Understanding why Detroit floods and why it keeps happening

Thousands of Detroit residents, businesses, churches, nonprofits, libraries and others will likely need months to recover from the disastrous flooding caused by record rainfall two weeks ago and aging water infrastructure.

It was the second time a so-called 100-year rain event occurred in the past decade. The last time was August 2014. Heavy rains in metro Detroit have caused massive flooding in homes, streets and freeways at least four times since 2016.

The unprecedented amounts of rain are overwhelming an aging public infrastructure.

Related:

- Michigan flood waters, heat may have spiked Legionnaires’ disease

- Reimbursement remains unclear for Detroit’s flood victims

- Detroiters demand solutions after massive flooding

- First person: Dearborn’s devastating flood exposes mistrust, deep divides

- Detroit-area floods mean sewage backups. Fed dollars won’t fix issue soon.

“We clearly can’t go on like this,” said William Shuster, chair of Wayne State University’s Civil and Environmental Engineering Department. “The infrastructure was built for a different time and place, and that’s changed. We are not keeping up.”

To understand the challenges that the region faces, here are various studies, surveys and recent media interviews that provide facts and analysis.

Where Detroit tends to flood

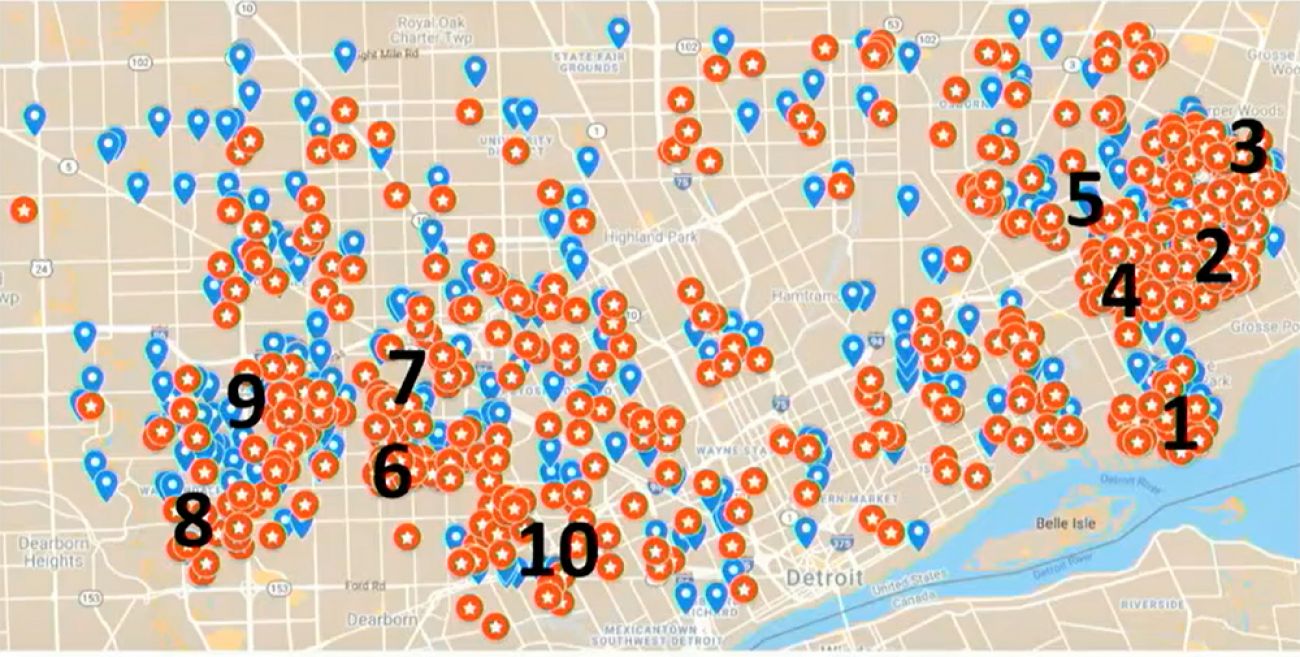

This survey, which should be released by the end of July by Wayne State University and the University of Michigan-Dearborn, shows which parts of the city — from Jefferson Chalmers,on the east side, to Aviation Subdivision on the west — have dealt with recurrent flooding since 2012.

