Wall built to segregate Black Detroiters reclaimed as historic site

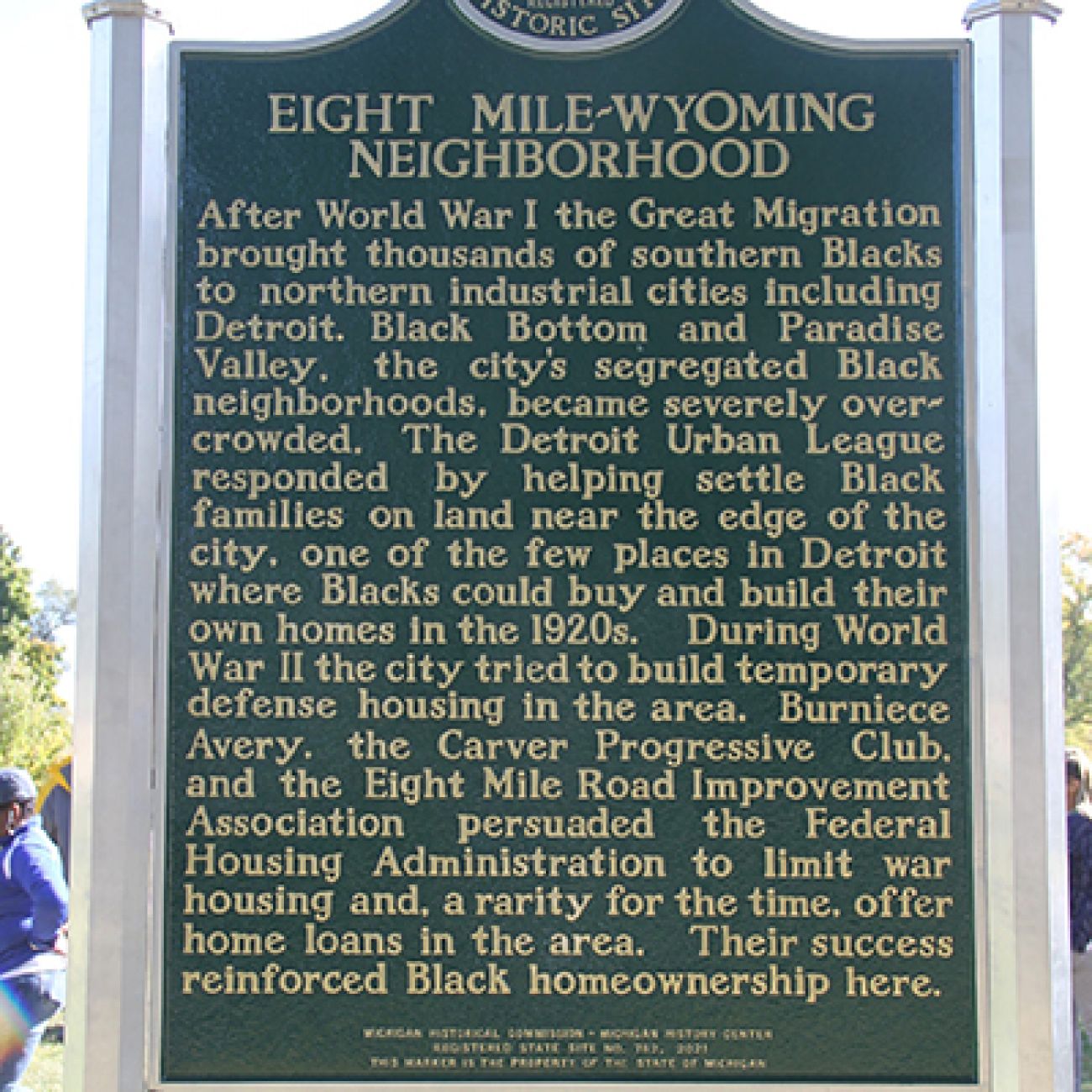

As a child, Elizabeth Moore never questioned why a graying concrete wall stood at the edge of her neighborhood playground near Eight Mile and Wyoming.

Moore, who moved back to her former neighborhood after the death of her father 20 years ago, said she remembers playing a game with other kids to see who could walk furthest along the six-foot-high wall – not knowing at the time it was built to physically separate Black Detroiters from housing developments exclusively catered to white families.

