In Michigan, voters sour on school bonds. Once an easy sell, half now fail

- Statewide, local elections to increase funding for public safety and roads overwhelmingly pass

- That used to be the case as well for school districts, but in recent years, nearly half now fail

- It’s more than the economy, experts say: Distrust, confusion and timing of votes can make a difference

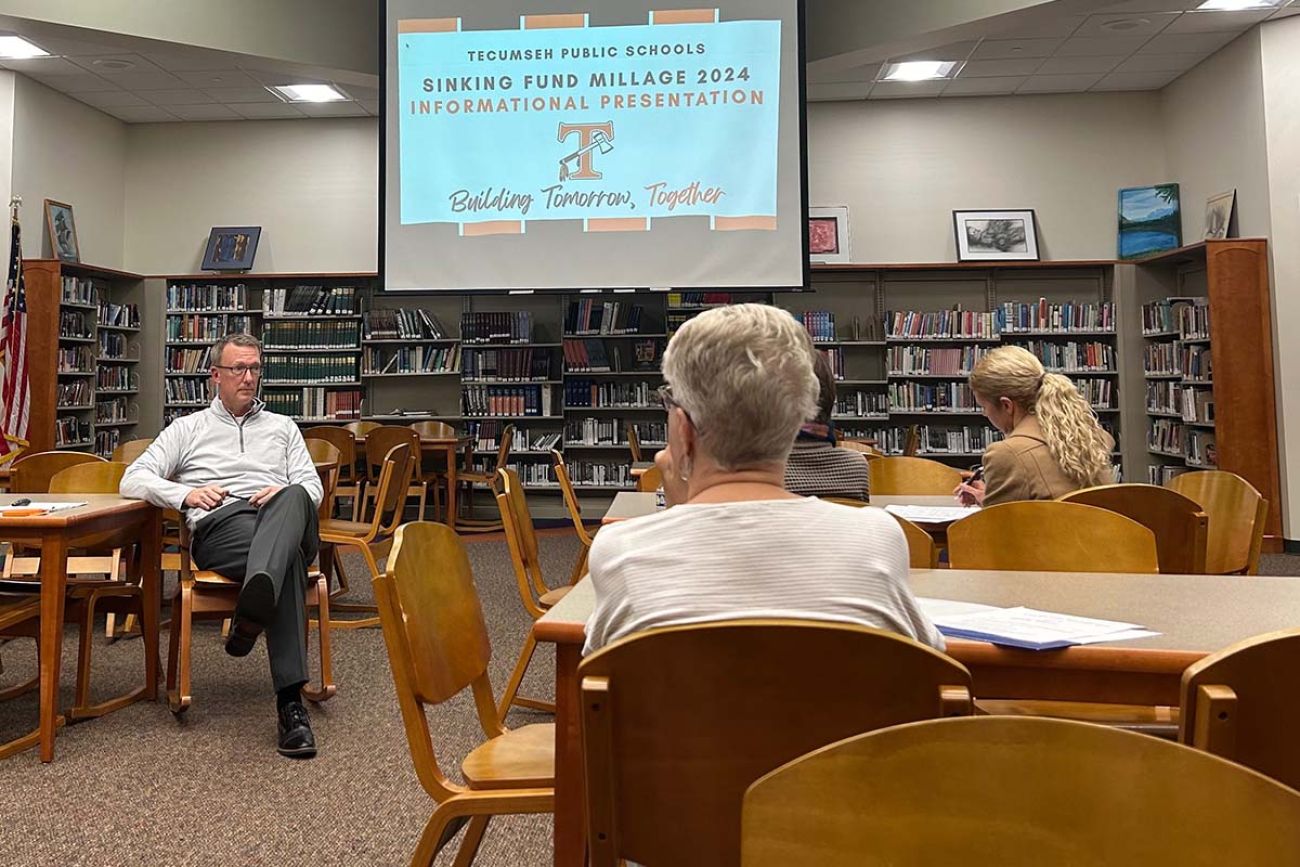

TECUMSEH — In the library of Tecumseh High School, Superintendent Matt Hilton makes a pitch to voters: school buildings need money for repairs, and the district is not here to ask voters to pay for extravagences.

