Farmland near Grand Ledge could be Michigan megasite for high-tech project

- 1,400 acres near Grand Ledge are taking shape as a ‘megasite’ as Michigan races to cash in on high-tech manufacturing

- The semiconductor industry may target the assembled property, with MSU being a significant property owner

- Some neighbors in this rural community are fighting the move and hope to get more answers from officials what might be built on the site

A rural area near Grand Ledge is gaining momentum as Michigan’s leading contender for the state’s next massive high-tech jobs offering.

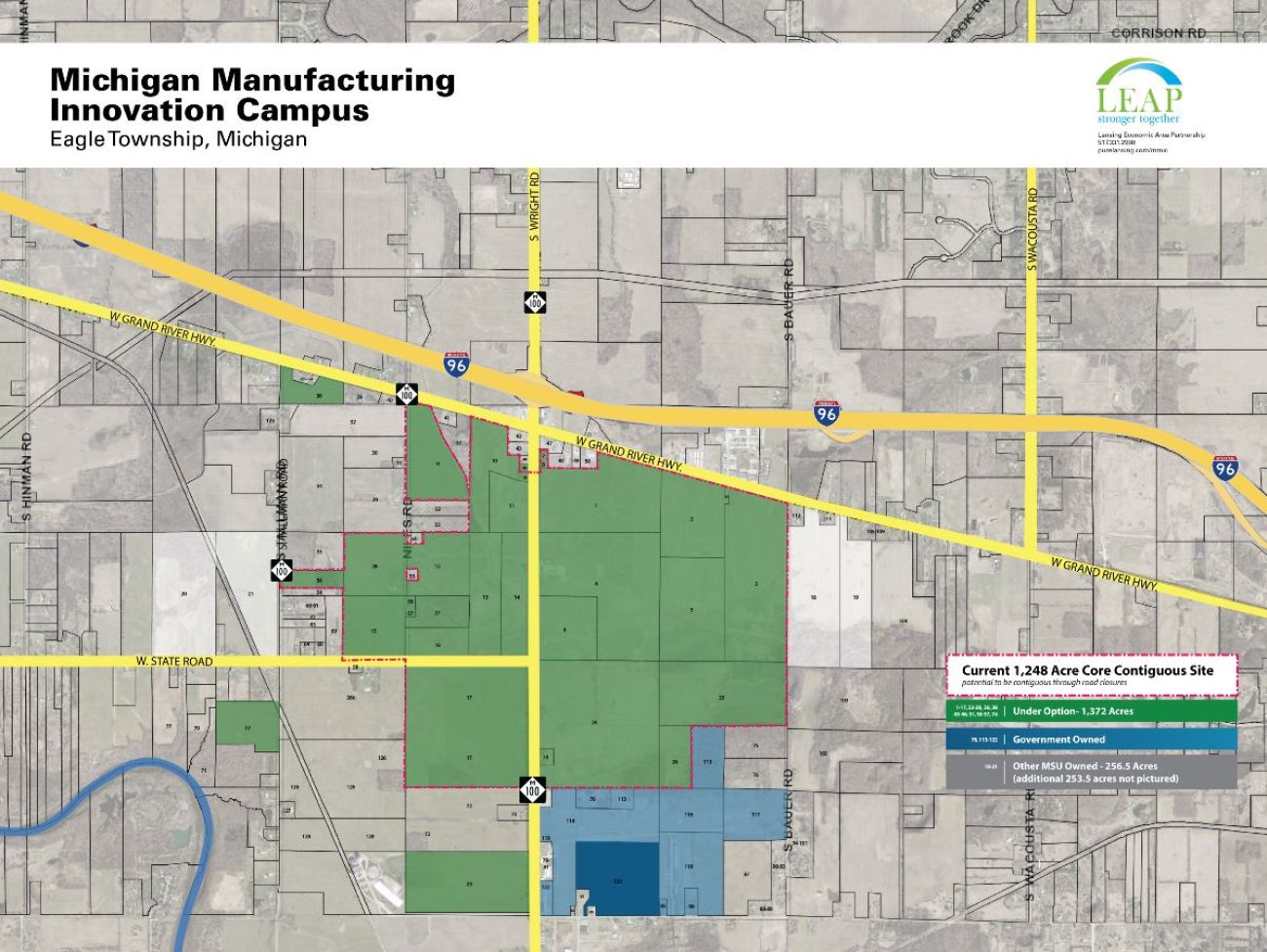

Regional economic developers have assembled about 1,400 acres in Eagle Township — including at least hundreds of acres owned by Michigan State University — as they market it across the U.S. to site selectors seeking huge tracts of land for electric vehicle battery and semiconductor production.