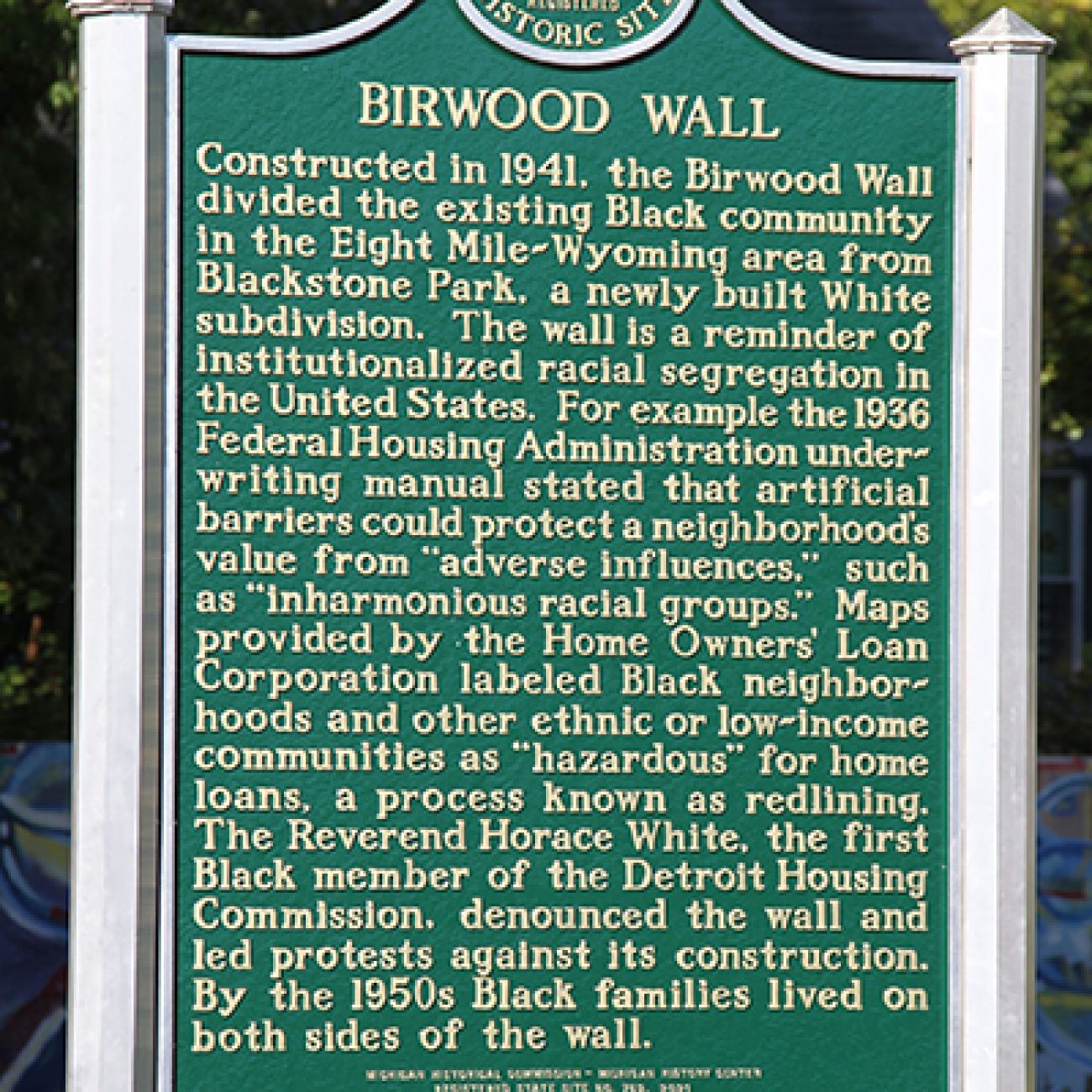

There will be no mistaking the significance of the Birwood Wall, also known as the Wailing Wall or the Eight Mile Wall, for anyone living in the area today. A new historic marker unveiled Monday describes the wall as the embodiment of how government policies and private institutions conspired to enforce the segregation of Black Detroiters.

Related: Built to keep Black from white: The story behind Detroit’s 'Wailing Wall'

“I had no idea the magnitude of this wall,” said Moore, one of a few dozen residents in attendance at the Monday event. “I’m glad to know it now. I’m saddened by it, but that’s the world we live in. We have more walls than this to get over. This is a physical wall, but you know, there’s a whole lot of other walls we have to break down or change.”

The Birwood Wall was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2021 along with four other Detroit sites noted for their association with the Civil Rights movement and the experience of Black Americans. Jamon Jordan, the City of Detroit’s first official historian, said the wall is an important reminder of America’s racist past, worthy of preservation and recognition.

“There will be people who will not believe you if you told them there was a segregation wall built in the United States, in the north, in the City of Detroit in 1941,” Jordan said. “They say ‘OK, I can understand that in South Africa, but not the United States.’ Having this wall here helps to make that story clear. Now it’s pretty known that segregation was a national phenomenon, and the federal government was highly involved in housing segregation. This wall is evidence of it. That’s why the wall is still important, and I would argue, ought not be destroyed.”

