Some Michigan parents question whether schools should have health clinics

- Northville Public Schools is weighing whether to seek funding for two school-based health clinics

- Some parents say the district should focus on education rather than providing primary care services in schools

- The debate, in Northville and beyond, centers on whether students could gain some medical services without parental consent

NORTHVILLE— As schools try to respond to student mental health concerns, some families in this upscale community west of Detroit are pushing back on giving students access to a broader range of medical services.

Northville Public Schools is weighing a proposal to work with Michigan Medicine to open health clinics at a middle and high school. It carries financial benefits for the district, with the highly rated health system and the state paying for staff, including a nurse practitioner, licensed social worker, doctor, dietician and medical assistant. The district would have to cover building maintenance.

But at a public hearing Tuesday, some parents raised concerns over the range of services offered by the clinics. That could include, they noted, substance abuse and sexual health services that older teens do not necessarily need parental consent to receive under state law.

“The district would be facilitating the ability for a student to do things without parental knowledge,” Tammy Kane, a parent of a middle school student, said at the hearing. “Who will be responsible when it comes back to bite the district because the district chose to offer medical care rather than focus on their number one job, which is educating our children?”

Related:

- Michigan needs teachers. Melvindale high school students explore the career

- Controversial elsewhere, AP African American Studies widely popular in Michigan

- School choice here to stay in Michigan: See how it impacts your district

Similar debates are taking place in other Michigan districts, with parents raising concerns about parental rights and the breadth of health care offered to students. Last year, the Grosse Pointe Public School System and Oxford Community Schools stopped plans to open school-based clinics.

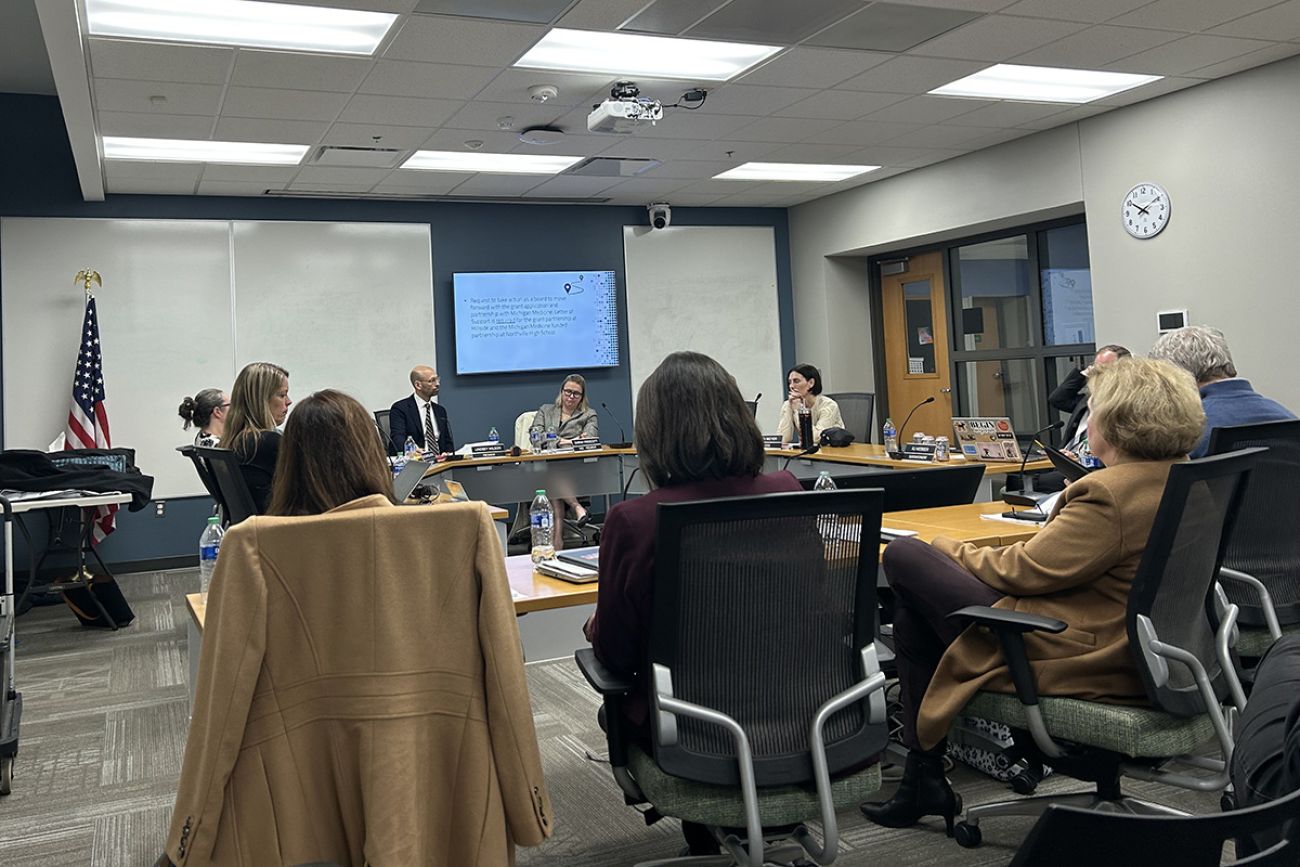

Roughly two dozen people spoke Tuesday at the Northville hearing, with about half supporting the clinics and half in opposition. After multiple hours of discussion, the school board chose to postpone a decision on whether to apply for state funding for the clinic projects.