The district is seeking a tax increase expected to generate $7.5 million over five years to pay for building repairs and upgrades. That’s a fraction of the combined $88.5 million in bond proposals for school infrastructure local voters rejected two years ago.

About this collaboration

Bridge Michigan and Gongwer News Service-Michigan collaborated for this project. Bridge analyzed data gathered by Gongwer, a subscription news service that covers the Michigan government. Click here for more about Gongwer or for a free trial.

Tecumseh is one of more than 50 districts asking voters in November to approve sinking funds or bond measures. For bonds alone, schools statewide want nearly $1 billion.

If recent history is a guide, many requests will fail. So far this year, nearly half of the 44 bond requests were rejected statewide, down from a passage rate of just under 75% of the 170 bond issues put before voters statewide from 2018-2020.

It’s an abrupt turn that other tax increase requests — for police, roads, libraries, parks and senior citizens — have not endured. Since 2018, those millage issues rarely lose, with 94% of over 850 requests passing just this year, according to a joint investigation by Bridge Michigan and Gongwer News Service.

Voters are defeating school bonds at higher rates statewide, but they’re higher in Republican-leaning areas like Tecumseh, according to the Bridge and Gongwer analysis.

Experts say easy answers are elusive, but point to the economy, complicated nature of school finance and shifting attitudes about public education since the pandemic.

Whatever the case, millages face uphill odds in Tecumseh, so its superintendent, Hilton, is making the rounds with voters, business groups and civic organizations.

Related:

