In Frankfort, small homes offer big hope in northern Michigan housing crunch

- Short-term rentals are eliminating homes for year-round workers in tourist towns like Frankfort

- One solution is coming from a new land trust, which by end of summer will start selling four new houses to middle-income earners

- A lack of housing is contributing to an employment crunch in northern Michigan

FRANKFORT — A grid of pink surveyor flags on a building site signals the high stakes for this Lake Michigan community as it confronts a problem plaguing tourist towns throughout the state: housing affordability.

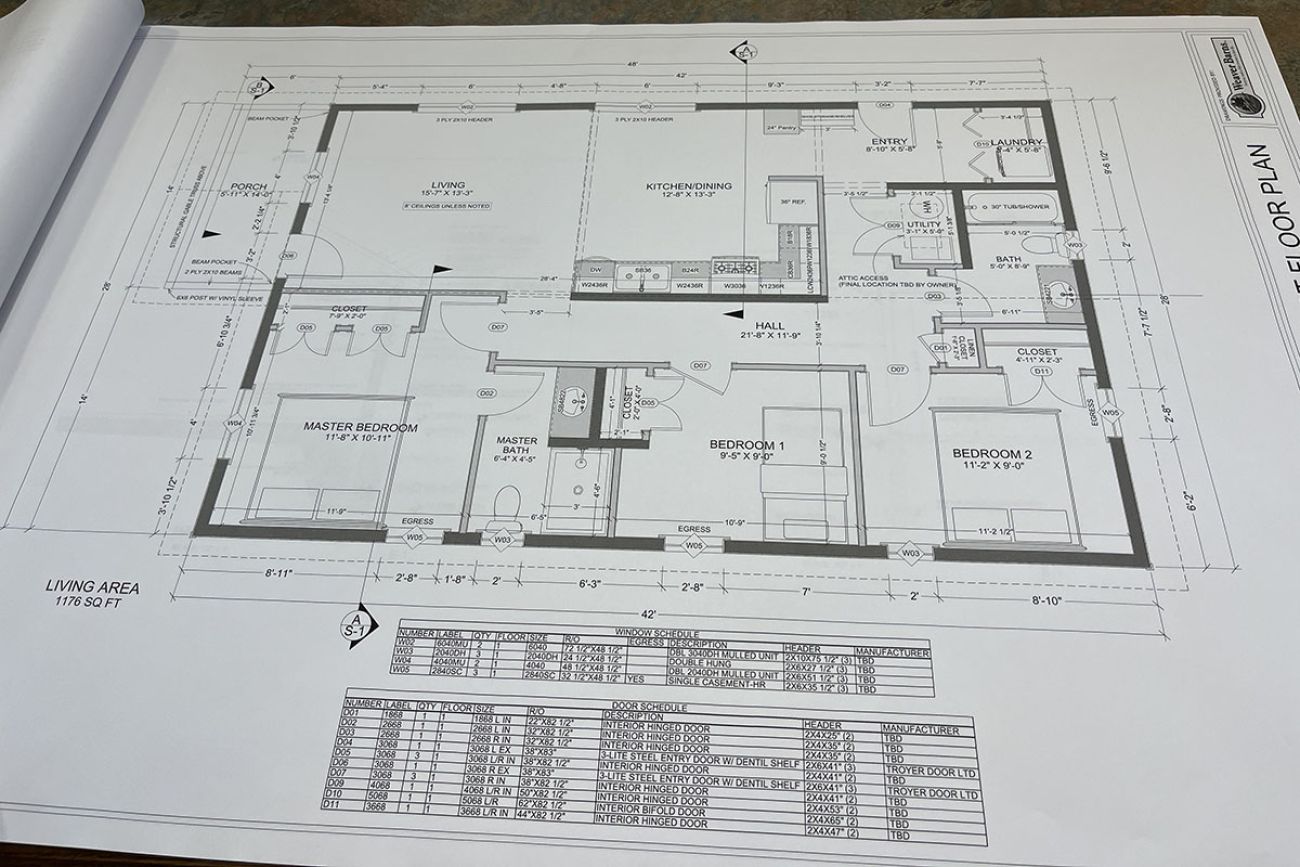

Soon, the shells of two cottage-style modular panel houses will be set on new foundations on half of the cleared land. Amish workers from Clare will install cabinets, trim and other finishes. And, within months, two more ranches are planned

Frankfort, which is near Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, is like many Michigan shoreline communities. It’s popular, tourist-heavy in summer and trying to provide year-round services to a community where its 430 or so homes are increasingly either seasonal or short-term rentals.

