Ready for college? In Michigan, likely not.

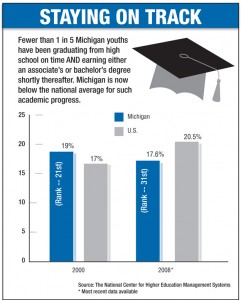

If you live in Michigan, your high-schooler is probably less prepared for college than the average American student. Your teen has only an average chance of graduating from high school, and a below-average chance of enrolling in college. And if your son or daughter makes it to campus, he or she is less likely to earn a degree than their out-of-state Facebook friends.

When it comes to preparing our kids for college, Michigan schools are losing the readiness race to dozens of states, including most of our neighbors.

An analysis of Michigan college readiness data by Bridge Magazine and Public Sector Consultants reveals a troubling track record. Almost half of the state’s public school districts score poorly in at least one measure of college preparation. The share of Michigan teens enrolling in college and earning degrees is barely budging. Tens of thousands are taking high school-level courses in college and dropping out even before becoming sophomores.

“If we don’t change,” warns Larry Good, chairman of the Corporation for a Skilled Workforce in Ann Arbor, “Michigan is going to be a poorer state.”

Little college = little dollars

Increasing college readiness is vital. Seven out of 10 jobs added to the Michigan economy between 2008 and 2018 will require some post-high school education, according to a Bridge analysis of job projections. By 2018, more than 37 percent of jobs are projected to require a bachelor’s degree or more, compared to 29 percent today.

“For families, college is the only reliable path to the middle class,” says Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future, a group advocating for advanced learning. “High college attainment rates raise everybody’s wages; if you’re a construction worker or a waiter, and you live in a high college attainment area, your wages are higher, too.”

It’s a mantra repeated by business leaders and politicians of all stripes. Former Gov. Jennifer Granholm championed the Cherry Commission report that laid out the economic necessity for increased college readiness. Gov. Rick Snyder chimed in last summer, saying, "Michigan's future, in large part will depend upon the readiness of our students to enter a career or college with the educational foundation needed to succeed and have a strong quality of life.”

To gauge how Michigan is faring, Bridge examined public school district-level data measuring ACT college readiness, Michigan Merit Exam proficiency, graduation rates and the percentage of high school graduates who require remedial (high school-level) courses when they enroll in college.

See how your district measures up in college readiness.

The results were sobering:

* Six out of seven Michigan school districts have fewer graduates deemed “college ready” than the national average, when measured by the ACT standard of being fully college ready.

* Only 39 percent were deemed proficient in all subject areas of the Michigan Merit Exam taken by juniors last spring.

* Of those who go on to Michigan public colleges, 35 percent take at least one remedial course, and 27 percent (more than 21,000 students in 2008-09) drop out before their sophomore year.

This is not just a crisis of Detroit, or urban centers. Districts ranging from poor urban to rich suburban to tiny rural have spotty track records for college readiness. Of the state’s 515 public school districts with complete data, 256 districts (49 percent) were in the bottom quarter of scores in at least one of Bridge’s college readiness measures.

Even top-rated districts serving affluent families have chinks in their academic armor. One in five Birmingham graduates take remedial courses in college to make up for high school deficiencies. In Grosse Pointe, just 38 percent of grads are considered “college ready” by their scores on the ACT. In Ann Arbor, one in six don’t graduate from high school.

“Neither Michigan nor the country has done well” preparing students for college, said William Schmidt, a professor of education at Michigan State University. “It’s our children’s futures that are being held hostage. It’s economically stupid and it’s morally questionable.”

“I’m troubled because the system doesn’t make it easy to (attain) college readiness,” says State School Superintendent Mike Flanagan. The “system” Flanagan blames goes far beyond high school classrooms and local school board meetings. He theorizes the state’s college readiness problem starts while kids are still watching “Sesame Street.”

“We don’t fund early childhood (education),” Flanagan said. “We spend about a billion dollars a year on grades K through 12, and we spend hardly anything when the brain is being developed. Early childhood really will transfer to college readiness.”

Flanagan has seen data that links third-grade reading proficiency with college readiness. “If kids aren’t reading on grade level at third grade, the odds are they aren’t going to be college ready,” he said. “To me, the only way they’re going to get third grade reading proficiency is to have a robust early childhood program for every child.”

Schmidt blames lenient cut-off scores -- the scores that split proficiency from non-proficiency -- on the state’s MEAP tests for poor readiness. In the past, those cut-off scores allowed districts to earn deceptively high proficiency rates. “Michigan’s curriculum standards were of high quality,” says Schmidt, a university distinguished professor of statistics who was instrumental in developing the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). “But they set a cut point that was so low, it effectively mitigated the high standards.”

And those cut scores were set for political reasons, claims Schmidt, to make it appear Michigan schools were making more progress than they actually were. (The cut scores were raised significantly in 2011.)

Flanagan also thinks teacher-training programs at Michigan colleges share responsibility. “If you give me better-prepared teachers, I’ll give you better-prepared (college) freshmen,” he said.

The state’s new curriculum standards, put into place five years ago, eventually will increase college readiness by adding “clarity” to what should be taught at each grade level, Flanagan said. “You can’t teach the solar system every year because you like it. Districts now know the content expectations for each grade.”

It’ll be another eight years, though, for the first class to have gone through the new curriculum from kindergarten to graduation. Schmidt, who helped benchmark the new curriculum, said he hopes the state has the “political will” to maintain college readiness efforts that won’t show immediate results.

“It’s a cycle -- from early childhood education to core curriculum to better-prepared teachers -- and it takes time,” Flanagan said. “And some states kicked into gear earlier than us.

“Inching forward is disappointing in some ways,” Flanagan says, “but it’s on its way.”

Senior Writer Ron French joined Bridge in 2011 after having won more than 40 national and state journalism awards since he joined the Detroit News in 1995. French has a long track record of uncovering emerging issues and changing the public policy debate through his work. In 2006, he foretold the coming crisis in the auto industry in a special report detailing how worker health-care costs threatened to bankrupt General Motors.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!