Among 4,667 Detroit households surveyed between 2012 and 2020, 46 percent have dealt with flooding. There is a map showing which areas are more at risk of flooding — and it is strikingly similar to the current maps released by the City showing the hardest hit areas in the current disaster. The map doesn’t name neighborhoods, but shows clusters of streets on the west side, the northeast and lower east side that are prone to flooding.

The report describes the physical and emotional impact many residents deal with long after the water recedes. There’s also a resource guide for various agencies that can provide assistance.

Decades of under investment

Federal investment in the region’s infrastructure went from 60 percent in the 1970s to 10 percent by 2014, according to this June report by the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG). The figures refer to the seven-county region that includes Detroit.

That’s one of the startling figures of how much public investment has dried up over the years, and how much more is needed now and the immediate future, according to SEMCOG.

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer blames climate change and has renewed her push for infrastructure funding. “Now we are seeing the cost of not fixing it,” Whitmer said at a recent press conference on an empty stretch of I-94 that was closed due to flooding. “It would be overly simplistic to use one-time dollars, because this is an ongoing problem.”

The region needs $5 billion annually to get its water and transportation infrastructure up to “good/fair” conditions, SEMCOG estimates. The report examines the aging state of many key components, such as public sewer pipes and water service lines to homes.

“Much of the infrastructure is reaching the end of its useful life,” said Kelly Karll, who analyzes the area’s infrastructure system for SEMCOG, a regional planning organization.

Upgrades are planned. The Great Lakes Water Authority (GLWA) estimates spending an average of $334 million a year on a total 169 projects over the next five years, according to its capital improvement plan released in December. The authority services Detroit and other southeast Michigan communities, including Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties, among others.

The GLWA was created in fall 2014 due to Detroit’s bankruptcy. The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) focuses on the water and sewer systems within the city. This website provides a list of projects it plans for various facilities.

Suburbs versus Detroit tensions

During the record rainfall, two pumping stations on the east side had electrical problems that interrupted the power supply at the facilities. The Conner Creek Pump Station and the Freud Pump Station move water downstream from Detroit, Grosse Pointe Park and Grosse Pointe Farms. Those communities were slammed by flooding.

That caused Macomb County Public Works Commissioner Candice Miller to call for an inquiry into the operation of the Conner Creek station on Detroit’s east side. The facility had similar issues during storms in 2014 and 2016. GLWA, which operates the pumping station, will conduct an independent investigation.

The issue has raised long-standing tensions between Detroit and its neighboring suburbs. Russ Bellant, a retired engineer who worked for years at DWSD, said the incident reveals how the suburbs remain too dependent on Detroit’s aging facilities. Macomb and Oakland counties need to upgrade suburban infrastructures to prevent too much water and sewage flowing into Detroit, he said.

“On the east side, the Detroit-owned sewerage system has flow from Oxford, Rochester Hills and Macomb Township that competes for space at Detroit facilities that serve residents of the lower east side,” Bellant said. “And those Detroit residents are losing,” because the flooding ends up in their neighborhoods.

The same thing is happening on the west side with sewage from western Wayne County and Novi and parts of Oakland county that go through Dearborn and end up at the wastewater treatment plant in Detroit, Bellant contends.

“Again, these sewers are filled with sanitary flow and rainwater by the time they get into Dearborn and Detroit, and they cannot handle the local load,” Bellant said.

Bellant had a sharp exchange with Miller about this issue on the local Fox News program “Let It Rip.”

“We don’t have clean hands in this,” Miller said. “We neglected our infrastructure for years” in Macomb County.

She pointed out that work has already begun by the two counties on a multimillion facility that will reduce flow into Detroit. Miller also pointed out that the county has struggled to get state and federal support for its projects.

Bellant may have a point, but analysts and officials say there is plenty of blame to go around.

“It’s nobody’s fault in particular; we have a huge and expanding service area,” said Wayne State’s Shuster. “Regional cooperation is the way forward. Let’s focus on that opportunity.

“This is an equal opportunity disruptor, destroyer of health, property and morale.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!