Michigan lags behind other states in pre-K efforts

The education of Jordan Shaw will start a year later because she lives in Michigan.

The Canton girl was in a private preschool program last year as a 3-year-old. But after Jordan’s little brother was born, her parents could no longer afford it.

"Preschool gives them good learning skills. (But) trying to pay for her and (baby brother) Jason, we just couldn’t do it," said her mother, Abena Shaw. We took her out because of the (cost)."

The Shaws weren’t aware of Great Start Readiness classes, and weren’t sure if they qualified. In some states, that wouldn’t be a question.

Five states, including Oklahoma and Florida, offer free preschool for all 4-year-olds. Even some states that limit enrollment to low- and moderate-income households like Michigan have a higher percentage of 4-year-olds in classrooms than the Great Lakes State.

"We did a lot of teaching her at home," Shaw said. "Unfortunately, some kids don’t get that. If you are not doing anything with your child and you’re just letting them watch TV all day, then they need some place that is structured where they can learn."

"We did a lot of teaching her at home," Shaw said. "Unfortunately, some kids don’t get that. If you are not doing anything with your child and you’re just letting them watch TV all day, then they need some place that is structured where they can learn."

Michigan is falling behind in a race that begins with crayons and ends with paychecks.

It’s a race Michigan can’t afford to lose.

Other states are pumping more money into pre-K education than Michigan does, in the belief that preschool now means higher graduation rates and better jobs later.

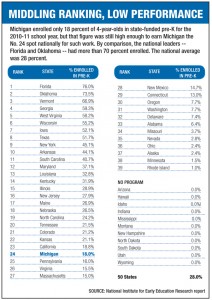

In 2003, Michigan ranked 14th in per-pupil spending among 36 states that provided funding for preschool for 4-year-olds, according to data from the National Institute for Early Education Research. Just eight years later, in 2011, Michigan had plummeted to 33rd out of the 39 states now funding preschool. (Bridge’s analysis adjusts NIEER’s 2011 figures to take into account that about a third of Michigan’s 4-year-olds attend full-day preschool, using funding meant to pay for half-day programs for two children.)

It’s not that Michigan is spending less than it used to on the Great Start Readiness Program (GSRP), the state’s pre-K program for 4-year-olds from low- and moderate-income families. The state provides $3,400 per student, an increase of $100 over funding in 2003.

But other states have increased funding at a much faster clip. Alabama increased per-pupil preschool funding by 43 percent, to $4,544 per student, according to NIEER. West Virginia more than doubled its spending, from $2,486 in 2003 to $5,605 in 2011. Alaska didn’t have a preschool program in 2003, but eight years later was spending $6,855 per enrolled 4-year-old.

Michigan, by contrast, increased funding by 3 percent since 2003. When inflation is taken into account, however, Michigan’s spending is actually a 23 percent decline.

That disinvestment has allowed other states to lap Michigan in the percentage of 4-year-olds enrolled. Michigan ranked 10th in access to state preschool in 2003, according to NIEER; by 2011, the state had dropped to 24th.

"We’re paying a price for that disinvestment," said Larry Good, co-founder of Corporation for a Skilled Workforce, in Ann Arbor. "There are enormous economic implications."

States to south exceed Michigan

Bridge studied the preschool practices of a dozen states that have made significant pre-K enrollment gains in the past decade even through tough economic times.

Successful programs in other states have some similarities from which Michigan could learn. For example:

* Pre-K is an important part of school aid formulas. In Michigan, K-12 school aid funding grows as enrollment grows. But with preschool, funding is set, and that funding determines how many kids get access to preschool. In states such as Iowa, West Virginia, Oklahoma and Maryland, the school funding formulas consider enrollment needs each year – so funding grows (or, conceivably, shrinks) with demand.

* Full-day pre-K programs increase participation, and universal access programs really increase enrollment. Georgia was the first state in the nation to offer universal public pre-K in 1995 – since then, Iowa, West Virginia, Oklahoma and Florida have joined Georgia.

* Growth by partnering with providers beyond traditional school systems. Arkansas achieved 38 percent enrollment growth in the past decade, with a program where only 55 percent of those preschool students are in public schools; the rest of the students are in classes run by private and nonprofit providers. Michigan has a GSRP competitive grant program for that purpose, but only about 10 percent of the state’s preschool funding goes to private providers.

Sooner State sets the standard

The leading state in early childhood education is Oklahoma, where about 75 percent of 4-year-olds are enrolled in state-funded, free, universal-access preschool. When children enrolled in federally funded Head Start are counted, 88 percent of Oklahoma 4-year-olds are in taxpayer-supported preschool. By comparison, Michigan has 18 percent of its 4-year-olds in state-funded preschool, and 34 percent in any kind of taxpayer-supported pre-K.

Universal-access pre-K in Oklahoma was pushed not by education groups, but by a consortium of business leaders and conservative legislators.

Researchers from Georgetown University found that, everything else being equal, 4-year-olds in the Oklahoma program scored better on a letter recognition test (an indicator of later reading success) than those who didn’t enroll.

"Parents are the first, best teacher for their child, but we see value in pre-K programs," said Tricia Pemberton, spokeswoman for the Oklahoma Department of Education.

The preschool program is wildly popular among Oklahoma families. "Pre-K is not mandated, but if we have 20 classrooms serving pre-K, we could start probably four to six more tomorrow – and if they were full day, probably eight," said Lance Crawley, chief financial officer for Deer Creek Public Schools, a suburban district outside Oklahoma City. "We’re turning people away."

The program began as an effort to assist children born into poverty, especially Oklahoma’s large Native American population. But it has morphed into an economic engine for both families and schools. Families are saving about $500 a month in private preschool bills by enrolling their 4-year-olds in the state program, Crawley said. Meanwhile, the schools receive 30 percent more money from the state for a child enrolled in full-day pre-K than they do for K-12 students. (In Michigan, schools get 7 percent less for full-day pre-K students than K-12 students, but for the majority of 4-year-olds, who are in class for a half day, schools get 53 percent less.)

Although the state budget is tight, there is no movement in Oklahoma to pare back the universal access pre-K benefit.

"If anything, there’s more emphasis on it," Crawley said. "Families love it. Kids love it. Their brains are like sponges at that age."

On outside looking in

Jordan Shaw celebrated her birthday last week. She’s now 4, the age when many poorer children are in taxpayer-supported preschool, and wealthier children are in private preschool; an age when almost all children are in preschool in Oklahoma and Florida.

But while those children head into classrooms, Jordan will spend her days at the home of their pastor’s mother.

"Kindergarten is free," Abena Shaw said. "Let them have a place to learn (at preschool) without it having to cost so much."

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!