In Las Vegas, firms pitch mass-shooter security to schools. Does it work?

- After the 2021 Oxford High School shootings, state lawmakers ramped up funding for school safety technology

- Superintendents said they wade through waves of vendor pitches to find the right safety options

- One expert said industry insiders consider Michigan to be a state that has opened its wallet wide for enhanced security

LAS VEGAS — A conference this week at the Tropicana Casino on the Las Vegas Strip is the Detroit auto show of school security gadgets.

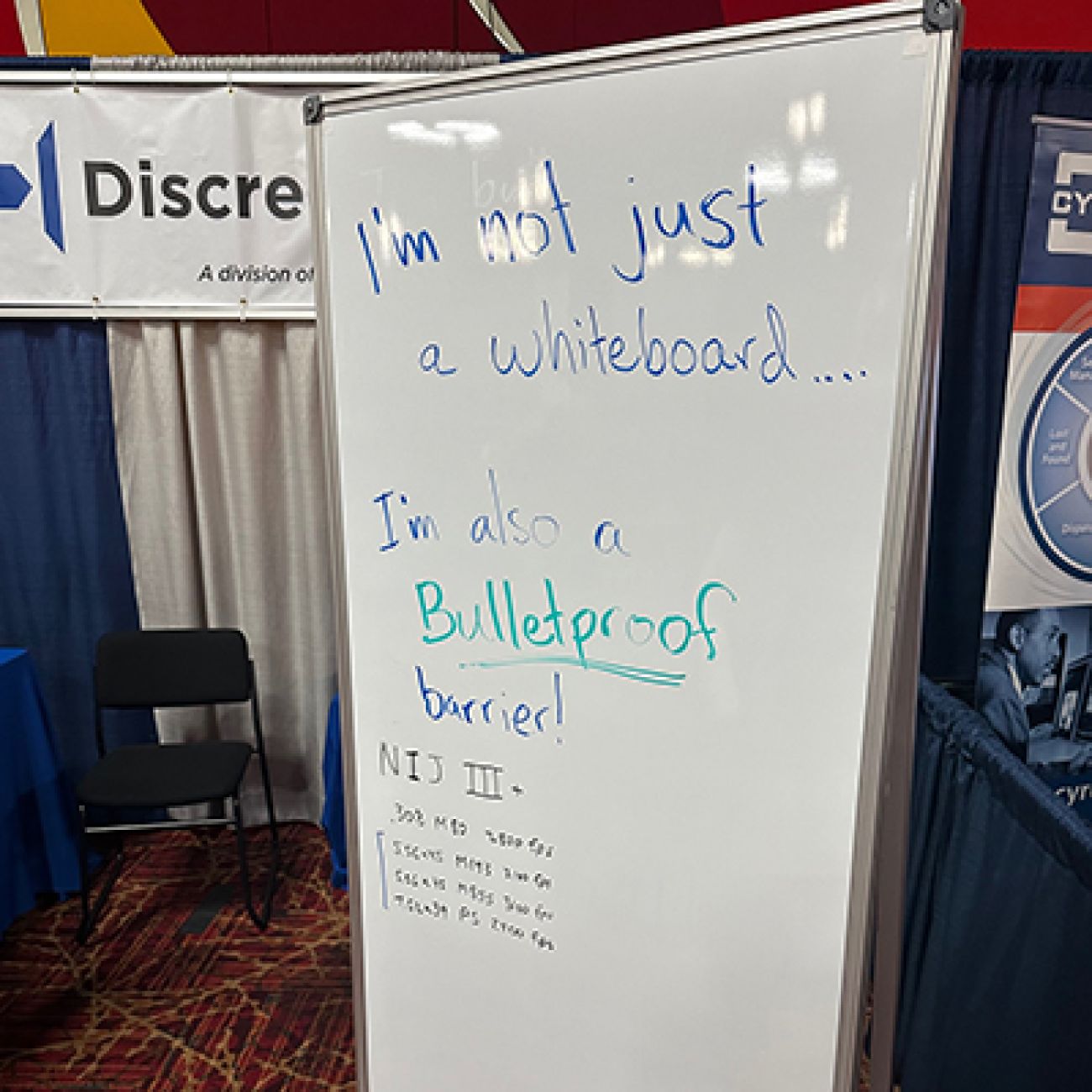

Here, schools could find bullet-proof whiteboards and quick-set tourniquets, robotic dogs to confront active shooters and the latest facial recognition and artificial intelligence systems.