What health care belongs in schools

Since the start of the COVID 19 pandemic, the state has poured over $700 million into bolstering school mental health resources, including for nurses, counselors, social workers and psychologists. In October, the Michigan Department of Education announced that more than 1,000 professionals had been added to schools over the past five years.

“Providing these services during the school day leads to early identification and intervention, better access to care, better academic outcomes, a more positive school climate and safety, better psychosocial outcomes, and better engagement with students, families, and educators,” said State Superintendent Michael Rice said at the time.

School-based health centers — which offer a combination of physical and mental health care — have been around for more than three decades, according to the School-Community Health Alliance of Michigan. The group’s website says there are 196 school-based or school-linked centers and programs in Michigan. Debra Brinson, executive director of the health alliance, said she has seen more questions around parental consent and how these clinics function in the last year and a half as parents take a more active role in learning about health services in schools.

School health clinics often serve communities where families are economically disadvantaged and families struggle to access medical care.

Indeed, some who spoke out against the Northville clinics said the district does not need a primary care clinic in the schools because they are readily available in the community.

“There are plenty (of) clinics in this area, all better-staffed than we’re going to have here,” Matthew Wilk, a former school board member and parent of two Northville high school students, told board members Tuesday night.

Jessica Jordan, a parent of two elementary students, told board members she supports the proposals.

“The evidence is very clear that children, particularly young women, are experiencing epidemic levels of depression and loneliness,” Jordan said.

“I think kids, particularly teenagers should have a safe space to talk about their issues with a medical professional in their school, versus turning to an alternative method that could be much more damaging like self-medication, violence or god forbid, self harm,” Jordan said.

Janet Tian, 17, a high school student, said she has struggled with mental health concerns and many of her peers are “burnt out, struggling and in need of care.”

Tian told the board that as students get older, it’s important they be given more space to make their own medical care decisions.

“I know that many adults, especially in this room, hold themselves accountable and responsible for all aspects of their child,” Tian said. “But as we grow, we also deserve a certain level of privacy and autonomy. We aren’t incompetent or irresponsible. We’re simply human. And while we can make dumb mistakes, we are also mature enough to decide to make the choice of seeking additional guidance and support.”

Opponents’ concerns ranged from being left out of their children’s medical decisions to whether it’s the proper role of a school district to be contracting with a medical provider.

Wilk, the former board member, told Bridge Michigan that if Northville is keen on finding solutions to mental health concerns, it should focus directly on hiring clinical psychologists and counselors, rather than approving the clinics.

“Michigan Medicine already has made their decision and their decision is on the far end of what parents find acceptable,” Wilk said.

More leeway to teens

Generally, a patient must be 18 to consent to medical services without the consent of the parent, said Denise Chrysler, senior advisor at the Mid-States Regional Office of the Network for Public Health Law, which advocates for strong public health policies.

But under Michigan law, older teens are given broader autonomy to seek some medical care on their own.

“(T)here's limited areas of care where the Legislature has determined that obtaining care is so important that they have carved out exceptions,” Chrysler said.

This includes care for substance abuse, sexually transmitted diseases and mental health concerns. Chrysler noted, however, that state law prohibits providers from distributing contraceptive drugs or devices on school property.

A Northville district document acknowledges instances where students can access confidential health services without parents’ knowledge or consent.

The minor consent form includes references to help with drug and substance abuse, sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy testing and birth control education and referrals without parent or guardian permission.

It also states that if the minor is 14 or older, they can get “limited outpatient mental health services without permission from my parent(s) or guardian.”

Northville Superintendent RJ Webber told Bridge that students can benefit from having both physical and mental health services available in one place, allowing the “whole child” to be treated.

Webber added that the opportunity to work with Michigan Medicine would allow Northville students to access more help than the district could afford to support with just its own funds.

What’s next

If the board moves forward with the clinics, the district would apply for a competitive grant administered by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to open the middle school clinic. Michigan Medicine would pay for the high school clinic.

The district would use existing state funds designed for mental health and school safety projects to build and maintain the clinics.

Last summer, the Legislature allocated $33 million to provide primary health care services to patients up to age 21. MDHHS spokesperson Lynn Sutfin said there are 168 school-based health centers funded by those funds.

Taryn Gal, executive director of Michigan Organization on Adolescent Sexual Health, said school health centers are “one of the best resources that young people have.”

She said the centers aim to work with parents but there may be instances where a student is sexually active and the student knows that if they told their parent, the student could be kicked out of the home or abused.

“I think young people have the right to know how to keep themselves healthy,” Gal said, “and it’s important that they be able to access treatment from somewhere that they know is safe.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!