Black flight to suburbs masks lingering segregation in metro Detroit

Nearly a half century ago, as Detroit licked its wounds following the violent uprisings of 1967, the national Kerner Commission bemoaned the sad state of segregation in America’s central cities and the housing woes endured by African Americans and the urban poor.

And few regions suffered worse from the separation of races than Detroit.

Forced by federal housing policy and local practices into slums and nearly all-black neighborhoods, African-Americans lived apart from the city’s white population, which limited their ability to enroll in better schools in white neighborhoods or seize job opportunities across the city or suburbs.

A year after the fires of that summer, the commission, appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to examine the causes of riots across dozens of U.S. cities, recommended several policy changes to lessen segregation in low-income housing. They included:

- Making affordable housing available across metro regions

- Improving the quality of housing stock

- Making homeownership more attainable, and

- Creating policies that break down segregated neighborhoods and allow African Americans the freedom to live where they choose and closer to higher-paying jobs, what Michigan State University Prof. Joe T. Darden calls “the geography of opportunity.”

Nearly 50 years later, experts say not much has changed in metro Detroit, even as many black Detroiters have spread into communities across the region. The Detroit metro area remains by some measures the most segregated in the nation and housing advocates say many communities remain unfriendly to people of color.

While U.S. Census data show metro-Detroit made modest gains in easing segregation between 2000 and 2010, it hardly feels like progress to those who monitor the housing industry.

“It hasn’t changed at all,” said Margaret Brown, executive director of the Fair Housing Center of Metropolitan Detroit, a nonprofit that investigates discrimination claims in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counities. She said her group still receives hundreds of complaints annually from would-be tenants and homebuyers and that the number one complaint remains racial discrimination.

Segregated communities, as Bridge Magazine’s reporting has shown, extract a disproportionate cost on people of color by limiting access to employment, to transportation that will get them to jobs, to clean water and air and to education, while making it far more difficult for African-American families to accumulate wealth.

Together but apart

Detroit is now 82 percent African-American, roughly double its presence in 1967. And blacks can now be found in almost every city and town in the larger region of Oakland, Wayne and Macomb counties. And yet, even as African Americans continue to follow whites to live and work in the suburbs, metro Detroit remains largely segregated, with whites in largely white neighborhoods and blacks living among blacks, even within the same town.

In fact, the average African-American resident in the region lives in a census tract that is at least 81 percent black, according to Brown University researchers. While most whites live in areas where they are far and away the majority.

Even in cities that appear integrated, like Ecorse, where African Americans comprise 42 percent of the population, the numbers deceive: West of the city’s railroad tracks, blacks are 97 percent of the population. East of the tracks, they comprise just 11 percent.

It’s not just where they live, but how: Recent housing statistics show that blacks still are far more likely than whites to live in rental apartments and homes of poorer quality and that consume a higher portion of their income.

And those African-American residents living outside Detroit are far less likely to live in middle-to-upper income suburbs like Sterling Heights, Wyandotte or Birmingham, and more likely in older, inner-ring cities in flux, like Eastpointe, Warren and Oak Park, where property values are stagnant or falling.

“We really have made very little progress,” said Peter Hammer, a Wayne State law professor and director of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights, which promotes the rights of vulnerable populations in urban areas.

Some may look at the paths taken, from African-Americans choosing Southfield, now majority black, or whites moving to Rochester and Romeo, and see them as personal choices. They may wonder if the segregation that now exists, years after the official abolition of mortgage redlining – when blacks were unable to get loans because of their race -- is the result of preference, not discrimination.

But those who closely document Detroit-area housing patterns see less benign forces at work, even today.

“The whole notion of freedom of choice can’t begin to explain the depths of the segregation in the metropolitan Detroit area,” said Thomas Sugrue, an historian at New York University and author of the seminal “The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit,” a book that, among other things, examined Detroit’s troubled racial history to explain segregation in the United States.

A native of Detroit, Sugrue shows in “Origins” that, long before 1967, blacks faced enormous housing discrimination, some of it legalized in real estate documents – such as restrictive covenants that banned homeowners from selling their homes to blacks -- in federal lending, or in local housing practices. It led to the near universal separation of the races.