“I think it’s America’s best megasite,” Bob Trezise, president and CEO of the Lansing Economic Area Partnership (LEAP) economic development group, told Bridge Michigan.

Related:

- How Michigan could benefit from Washington’s $76B investment in microchips

- Michigan invests $5M to turn 3 properties into 'build-ready' mega sites

Chip-makers and battery manufacturers “are looking to make 50-year decisions about where to locate these massive plants, which can change an entire state’s economy just by landing one of them,” Trezise said.

The site, which LEAP calls the Michigan Manufacturing Innovation Campus, could reach 1,600 acres, making it among the largest potential industrial development sites in the state if rezoning and other authorizations are approved.

Unclear so far is how close the assembled property, which is largely farmland, may be to any potential deal.

While any large-scale industry could be considered for the megasite, “a lot of the focus … has been around the semiconductor industry,” said Keith Lambert, chief operating officer for LEAP.

MSU is among about two dozen township property owners inking deals to sell the property to a purchasing entity of LEAP, which Trezise said has spent millions of dollars so far assembling the land from individual owners with the aid of a commercial broker from CB Richard Ellis.

The move comes amid intense competitive pressure across the U.S. as communities vie for the massive high-tech factories that will fuel manufacturing and fulfill goals for “onshoring” — the moving of manufacturing to the U.S. The effort was started to address the critical supply chain shortages related to the microelectronics — the so-called “brains” behind much of both industrial production and consumer devices.

Michigan has been poised to gain a share of the semiconductor market since President Joe Biden in August signed the $280 billion Chips & Science Act with $50 billion earmarked for semiconductor manufacturing plus research and development, including $2 billion dedicated to making automotive-grade chips.

The program “will create and protect tens of thousands of jobs, (and) bring the supply chain from China to Michigan,” Gov. Gretchen Whitmer said at the time as she launched a statewide push into the chip industry.

However, one requirement for giant factories that has been a stumbling block for economic developers in Michigan is that companies want properties of at least 1,000 acres that are ready for construction and with available infrastructure — such as access to copious electricity, nearby commercial transportation and municipal water supplies.

Meeting all those requirements within quick-fire windows of opportunity is difficult in the private sector, Trezise said. And Michigan has not prioritized the availability of large sites over many years.

“These companies seem to be requiring that these large sites are essentially publicly controlled,” he said. “Because that obviously reduces their risk.”

The Lansing-area project has been in the works for over a year, though recent steps in the public planning process to allow a rezoning have increased its visibility, including among neighbors who oppose it.

LEAP was among three groups that applied for $250,000 site readiness grants last March from the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. The money was awarded in August by the Michigan Strategic Fund, the public funding arm of the MEDC.

The funding source was created with state approval of the Strategic Outreach and Attraction Reserve in late 2021, when the bipartisan legislation was proposed to make Michigan competitive with other states — such as Kentucky and Tennessee, which each landed Ford Motor Co.’s massive new EV battery sites — that were already investing in potential large-scale sites.

Information on the state’s total investment in the Eagle Township site assembly was not available Friday.

Taking shape

Eagle Township, population 2,700, is in the far southwest corner of Clinton County, just north of Grand Ledge and connected to the greater Lansing area and the south-central portion of the state via I-96, which crosses near its northern border.

Visitors to Eagle Township see expanses of farmland and large-lot single family homes, all of which are just a 20-minute drive from the state capitol in Lansing.

Sometime in the next week, visitors are also likely to see yard signs on the main roads — like at West Grand River and Wright Road at the highway interchange — displayed by residents who’ve learned of plans for the megasite and don’t want it there.

