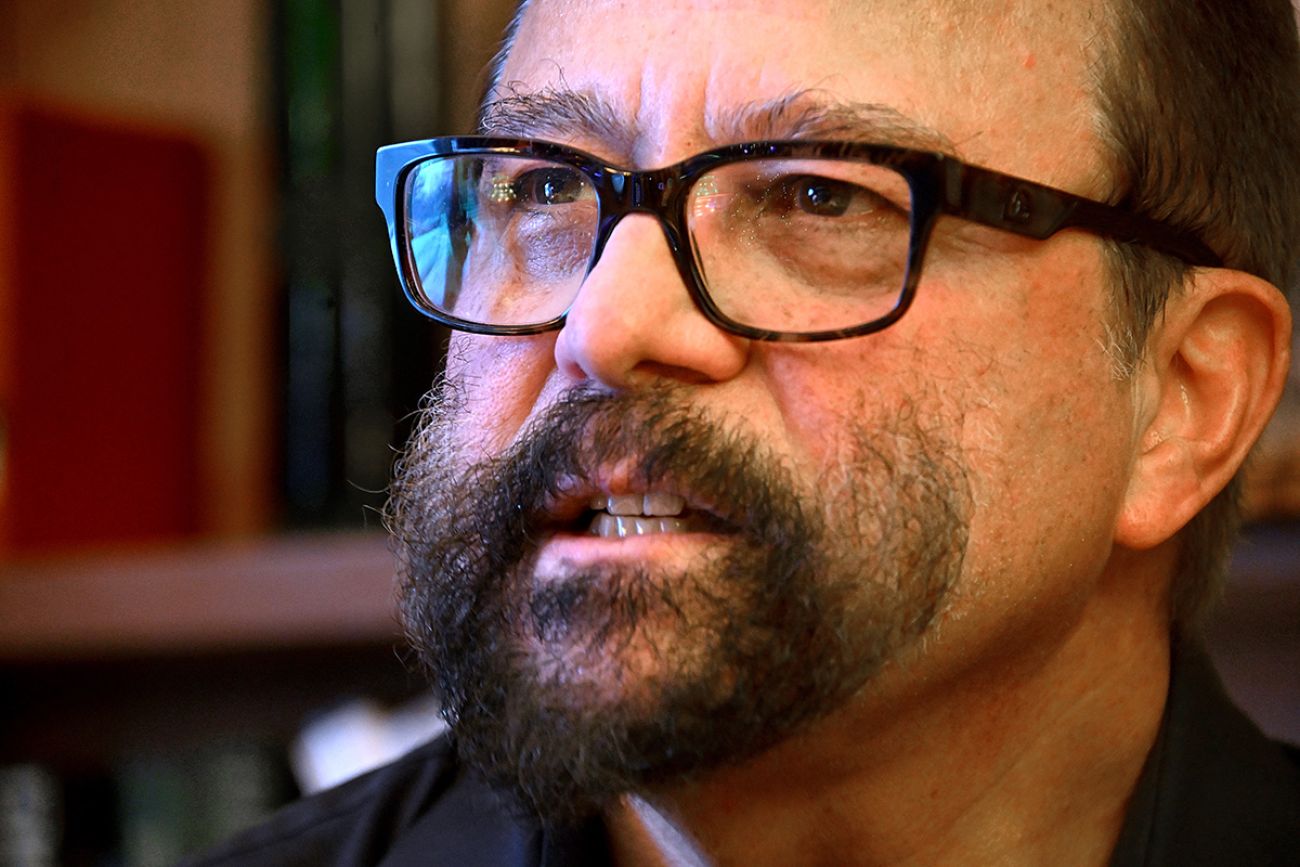

MSU professor saw students die. A year later, he fights for ‘a good life’

- Professor Marco Díaz-Muñoz watched a gunman enter his classroom on Feb. 13, 2023, shooting several students and killing three

- In the months afterward, he dedicated himself to helping his students emotionally recover

- His nightmares have subsided, but the professor still often feels ‘like I’m waiting for the next shoe to drop’

EAST LANSING — For nearly a year, Michigan State University Professor Marco Díaz-Muñoz managed to avoid Berkey Hall.