“There has never been a free market for housing in (metro) Detroit and in most American cities for African-Americans,” Sugrue told Bridge.

Nearly 50 years later, segregation patterns may be fraying, but remain the worst of all metro regions in the country.

When a road become a moat

Historically, 8 Mile Road, the northern border of Detroit, was a racial demarcation line; blacks typically did not live north of it. For the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s, moving across that line – and into the western and southern suburbs – defined the white flight that helped depopulate the city.

Yet in recent decades tens of thousands of blacks moved north of 8 Mile. Yet many whites also moved – even farther north. What was the pattern in Detroit through the 1950s and 1960s, when the “black line” inched farther east and west within the city, is now happening well beyond Detroit.

“So the old 8 Mile becomes 12 Mile and you have this notion of ripples of white flight which you still see today,” Wayne State’s Hammer said.

Consider the city of Warren, a traditionally white enclave in Macomb County, just northeast of Detroit, epicenter of the socially conservative, blue-collar demographic of so-called “Reagan Democrats.” In 1970, Warren had just 132 blacks among it 179,000 residents. Today, there are more than 20,000 African-Americans living in the city, a full 15 percent of population.

An integration success story? On the surface, perhaps.

But most blacks in Warren now live in older neighborhoods, in smaller homes that they’re renting in the southern tier of the community closest to Detroit. In neighborhoods just a few miles north, Warren still has nearly all-white census tracts where blacks account for less than 2 percent of the population.

“So the pattern,” Hammer said, “is reproducing itself and we’re showing cyclical patterns and we’re not making any meaningful progress and actually dealing with the core problem.”

At the time of the 1967 riots, nearly 90 percent of the region’s blacks lived in the city of Detroit (actually, in one half of Detroit; many city neighborhoods remained all-white). Another 10 percent lived in just six other communities: Pontiac, Highland Park, Inkster, Ecorse, River Rouge and Royal Oak Township, according to the 1970 Census.

Today, blacks and whites in metro Detroit are both far more likely to see each other in their communities on any given day, yet only 5 percent of whites and blacks live in a census tract that’s even close to the overall region’s black-white mix (25 percent black).

Metro Detroit is not alone in its segregation: the Cleveland, Chicago, Milwaukee and New York City metro areas all struggle with segregation nearly on the scale of Detroit. In fact, there are few examples nationwide where communities have successfully avoided racial polarization.

Shaker Heights, outside Cleveland, and Oak Park, just outside Chicago, are two suburban communities that consciously promote racial integration through housing policy. But, as Sugrue points out, “These places are few and far between,” and not close in scale to cities like Detroit.

Still, there are hints of progress to go along with concrete examples of continuing problems.

A survey on racial attitudes this past summer, sponsored by the Detroit Journalism Cooperative of which Bridge is a member, shows that blacks and whites in the region view the impact that race may have on housing patterns a bit differently.

While 12 percent of whites said the racial composition of a neighborhood played a role in their decision to live there, nearly 20 percent of blacks said it did. Sixty-percent of both groups said they lived in an area where most people looked like them.

However, one-quarter of whites said they’d be unwilling to live where they’d be in the minority, compared to 16 percent of blacks.

Those attitudes are reflected in the current demography of the region: Only a couple of metro Detroit communities – New Haven in northern Macomb County, Sumpter Township in southwestern Wayne County, West Bloomfield in Oakland County – have seen their black populations remain sizeable and stable over recent years.

Even then, the diversity in the community is not always reflected in the local schools. A Bridge investigation this year found that parents across Michigan often use the state’s generous “Schools of Choice” program to move their children to less diverse schools.

For much of the 20th Century, blacks living in Detroit were blocked from some public housing, could not get homes loans and were not welcome in many white-dominated neighborhoods, problems well chronicled by advocates who fought to overcome the obstacles.

“What white Americans have never fully understood,” the Kerner Commission wrote, “but what the Negro can never forget, is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it and white society condones it.”