The Birwood Wall was built by real estate developer James T. McMillan to keep Black Detroiters out of a new subdivision on the city’s west side, which made it easier to obtain federal loans. At the time, the Federal Housing Authority would not subsidize developments close to Black neighborhoods, and FHA’s underwriting manuals showed a preference for using physical barriers to stop integration.

It worked for a time, but the wall ultimately failed. Black families started moving beyond the wall in the 1950s, thanks in part to the demise of racially restrictive covenants by the U.S. Supreme Court. The ruling came in a case argued by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall on behalf of Detroiters Orsel and Minnie McGhee, who moved into a white-only neighborhood in 1944.

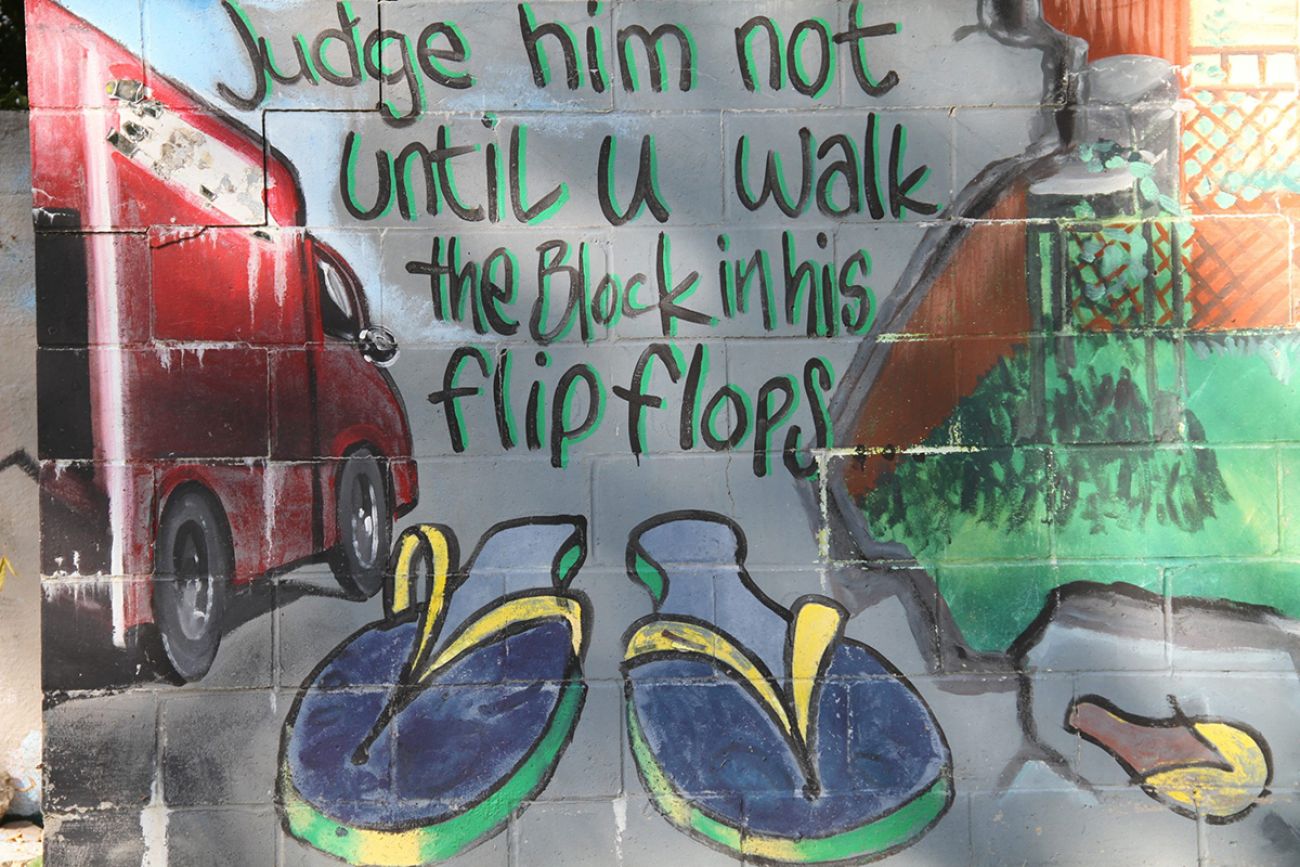

The 2,200-foot-long wall was formerly a blank slate of concrete. But in 2006, Detroit artist Chazz Miller and area residents painted a colorful mural across a stretch of the wall depicting scenes from Black history, like Sojourner Truth leading children through the Underground Railroad, and images reflecting life in the Eight Mile-Wyoming Neighborhood.