Related:

- Up North businesses are buying housing just to lure summer staff

- Michigan’s housing crisis has spread to Alpena. How $100M can help.

- Rent or buy? No easy answers amid high Michigan home prices

Local officials have spent years trying to expand homeownership for year-round residents, and they’re celebrating the new houses that will be built with a mix of state and local funds. The 1.5 bathroom, three bedroom ranches are just less than 1,200 square-feet and will cost $197,000 apiece to build. They will sell for about $175,000, below the $750,000 median price of the last five homes sold in Frankfort.

Four houses are a small fraction of those needed for year-round Benzie County residents or statewide, where housing officials estimate the state needs 190,000 more “missing middle” homes for those with mid-range incomes who neither qualify for housing subsidies nor can afford skyrocketing housing prices.

“It’s a small number, but for communities like us, it’s huge,” said Josh Mills, the city superintendent.

“We’re really hoping some small families are able to take advantage of this and that we can keep people working in our Main Street corridor.”

The houses are being built by the Frankfort Area Community Land Trust, a nonprofit formed in 2021 to advance homeownership in the city of 1,300, said interim executive director Liz Negrau. The effort complements the recently established city Housing Commission’s four-year focus on increasing year-round rental housing.

About $240,000 in grants from a new $100 million Michigan State Housing Development Authority program will help to fund the construction.

Launching a building effort so quickly was essential to the land trust’s founders, Negrau said. Having few homes available for year-round residents “starts to chip away at the community,” Negrau said.

Year-round workers who can’t find housing in Frankfort, the largest city in Benzie County, will commute, driving 45 minutes from smaller towns, she said. Their children don’t attend local schools. The seasonality of businesses grows, with many closing after summer’s peak months when the county’s population increases by 121 percent. And with fewer year-round services, those who already make the city their permanent home also have to travel farther, while feeling more isolated in winter.

The reasons for the housing shortage are complex. Single-family home construction for median income earners has lagged for years in Michigan, starting in the Great Recession and continuing through recent 40-year peak inflation, while costs for building supplies and lots push builders into higher-price construction.

On the Lake Michigan shoreline, housing stock is increasingly turned into expensive vacation or short-term rental properties.

In Benzie County, about 60 percent of houses are occupied by vacationers in summer. That drives prices higher than households earning under $100,000 can afford — particularly if they’re financing now that interest rates for 30-year mortgages average over 6 percent.

At the same time, new construction isn’t likely to pick up this year, according to forecasts. Michigan building permits for all residential styles, including apartments, were 26 percent lower in February than a year earlier, when 1,836 were filed.

In Frankfort, the situation keeps getting worse, with businesses already struggling to find housing for seasonal workers. Now, Mills said, they’re increasingly wrestling to fill year-round jobs, raising questions about the town’s economic future.

“The biggest issue is the lack of affordable housing,” he said.

Todd Bruce, owner of A. Papano’s Pizza and a Land Trust board member, said some Frankfort employees “couch surf” with friends and family because they can’t find housing but need to keep their job.

“We now have businesses that are serving mostly the transient tourist crowd,” he said.

“There are people who would like to open more businesses and be open longer, if they had employees who could staff them,” he said. “But we don’t have them.”

Funding from the state

The land trust’s first stab at a solution is being watched across the region to see if it can be replicated, said Mills, the Frankfort supervisor and a board member at Housing North, a nonprofit focused on housing across 10 counties in Michigan’s northwest Lower Peninsula.

Community land trusts are a newer option for financing home development, with land ownership retained by the nonprofit. Another one in northwest Michigan also recently formed, Peninsula Housing in Leelanau County.