Even after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, which sought to eliminate housing discrimination, hurdles remained. Restrictive covenants and U.S.-backed redlining were gone, but some real estate agents still illegally steered black and white buyers to less diverse neighborhoods, a practice that housing advocates say continues today.

Every week black and white “testers” – who play the role of people looking for a home or apartment then report back to how they are treated – fan out across Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties. The Fair Housing Center’s Brown said she’d run out of money before the center would run out of trouble spots to investigate.

What the testers find is disheartening, she said: landlords telling whites the rent is one price but blacks a higher one; blacks being told an apartment is no longer available when it is, or that a rental needs a co-signer while not asking the same of whites – all, if proven, blatant violations of housing law.

“When we send testers out, they (black testers) are told things that aren’t true,” Brown said.

Since 1977, the center said it has won over $11 million in settlements for tenants and homeowners. It recently challenged Oakland County over its use of federal housing money, alleging it was not using it to help low-income families as required and perpetuating segregation. The complaint is still under review by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Brown said.

Segregation has often narrowed the paths of blacks leaving Detroit to neighborhoods where they could afford homes and felt they were considered welcome. Studies have shown African Americans are usually willing to move into racially mixed areas but less willing to become “pioneers” in all-white areas.

“The patterns of African-American movement into the suburbs outside of Detroit aren’t random,” Sugrue said.

Victimized again

Ironically, after decades of seeking equal access to home loans, blacks were given wider access to loans in the 2000s. But at a fearsome cost: The predatory lending that flooded into Detroit that decade – an estimated three-quarters of all loans from 2004 to 2006 carried higher interest rates -- saddled tens of thousands of residents with high-interest loans they could not afford.

Then, when owners couldn’t pay, banks foreclosed on 100,000 properties in Detroit, more than a quarter of all housing units in the city. That depressed the city’s housing market further and contributed mightily to the problems that led the city to file for bankruptcy.

“You could say the next wave of housing market discrimination, one that provided access to loans and mortgages to African Americans, was a different form of exploitation,” Sugrue said. “It was predatory.”

In many cases, that led to foreclosures, first from lenders and later from the government. When owners could not pay their tax bills – Detroit has some of the highest property tax rates in the state -- many lost their homes to auctions held by the Wayne County Treasurer. The ACLU of Michigan and the NAACP this year sued the treasurer’s office, claiming assessments were not lowered to match lowering property values and that foreclosure was carried out in a discriminatory manner.

Beyond that, Hammer said: “The other irony is housing is made available to African-Americans and other minorities oftentimes in markets that are in decline.”

When opportunity finally struck, many bought homes in Detroit, their tiny piece of the American dream. But now, a city that now owns tens of thousands of vacant properties and is hoping to demolish many of them, many of those home sales are not looking like a sound investment, exacerbating the region’s black-white wealth gap.

“What’s the value of that home now?” Hammer said.

Not the first time

In the wake of the Kerner Commission findings, lawmakers made changes to alleviate housing discrimination, with mixed results.

In the 1970s, after the Federal Housing Agency began backing loans for the poor, speculators combined with shady appraisers to inflate home prices. They helped thousands of poor families get loans to buy their first homes in Detroit.

But the deals were often for unsound homes that never matched the value of their loans, with bribes to government officials greasing the wheels for costly mortgages. The new owners, most long-time renters, paid as little as $200 in down payments before moving in. When problems arose in the homes – some were slated for demolition before unscrupulous real estate agents made minor repairs and sold them – the owners just walked away.

The resulting scandal left the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development owning more than 25,000 derelict properties in Detroit, a foreshadowing of the subprime crisis 40 years later.

Around the same time, wealthier, whiter communities across Metro Detroit, including Warren, Livonia and Birmingham -- which combined, in 1970, counted 191 blacks among their 315,000 residents -- found themselves under scrutiny for not using federal money, as required, on low-income housing, or blocking the development of such units.

Ultimately, Birmingham, one of the wealthiest communities in the state, allowed the construction of low-income apartments and Warren is now home to the fourth largest black population in the region. Livonia, where fewer than 1 percent of residents were black as recently as 1990, now has more than 2,900 African Americans, roughly 3 percent of total population.

