Public wants to help teachers improve

The best way to improve schools is to improve the skills of the person standing in the front of Michigan classrooms.

Teaching teachers to do their jobs better is the education reform Michigan residents believe will most improve our schools, according to the largest effort ever to collect and analyze public opinion on K-12 education in Michigan.

That approach is more popular than better-known reforms such as expanding school choice, online learning and changing the school calendar among more than 7,500 participants cited in The Center for Michigan’s* report, “The Public’s Agenda for Public Education.”

That report, representing the views of participants in more than 250 community meetings across the state and two scientific polls, revealed a public desire to improve teacher quality through better schooling before teachers earn a degree, more professional development once they’re in the classroom and more rigorous accountability to weed out teachers not cutting the mustard.

The road to high-quality teaching

While the impact of some education reforms remains murky, high-quality teaching definitely makes a difference, says Melissa Usiak, principal of Sycamore Elementary in Holt in mid-Michigan. She cites a 2003 study by Robert Marzano, a Colorado-based education author and reseacher, linking teacher effectiveness to student achievement.

In the study, a student at the 50th percentile entering a classroom with a highly effective teacher could end the school year scoring at the 96th percentile; in an ineffective teacher’s classroom, the child could leave scoring at the 37th percentile.

“Those numbers are devastating,” Usiak said.

“A lot of people don’t understand how complex teaching is,” said Amber Arellano, executive director of Education Trust-Midwest, a reform group. “Great teachers are really works of art. They’re very rare.

“Other states are showing great gains … by investing in teachers,” Arellano said. “It’s not about pouring money into it -- it’s about building more supports and systems, and building capacities of local schools to do that.”

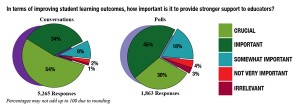

Topping the public’s reform agenda was a statewide effort to offer stronger support for educators. Among community conversation participants, 88 percent considered stronger support for educators to be “crucial” or “important.”

“More support is crucial – teachers are now being asked to be nurses, housemaids and more on top of their teaching duties,” said a participant in a community conversation in Grand Rapids.

Continuing in-school training, teacher mentors and professional learning communities (in which teachers work together to develop teaching strategies) all make a difference. Education Trust-Midwest recommends Michigan encourage teachers to earn National Board Certification – what amounts to a voluntary, national master teacher credential. Teachers earn certification through an exhaustive assessment process designed to recognize highly-effective teaching practices.

Students of National Board Certified teachers tend to do better academically.

“I started my career as a teacher outside Flint,” Arellano recalled. “I probably got about 20 minutes of feedback in my first four months. The void in support and training is incredible.”

“I remember the early 2000s, there were a lot of teacher mentors out there to work with new teachers, sharing the experience they’d learned over decades,” said Doug Pratt, director of public affairs for the Michigan Education Association, the state’s largest educators union. “They were incredibly valuable. Those positions are almost completely gone because of budget cuts.”

How best to teach teachers?

One way to improve teacher quality is to improve teacher education at Michigan colleges. Four out of five participants in community conversations and polls want incoming teachers to be better prepared when they enter the classroom.

Michigan residents also want teachers to be plucked from the most gifted, passionate and motivated students, something that doesn’t happen in all education departments today. Support for that idea was highest among African Americans, Hispanics, parents and people with low incomes. Even educators showed overwhelming support for raising the bar on teacher training.

“When I was in a teacher preparation program, I was disappointed with the expectations for us and the work we had to do,” said a community conversation participant in Flint. “I was embarrassed. It could have been my individual experience, but you would never see in a science class 90 percent of your students with a 4.0 grade point average.”

Gov. Rick Snyder has said he favors reforming how Michigan recruits and prepares educators, including raising the score necessary to pass teaching certification exams, which teachers must pass to get a job in Michigan.

Suzanne Wilson, chairwoman of the nationally ranked College of Education at Michigan State University, said there is “wild variability” in the quality of teacher training programs. “It’s perfectly legitimate for the public to be concerned about how we certify teachers. It’s a civic responsibility to produce high-quality teachers.”

State policy-makers need to “understand more about what it takes to be a good teacher prep program, and hold all (schools) accountable to meet those standards,” Wilson added.

One option Wilson advocates: responsible admission standards to get accepted into a teaching program.

“Some, it’s hard to get into,” she said. “Some, it’s easier.”

“Finland, along with some other European countries, recruits (teachers) from the top third of the class and we don’t do that,” said a community conversation participant in Hamtramck. “Education is looked at as a fallback career here in the U.S. An education degree should be more difficult to obtain.”

Tying classroom results to career tracks

Teachers should get a high-quality education in college and support in the classroom, but in the end they should be held accountable for the success or failure of their students. That’s the clear signal given by Michigan residents, two-thirds of whom support holding educators more accountable. Among the more than 7,500 voices reflected in the report, the measure received the most support from African Americans and employers. Educators showed the least support, with 61 percent of educators in community conversations and 46 percent in polls viewing increased accountability as crucial or important.

“There is no profession where people are not held accountable,” said a community conversation participant in Haslett. “If you don’t hit the objectives then a closer look can be taken to see what is going on. Without accountability then the oldest teacher wins and the new good teachers get pigeonholed.”

Michigan teacher evaluations traditionally rated almost all teachers as good or great. Those evaluation standards are slowly becoming more stringent, with student achievement becoming a larger factor.

Some participants worried that reliance on student achievement to grade teachers would harm good teachers toiling in high-poverty schools, where many students struggle academically.

“A lot of areas that teachers could be measured on, they have no control over, like poverty in students,” remarked a community conversation participant in Milford. “This results in more pressure on teachers, more likelihood of cheating from teachers wanting to hit their numbers.”

The Michigan Council on Educator Effectiveness is developing a teacher evaluation model that will be presented to the state later this year. That model is likely to take into account numerous factors, including the poverty level of children.

Bridge Magazine recently developed a school scorecard that analyzed standardized test scores adjusted for student income. That report looked at the performance of school districts and charter schools, not individual teachers.

Increased accountability alone won’t fix Michigan schools, argues John Austin, president of the Michigan State Board of Education.

“I’m for good evaluation, but you also need funding for teacher development,” Austin said. “Our teachers are getting less resources to get better while being asked to get better. States that are successful have accountability, but they also have master teachers and teacher development” on a scale Michigan doesn’t currently fund.

*The Center for Michigan is the parent organization of Bridge Magazine.

Senior Writer Ron French joined Bridge in 2011 after having won more than 40 national and state journalism awards since he joined the Detroit News in 1995. French has a long track record of uncovering emerging issues and changing the public policy debate through his work. In 2006, he foretold the coming crisis in the auto industry in a special report detailing how worker health-care costs threatened to bankrupt General Motors.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!