It was in his classroom,114 Berkey, that a gunman entered without warning last February, firing indiscriminately at students, killing two and critically injuring five others.

As the months passed, Díaz-Muñoz had begun to recover from the trauma of that evening. That meant returning to his routines, including teaching the same night class on Cuban cultural identity, though in a different building.

But Berkey, a brick building opened in 1945, continued to haunt him.

Related:

- Michigan State professor details terror of mass shooting in Room 114

- Lawyers: MSU to pay $15M to families of 3 students killed in campus attack

- What Michigan State asked, and didn’t ask, in its review of campus shooting

- Michigan State University expands ability to issue emergency alerts

- MSU's long path ahead: What other universities have done after mass shootings

He’d been deliberate to avoid even glancing at the structure until a recent night, when a construction detour forced him to drive toward the darkened building.

“I started feeling nervous,” said Díaz-Muñoz, 65, a professor of language and humanities.

Memories of flashing ambulance lights came flooding back, and he couldn’t bear to look directly at Berkey Hall. But he pressed on — another step toward reclaiming his place on a campus forever changed.

On a recent afternoon, Díaz-Muñoz reflected on the tragedy’s lingering impact. Feb. 13 will mark a year since MSU students Arielle Anderson and Alexandria Verner were killed in his class, as he and other students tended to the wounded while frantically trying to block doorways in case the gunman returned. A third student, Brian Fraser, was killed minutes later at the MSU Union.

“I didn’t break down,” Díaz-Muñoz said of his drive past Berkey Hall. “But it felt uncomfortable. Things like that are just part of my life now.”

Staying on for the students

Within minutes after the shooting, the professor said he had already begun to dissociate from the event. Survivors were escorted to the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, where they spoke to law enforcement officers and mental health counselors.

Díaz-Muñoz said he found himself describing the night’s events as if they had happened to someone else.

For the next two days, being awake was torture. He struggled to reconcile his own physical safety with the young lives lost. So he took pills to stay asleep.

Then he awoke on the third day, and thought of his surviving students. The horror he’d felt transformed into an overwhelming concern for their wellbeing.

The university offered to excuse him from teaching the rest of the semester, but the professor refused.

“Those kids have to continue that class,” he thought. Asking them to finish the semester with a new instructor, who may not understand what they’d been through, felt like “leaving them out in the cold.”

Instead, he decided he would pour his energy into modeling recovery for his students. He wanted them to know, he said during an interview this week in his Lansing home, “that they still deserve a good life, and I deserve the same.”

By the time MSU students resumed classes a week or so later, Díaz-Muñoz’ Cuban cultural identity class had shrunk from 45 students to about 35. In addition to the dead and injured, several students had dropped.

Counselors were on-hand that day. Díaz-Muñoz said one student bolted into the hallway, overcome with emotion. He could hear her sobbing as she repeatedly told a counselor: “You weren’t there. You weren’t there.”

So Díaz-Muñoz exited the classroom, looked her in the eye and said, “I was there.”

Gradually, the class resumed their studies. Twenty-two students completed the course, working from a pared-down version of the original syllabus.

The professor felt proud of his students. But by the end of the semester, he again found himself struggling. Supporting his students had been something solid, grounding. Like holding onto a sturdy branch in a flood.

“But the branch to which I’m holding is going to be gone,” he realized.

‘50,000 people traumatized that day’

When spring semester ended, Díaz-Muñoz collapsed in a state of exhaustion. He said he began having regular nightmares, yet dreaded waking up to each morning. When awake, he struggled to access memories about the shooting.

“It’s there, like something in the corner of my eye that I’m not focused on,” he said. “Or something in a drawer that I don’t pull open.”

For those removed from the carnage, mass shootings are often an abstract threat, one easily forgotten when the news cycle moves on.