So there has been progress. Will it continue? Will the region find more racial balance in where people live and work, and create broader opportunities for success?

Margaret Brown, the housing official, was just a young girl in 1967, growing up in Northwest Detroit when the city erupted in violence that summer.

She remembers the civil rights struggles, the calls for fair housing and opportunity so that someday blacks could reach the “promised land” that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., prophesized the night before his death.

But today, the path to secure a good, safe place to live is still blocked by prejudice, still hampered by inequality, Brown said. Complaints of discrimination remain “constant, persistent, not changing.

"I would have thought the things we were fighting...would have disappeared by now,” she said. “And here we are in 2016, and where is that land we were talking about?"

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

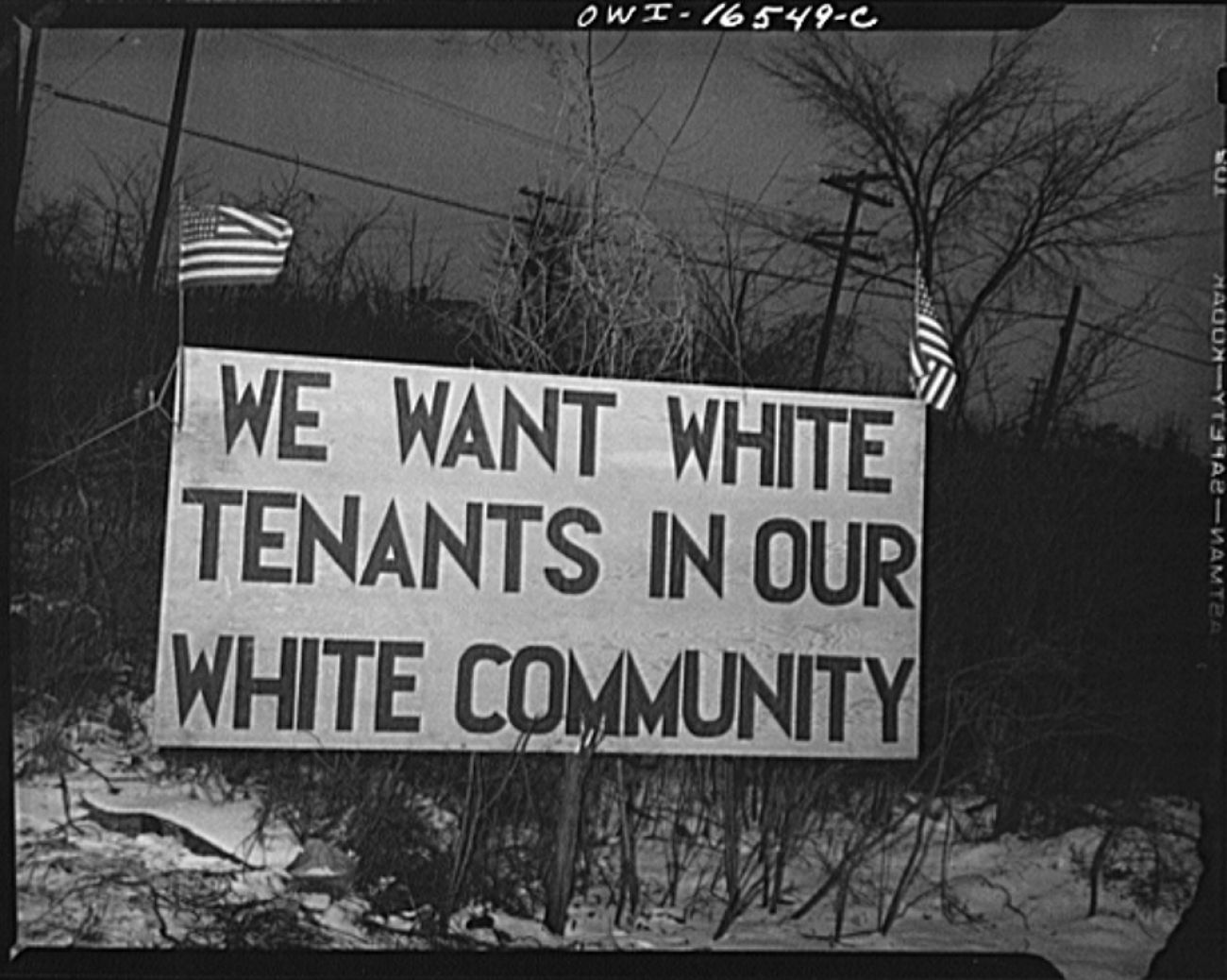

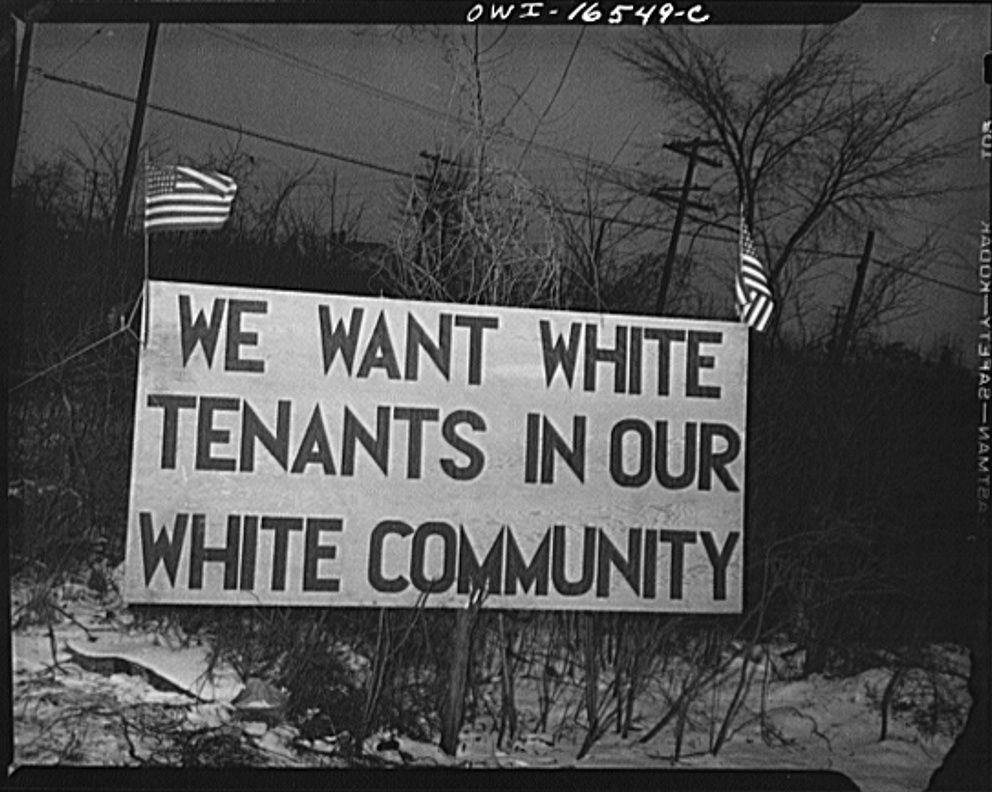

White residents of one northern Detroit neighborhood were not happy when a federal public housing development for blacks was announced in the early 1940s, during World War II.

White residents of one northern Detroit neighborhood were not happy when a federal public housing development for blacks was announced in the early 1940s, during World War II. Wayne State University law professor Peter Hammer notes that even as African-American families leave Detroit for the suburbs, blacks and whites continue to live largely separately, even within suburban communities.

Wayne State University law professor Peter Hammer notes that even as African-American families leave Detroit for the suburbs, blacks and whites continue to live largely separately, even within suburban communities. Celebrated New York University history professor and Detroit native Thomas Sugrue says housing discrimination has long contributed to racial inequities in Detroit.

Celebrated New York University history professor and Detroit native Thomas Sugrue says housing discrimination has long contributed to racial inequities in Detroit.