In Frankfort, while the buyers will own the house, the land ownership will remain with the land trust. And future sales will require sellers to price at 25 percent under market value at the time.

“What that does is it retains that home for our workforce in perpetuity,” said Jay White, who is active with the land trust, a city planning commissioner and retired Realtor.

The Frankfort program was helped by the Michigan State Housing Development Authority, which launched last year with $50 million from the state and a goal of adding 1,500 homes for middle-income earners. In January, the program received another $50 million.

Kathy Evans, program manager for Missing Middle Housing Program, said the money is from the state’s share of the $1.9 trillion federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding. Of about $11 billion that came to Michigan, much of it went to municipalities and schools, but that still left hundreds of millions of unexpected money in state hands.

The program’s first round of funding for nonprofit developers allocated $15 million, and about $9.5 million was awarded, including $240,000 to Frankfort’s land trust. Combined, the awards totaled funding for 158 housing units, 121 of them that will be available to buyers.

Many of the units awarded in that round are in west and northwest Michigan, Evans said. Among the accepted grant requests, which will be paid when the project is completed, are 44 homes in Grand Rapids, 24 in Holland and 29 in two areas of Emmet County.

The next round, which will be open to proposals through September 2024, offers $80 million to developers of either for-sale or rental housing, and the nonprofit criteria was removed. The remaining $5 million is allocated for administrative costs, Evans said.

This round is likely to be more popular since “there are a lot more people who can apply,” Evans said.

So far, the number of rentals exceeds for-sale homes in the second round. The building pricing pressures continue in Michigan, Evans said, and “seasoned developers lean toward rentals.”

Most of the state money is divided into 15 regional pools, reflecting the state’s goals of sending 30 percent of the money to rural areas and funding projects in all areas of the state.

So far, only one area has no completed applications: The Lake Huron shoreline around Alpena and Oscoda. Some have just one, including Washtenaw, Oakland and Macomb counties.

The state has many programs for people with low incomes — those who earn less than the Area Median Income (AMI) in Michigan’s 83 counties. That amount varies by region: In some counties, a family of four making $60,000 is low-income, while it’s closer to $90,000 in Washtenaw County.

High demand, few homes

White, of the land trust, said real estate agents struggle when working with local families to buy a year-round house.

“They’ve said there’s no way to do it,” he said.

A 2020 market study by Housing North said that Benzie County could use 703 new housing units that year — and that 248 of them should be for sale and priced at $200,000 or less to meet demand.

Of those, Frankfort needed 26, but Mills said new construction in that price range hasn’t happened in years.

In Frankfort, buyers will have to earn between 60 and 120 percent of the area’s median income of about $80,000, or roughly $70,000 to $100,000 for a family of four. The state grant requires that a buyer also qualify both for a conventional mortgage and keep total housing costs to 30 percent or less of their income, White said.

Grants from Benzie County and the city are supplementing the state funding, and other items — like trees — are being donated. Local construction workers also are offering low bids because, Negrau said, “they understand what we’re up against.”

“What we’re going to pay for the house is less than what they will appraise for due to a lot of the generosity of the community,” she said.

The city itself also has many other plans taking shape to expand housing options, said Mills, the city superintendent.

Among them are building 12 two-bedroom apartments on city-owned land in partnership with a nonprofit developer. Also aided by $600,000 in MSHDA funding, the apartments will rent for below $1,000 per month, including utilities.

Beyond that, Mills said, the city is studying its zoning to see if it can increase the number of rentals for seasonal worker use, too, including trying a plan to lease spaces to businesses who can park travel trailers on city property for workers this summer. It also initiated a short-term rental ordinance to cap them at 10 percent of housing stock.

But for now, Frankfort is celebrating the four new houses it’s adding to the community.

Seven potential buyers have contacted the nonprofit that will evaluate applications, and more may be added to the list.

For the people working in the community and hoping to buy a house, “we’re holding these open for these families,” White said. “We’re saying these four homes that we’re building are for our workforce.”

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!