But in the U.S., the only country where these tragedies regularly happen, the ranks are growing of those who’ve come face to face with a mass shooter, feared for their lives during a campus-wide lockdown, or experienced a loved one’s death or trauma.

For them, the events can have a lasting effect.

“There were 50,000 people traumatized that day,” Díaz-Muñoz said, referencing the students, faculty and staffers across the sprawling MSU campus. “If they didn’t see what I saw, they were frightened that it was going to happen to them.”

Indeed, thousands of students and staffers were on lockdown for hours that night, as police searched for the gunman. Later that night, he killed himself when confronted by officers.

To illustrate the ripple effects of the trauma, Díaz-Muñoz cited his cats and dog. House pets are famously in-tune with their owners’ emotions. For weeks after the shooting, he said his dog was nervous, barking and aggressive. The cats still haven’t broken the habit of urinating on the carpet.

“The stress of the last year really did a number on them,” Díaz-Muñoz said.

A fall sabbatical in Europe allowed the professor to regain a sense of control, and he felt joy for the first time while conducting research. Since returning to campus this January, weekly therapy has helped him continue to process what happened, avoiding the temptation to “suppress it all.”

Back to class

Díaz-Muñoz still teaches the same humanities class on Monday and Wednesday nights, though it has been moved to a new location about an eight-minute walk south. His new students are aware of what he went through, but he prefers to keep classroom discussions on the coursework.

Outside of class, it’s another matter.

Díaz-Muñoz grew up in Costa Rica, a country with no military and strict gun laws. He has always been baffled by America’s gun culture, he said, and the MSU shooting reinforced his belief that the country’s gun policies are too lax.

In the past year, he has spent time advocating for stronger laws.

In March, he testified in support of gun control legislation sponsored by Democrats in the Michigan Legislature. Several bills passed, including universal background checks, a requirement for gun owners to securely store their firearms and a “red flag” law that allows judges to confiscate weapons of those deemed a danger to themselves or others,

But Díaz-Muñoz said he sees deeper cultural and economic issues at play in the nation’s mass shooting epidemic, and he fears they can’t be addressed by changing gun laws or locking down more public spaces.

Namely, a “lack of humanity” arising from worsening income inequality, a weakened social safety net, and a culture of fear and resentment that is stoked by politicians and reinforced on internet forums.

Police, neighbors and family described the MSU shooter, 43-year-old Anthony McRae of Lansing, as a loner with untreated mental health issues. He had worked low-wage jobs while his father collected scrap metal to make ends meet. After the shooting, police found a note on McRae’s body claiming that people “hate me”; and he described himself as an “outcast.”

“Now imagine someone like this … finds themselves in front of a computer monitor resenting their circumstances, and not having the right meds or the right counseling or the right psychiatric help,” Díaz-Muñoz said.

Despite his frustrations with what he sees as root causes of America’s mass shooting problem, Díaz-Muñoz said the shooting hasn’t tarnished his high opinion of MSU, and the state of Michigan.

In some ways, it has reinforced it.

Strangers who heard about the shooting sent emails, letters, and artwork expressing their support. A colleague at the University of Michigan sent more than 100 handmade paper cranes — a Japanese symbol of hope — for him to pass out to his students. For months, colleagues delivered meals to his house and offered to escort him to his night classes.

Lately, Díaz-Muñoz has begun turning down those offers. He is striving for normalcy, he said, though the trauma of that night still surfaces occasionally. He often feels restless, and has developed an obsession with maintaining a to-do list.

“It’s like I’m waiting for the next shoe to drop,” he said.

He is grateful that a key card is now required to access campus buildings after 6 p.m. Unlike his former classroom in Berkey Hall, the doors on his new classroom can lock from the inside. But he resists the urge to bolt them shut, saying he refuses to “let fear invade my life.”

He said he now sees students in a new light. Before, their youth made them seem so full of life that mortality was a distant concept.

“I just thought of them as people that have 50 years plus ahead of them,” he said.

Those lives now seem more vulnerable, and precious.

“They don’t know they’re vulnerable,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “But I see them. And I cannot take them for granted.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!