Jordan said the wall has been reclaimed by Detroiters and that the mural symbolizes the Black community that lived in the Eight Mile-Wyoming area before the wall was built and will persist long after.

“This mural tells the story of children who live and grew up in this community,” Jordan said. “It tells a story of the actual community that’s here, not just the racist policy of the developer and the federal government. We’ve got both stories – the story of an active community living here and the history of the building of this wall to symbolize racial discrimination.”

Moore said it was people like Teresa Moon, who has lived in the area for more than 60 years, who first exposed her to the history of the Birwood Wall. Moon moved into the neighborhood with her family in 1959. Moon said she was “subjected to seeing this wall every day” while growing up, but also didn’t learn about the truth of the wall until much later in life.

Today, Moon said she’s driven to make sure the “love and the commitment and the strength that was passed down from the people who had the tenacity to keep this community together never dies.” Moon, an activist and community organizer, helps maintain a park surrounding the wall and serves as an unofficial historian for the neighborhood.

“It’s been 81 years since (the wall) was erected; there are new barriers,” Moore said. There are new red lines. There are new injustices. There are people underserved. A lot of those people live in my community and that’s what I represent. We say ‘Eight Mile for life.’ It means a lot to us to have grown up in an area that has just recently been designated as a historical area.”

Roy McCalister Jr., a former member of Detroit City Council, said the wall serves as a reminder and a call to action to address housing issues affecting the city today.

“Affordable housing is still an issue,” McCalister said. “This issue is almost like it continues on but just in a different frame. You’re looking at the past and the present, we’re still dealing with these issues.”

To be considered for National Register listing, a property must be at least 50 years old, possess historic integrity, and be significant for its association with important people, events or architecture. Detroit is home to many such sites that haven’t been recognized, city officials said Monday.

Mayor Mike Duggan said recognition of the Birwood Wall is “overdue.” That’s why the City of Detroit hired Jordan to serve as Detroit’s historian. Jordan said his hiring ensures “Black stories would be centered” and taught to Detroiters. He’s also part of an effort to bring more Detroit sites into the spotlight, he said.

Michigan’s State Historic Preservation Office received a grant in 2016 to document sites in Detroit that have a close connection to the Civil Rights movement. An advisory board of local historians was formed to recommend locations. More than 100 sites have been identified since the project began and seven sites were added to the National Register of Historic Places thus far.

Last year, the Birwood Wall was added along with New Bethel Baptist Church, the Rosa L. and Raymond Parks Flat, Shrine of the Black Madonna of the Pan African Orthodox Christian Church and the WGPR-TV studio. Brian Egan, president of the Michigan Historical Commission, said the historic markers educate future generations about the country’s complicated history.

“Maybe it’s not always positive, maybe it’s not always something we want to share, but it’s something that reminds us and inspires us,” Egan said.

Egan added the state is undergoing an audit of historic markers “that may not have had a balanced story told” to uplift untold chapters of Michigan’s history.

Duggan said Detroit’s history is closely entwined with strategies to keep Black people out of white neighborhoods.

“When you think it’s ancient history, it really hit me a few years ago when we bought the land for the new Jeep plant off Mack Avenue,” Duggan said Monday. “The deeds to some of those parcels … said on them ‘can only be sold to Caucasians.’ The deed restrictions were still there. They may not have been enforceable, but they’re still on those deeds. We are still recovering from that racial discrimination in this country. We work on recovering from it every day, but we can’t recover from it if we aren’t aware of it.”

Duggan noted the National Register’s recognition of the Ossian Sweet House at 2905 Garland, the home of a prominent Black physician who had to defend his family against a mob of white Detroiters who had violently opposed integration on the city’s east side. Duggan also highlighted Detroit’s role in ending restrictive covenants; the McGhee’s former home is recognized with a historic marker.

Keith Williams, chair of the Michigan Democratic Black Caucus, said recognition is only part of the mission. Williams is an advocate of a city task force being formed to explore how Detroit could provide reparations for Black residents affected by historic injustices.

“Markers are fine, because it acknowledges what has happened,” Williams said. “What would be nice is if they pay the people who were affected by the wall. There are other kinds of walls we don’t want to talk about – the walls of poverty and wealth gaps. How do we take all this stuff and rebuild and repair? The city won’t go any further until they’re acknowledging the pain that was caused by racism.”

Jordan said it’s important to take a hard look at the past, especially at events we may not be proud of today.

“If history doesn’t ever make you uncomfortable, then it’s not really history,” Jordan said.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!