- Five things to know about Michigan school bond proposals this election

- Dems OK $125M for Michigan school safety, mental health. GOP wanted more

- Michigan's mental health crisis extends beyond students: Teachers struggle too

- In Michigan, 1 in 3 students miss 18+ days of school a year, data shows

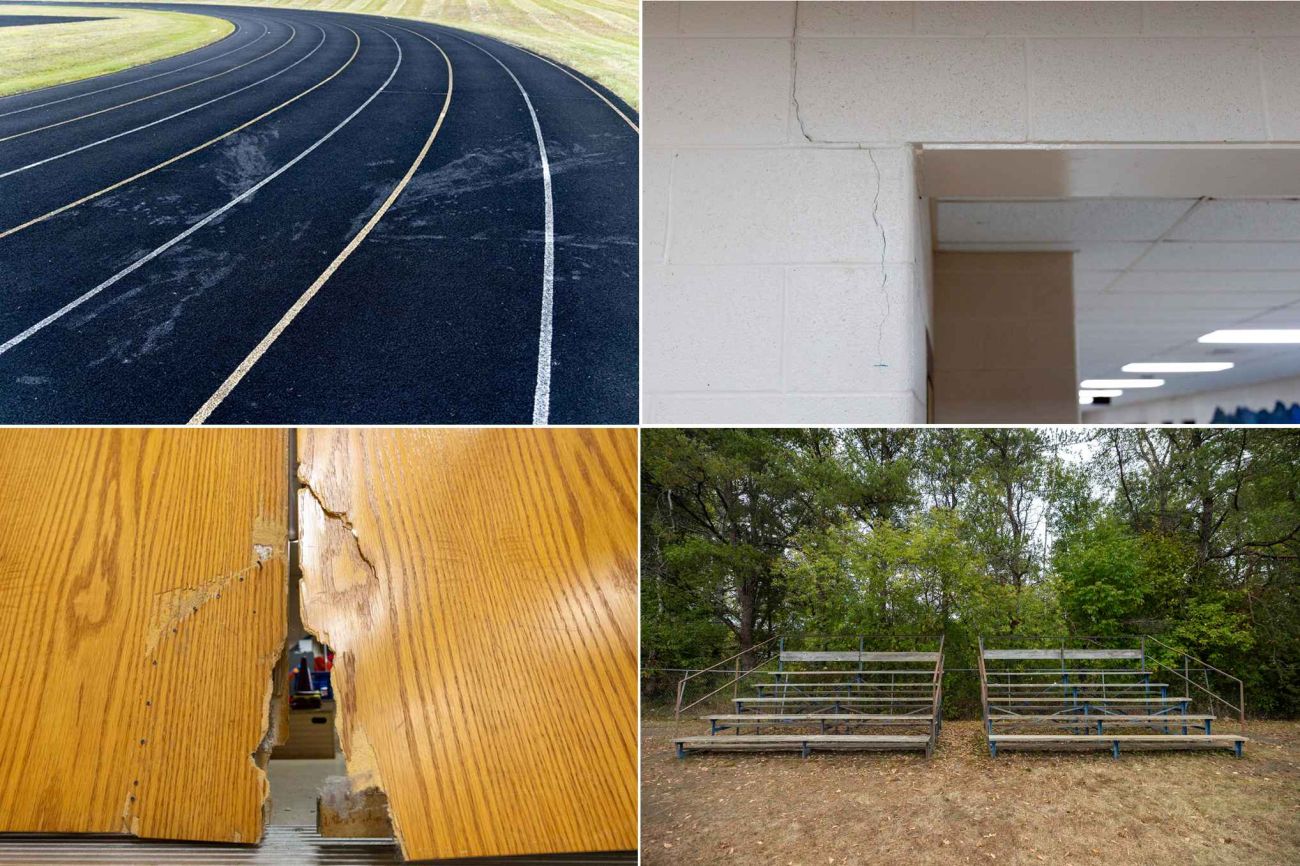

The district is socking away 3% of its budget for repairs, but schools still need to replace heating and cooling systems, remove asbestos from steam pipes, upgrade technology and repair the roof of the community pool, the district informs voters on its website.

It’s not an easy sell. Resident Pat Barrie told Bridge she voted against previous funding efforts because she said they included “a lot of little extras.”

After attending a recent meeting with Hilton, she said she’s “more supportive” of the latest effort but still doesn’t know how she will vote.

What’s at stake

Don Wotruba, executive director of the Michigan Association of School Boards, said the size of the tax, community trust and inflation may all be factors as to why passage rates are down.

Wotruba said many voters may pass public safety tax increases to avoid laying off firefighters, for instance, but know that students will still have school even if they don’t have a new building.

Add in inflation and it’s no wonder the passage rate is falling, he said.

“How do you compete as a school district with a grocery bill?” Wotruba said.

Other factors include skepticism about the district’s spending, personal connections to schools and what else is on the ballot, according to experts.

“People … want to be supportive of the schools,” said Hale Area Schools Superintendent Jeffrey Yorke.

“They also all have to look at their own bottom line. And taxes get tough and to the general community, no matter what it's geared for, it's still a tax to them.”

In August, Hale voters rejected a sinking fund proposal, a pay-as-you-go savings account rather than a loan. In November, the district will try again to propose funds to update a 1998 building that serves 365 K-12 students.

“You… wouldn't go 25 years in your house without looking at maintaining things to the best you could, so it stayed around as long as it was possible, to the best functionality as possible,” Yorke said.

State law limits what schools can fund through bonds, which go to local voters as they are paid for through millage increases.

Allowable uses include construction or remodeling of buildings or athletic facilities, bus purchases, energy conservation improvements and certain technology hardware.

Bonds can’t fund textbooks, computer software, supplies and salaries or repairs and maintenance. Schools can also ask voters to approve sinking funds, which are paid for through millage increases limited to 5 mills per year for a decade.

Sinking funds can pay for some of what bonds are allowed for and can also be used for school security and technology purposes.

Before a bond can be placed on the ballot, it must be approved by the Michigan Department of Treasury, as required in the state Constitution.

Districts often turn to marketing efforts to raise voter awareness.

“A lot of times I'll run across (people saying) ‘Well, the solution is to tighten the development and they can build these facilities,’” said Brett Gillespie, a bond services marketing manager at The Christman Company, who works with school districts to get their proposals off the ground and into the public’s view.

“But that's not the case when roughly 85% of their general fund is going to salaries. That 15% left over is not much at all to do anything infrastructure-wise.”