Cori Feldpausch, who lives a few properties from the western-most block of land, said she’s been asking Eagle Township officials and others — including the MEDC — for answers about what is planned for the site.

After hearing that officials can’t talk about it due to non-disclosure agreements, she said she got angry.

“Not everybody is for this,” Feldpausch told Bridge. “This is our community and we have the right to say what we want in our community.”

Feldpausch recently started a Facebook group to educate and unify township residents who don’t want massive development to replace the rural atmosphere. She’s working with a core group of about 10 township residents, she said and, in addition to gathering hundreds of yard signs, they started a petition on change.org, which roughly 650 people had signed by late afternoon Friday.

“While it’s easy to look at the positive economic impacts a large industry would have on both the local and state economies, it would be negligent to turn a blind eye to the negative impacts a megasite would have on the local community,” the petition says.

“Changing 1,400 acres of farmland to industrial use is not ‘reasonable growth,’” it added.

LEAP’s marketing for the property calls it “flat, clean land with all due diligence complete or underway.”

The land is adjacent to I-96, and within 90 minutes of four international airports. A non-primary airport owned by Grand Ledge is located at the southern end of the proposed megasite.

LEAP said local municipalities are “engaged and in full support.”

Eagle Township Supervisor Patti Schafer did not respond to a Bridge call on Friday, but a report from December in the Lansing State Journal said officials in Clinton County — which contracts with the township for planning services — has hired consultants Giffels Webster of Birmingham to explore rezoning.

Many members of the group organizing to oppose the plan said they are disappointed that MSU has joined in the megasite effort. Some remembered Dave and Betty Morris, who donated their land to MSU in 2005.

The property, about 1,300 acres, was to be leased for agricultural use for 25 years, according to a report in Michigan Farm News, but MSU spokesperson Dan Olsen told Bridge the deal doesn’t have strings attached for what its eventual use will be if the university sells it.

However, under the deal, proceeds from the sale of the MSU land would have to support four agriculture-related endowments named after the Morrises, Olsen said. And an eventual transaction would have to be approved by the MSU Board of Trustees. Unclear is how much of the property is included in the megasite plans.

Olsen said he could not comment on any specifics related to the potential use of the land, but he noted that “certainly the chip manufacturing industry is something that is a top focus for the state and nation.”

He said MSU is “committed to utilizing this property for large-scale economic development opportunities if they align with our strategic priorities and mission."

Focus on chips

Whether or not chips are the focus of the Eagle Township megasite, both the state of Michigan and MSU are building their profile in the industry.

One month after LEAP made its proposal to the MEDC in March for site preparation funding, then-Michigan State University President Samuel Stanley was invited to Columbus, Ohio, to talk about semiconductors.

Ohio State University called on MSU and other regional schools to form a Midwest network, MSU said, to “bring the semiconductor and microelectronics supply chain to the Midwest and expand supply chain ecosystems.”

At the time, Columbus was still celebrating news from last January that Intel Corp. — one of three leading global chip manufacturers — had chosen a site just outside of Ohio’s capital for a pair of $20 billion chip factories.

MSU announced that it was joining the collaboration with 11 other colleges from several states on August 4.

The chips move by MSU was one among many in Michigan last year. They include expansions by SK Siltron, a semiconductor technology company, which is more than doubling its manufacturing capacity by building a second, $300 million facility near its current one in the Great Lakes Bay region. Hemlock Semiconductor also started a $375 million expansion in Saginaw County’s Thomas Township.

Then, in November, Whitmer and the MEDC formed what they called a Semiconductor Talent Action Team to identify “semiconductor-specific curricula and R&D investments” to help Michigan win semiconductor investment.

MSU also continues its years-long research into semiconductors by planning a new Engineering and Digital Innovation Center on its campus in East Lansing, and is launching a new degree program in engineering technology that, it said, “is aligned with the semiconductor industry expansion in Michigan.”

Meanwhile, in December, Intel was listed by the state as Clinton County’s top job-poster, with 225 openings. Unclear is what drove that.

“There are no new projects in Michigan that we are announcing,” an Intel spokesperson told Bridge this week.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!