal Oak Township.

Communities will not achieve those goals by following tattered playbooks, said Sue McCormick, former CEO of the Great Lakes Water Authority and a current member of the Water Asset Management Council. She emphasized that the next path is carved out of collaboration — not only between governments, but also within departments. Road projects should be coordinated with water main replacements. Communities, rural and urban, ought to band together on regional projects. The objective is controlling costs.

Where they are in place, cooperative agreements offer much promise. Jim Nash, the Oakland County water commissioner, extolled the savings from a joint stormwater project with Detroit. Oakland will send more of its excess flow to Detroit during rainstorms for treatment, eliminating the need for an $80 million expansion of its own system. In return, Oakland will invest $30 million in storm-buffering green infrastructure in Detroit.

“Both of us together are going to be saving money and both of us together are going to be producing much cleaner water into the environment once we're done with this,” Nash said. “So everybody benefits.”

Even though the opportunity is present, beneficial outcomes are not assured nor will they be easy to achieve. What’s holding the process back is the sheer number of municipal governments in Michigan, political squabbles between jurisdictions, and a lack of data, especially for rural areas and tiny systems that serve mobile home parks, which have some of the most severe water quality challenges.

Once pipes are replaced, the next step is civic repair. Rebuilding community trust, after years of inadequate service or foul tap water, is just as difficult, perhaps more so, than the engineering work. Sylvia Orduño, a community organizer for the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, which advocates for low-income households, sees residents buying bottled water even after their lead pipes are removed.

“How is it that all of this money and investment is being done and yet we still have people that don't trust the drinking water right here in a Great Lake state?” Orduño asks.

City managers and state officials have a delicate task in front of them, said Sara Hughes, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan who studies water infrastructure. Not only must they weigh present demands and take care not to maintain public support by not surprising residents with high bills. They must also consider how those expensive assets will fare decades down the road as a warming planet inflicts unaccustomed strains of heat, drought, and deluge.

“If we are making these big investments, we need to make sure we're thinking about how they perform under a kind of new climate regime,” Hughes told Circle of Blue.

To Hughes, there is less discussion about climate resilience than there should be. And she would hate to see the opportunity wasted.

“Ten years from now, it would just be such a shame if we're still not prepared for large flood events, or new runoff patterns to our source waters, or the effects of high heat days on our infrastructure,” she added.

Big changes won’t come about all at once, though. Spring marks the beginning of construction season in Michigan, and a $7.8 million water main replacement in Pontiac is an indication of the near-term direction the state is headed.

About a mile west of downtown, at an intersection flanked by modest brick homes and apartments, heavy machines perch at the rim of an open pit, their yellow-vested operators pausing mid-day for lunch.

By the end of a chilly March afternoon, the new water main now visible in the dirt beneath Liberty Street and Murphy Avenue will be buried, and the excavators and bulldozers will have moved down the block, ready once more to split open the cocoa-brown earth and replace another section of worn out pipe.

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!