Wotruba, of the school boards association, said he would tell any school district that their chances of passing a proposal is “pretty small” if they don’t have community input or transparency about how the money will be spent.

There’s also the broader conversation about the value of schools and the challenge of understanding what voters need to see to vote “yes.”

At the Tecumseh meeting, school board candidate Heather McGee said one question she gets from voters is essentially, “Why should voters care if they don’t have kids in the district?”

Hilton, the superintendent, said strong schools make for a strong community.

In Berrien County in southwest Michigan, voters have rejected three bond proposals for Coloma Community School District in the last two years.

“A lot of your voters don't have any ties to school,” Superintendent David Ehlers said. “They don't know anything good or bad about the school in some cases.”

Also in Berrien County, Gillespie said he saw an example of how national politics can rear its head.

Voters rejected a $98 million bond proposal for St. Joseph Public Schools for facility upgrades, school construction and remodeling during the May 2024 election.

A local Facebook group titled “We the Parents in Berrien County” affiliated with the national organization Moms for Liberty, urged its followers to vote no on the bond and alleged a non-profit group advocating for the proposal was funded by George Soros.

The Facebook group also posted several times about other school bonds and millages, called on followers to vote down higher taxes and urged voters to say no to a millage for Lake Michigan College after it hosted a drag queen Bingo event.

Role of competition for students

Schools of choice also may make it harder to pass bonds, said Trina Tocco, director of the Michigan Education Justice Coalition.

Statewide, 1 in 4 students attended a charter school or a district other than the one in which they live during the 2022-2023 school year. If choice students don’t live in the district, their relatives can’t vote in bond elections, Tocco noted.

“School of choice creates constant challenges,” Tocco said. “Because people don't have skin in the game.”

That can create an arms race of sorts where nearby districts have to upgrade facilities — with bond requests — to attract students and families.

“We've got to figure out a solution because unfortunately now we're in a competition in education, right, for students in the area,” said Ehlers of Coloma Community School District.

“And as other districts are upgrading their facilities or have nicer facilities and things like that that attract students, we've got to do something to do ours.”

In Coloma, 30.8% of students left for a different district during the 2022-2023 school year, while 32.3% of the district came from students choosing in, according to a previous Bridge analysis.

Ehlers said he does not think choice is a major factor in why the proposals previously failed.

Some hope?

Districts in Ottawa, Van Buren, Newaygo, Montcalm, Oceana, Midland and Tuscola counties have seen the sharpest increase in school bond rejection rates.

All are Republican-leaning counties. But Democratic leaning counties that supported President Joe Biden in 2020 also are rejecting more bond measures.

Despite the recent downturn in passage rates, there may be reason for optimism among districts hoping to pass proposals after this November: the absence of a divisive competition at the top of the ballot.

Gillespie said that he doesn’t believe the downward trend for school proposal passage during the August primary election is as dramatic as the numbers may imply, due to the lingering effects of the presidential election and the discourse it inspires.

At a recent conference hosted by the Michigan Association of Superintendents and Administrators, The Christman Company cited the political timing of this year’s primary as putting school proposals in a tough spot.

“People right now, they're hypersensitive because of the presidential election,” Gillespie told Gongwer News Service. “Next year being an off year, I think you'll have quite a few districts going out next year, and I think the success rate will be quite a bit higher than it was this year.”

Gillespie said Michigan’s more competitive Republican primary in the U.S. Senate race this August could have contributed to a lower passage rate for school proposals, given a possibly heightened turnout of Republicans less likely to approve bonds or millages at the polls.

The tensions at the top of the ticket, many of which involve education and competing visions for America’s public schools, have a tendency to trickle down to voters deciding on local issues.

Divisiveness and fatigue from a national conversation, however, won’t be the case every year, Gillespie said.

“Next year being an off year, when there won't be a presidential election, I think you'll have quite a few districts going out (and pursuing bonds),” he said. “I think the success rate will be quite a bit higher than it was this year.”

Bridge Capitol reporter Simon D. Schuster contributed to this story.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!