Organizers bill it as the largest school security gathering in the world, with more than 1,400 attendees from every state in the nation, and almost 100 vendors. On Tuesday, Jesse Butler walked past booths looking for ideas.

Related:

- New report provides safety recommendations for Oxford High after shooting

- Michigan schools race to increase safety through high tech, mental health

- Judge to decide if teen Oxford shooter can be sentenced to life without parole

Butler is director of facilities for Matrix Human Services, which enrolls about 1,600 Head Start students in buildings across Detroit. Their buildings already have security cameras and a room-barrier system called TeacherLock, Butler said, but the organization wants more safety measures.

One booth caught Miller’s eye — a company that provides bullet-proof film to apply over existing school windows. Butler stopped and chatted at a booth sponsored by Motorola, where representatives were pitching an integrated camera and alert system.

Miller asked if the system could also incorporate body cameras for school employees. No problem, the vendor said.

Matrix has $250,000 allotted for security purchases in 2024, Butler said, and the Las Vegas conference was a one-stop shop to make young Detroit preschool children safer.

“With the climate around the country,” Butler said, “everyone is vulnerable.”

Flush with state funds targeting school security and facing calls from worried families, Michigan schools are sorting through a myriad of security technologies being pitched by what has become a burgeoning $3 billion-dollar industry.

But some experts who study school violence, as well as some in the industry itself, are questioning whether that money is being spent wisely, with the bulk of investment currently going toward high-tech systems meant to identify or slow an active shooter, rather than prevention.

Today, school security is focused on “a lot of hardware (and) flashing lights,” said David Rogers, marketing director for Raptor Technologies, a school data and security company. “It’s going to be expensive. And the minute they install it, it's going to be out of date.”

The Oxford impact

An Oakland judge heard testimony Thursday to decide whether Ethan Crumbley, the teen who killed four classmates and injured seven others at Oxford High School in November 2021, should receive life in prison without parole.

Since the shooting, state grants totaling up to $335 million have been allocated to Michigan public schools for school security improvements. That’s a seven-fold annual increase since the last pre-COVID school year, 2018-19, when the state earmarked $25 million for school security technology and equipment.

While state-by-state security funding data isn’t available, Sean Burke, president of the School Safety Advocacy Council, a national school safety group, said that industry insiders consider Michigan to be a state that has opened its wallet wide for enhanced safety measures.

One example is Vassar Public Schools, a rural Tuscola County district of 900 students east of Saginaw, which decided to invest in school security upgrades in 2022 after the school shooting in Oxford, 40 miles away.

“That really hit us hard,” Vassar Superintendent Dorothy (Dot) Blackwell told Bridge Michigan. “When that happened, all the superintendents in the area started talking about security.

“I got a phone call from a parent saying, ‘Dot, what are you doing to make sure my child is protected?’ We’ve got secure entrances, and we train (active shooter drills) and we have cameras. When the state offered grants, we applied for every grant we could (for security enhancements).”

Using state funds that allocated up to $160 per student to districts for security measures, Vassar signed a five-year contract with ZeroEyes, a firm that uses AI technology and already-installed cameras in school buildings to detect guns. When the system detects something that it believes is a weapon, an alert to a national control center staffed by ex military and police officers, who decide whether to alert school officials and local police.

The company says schools are alerted within 3-5 seconds of a gun being detected.

ZeroEyes also has a system in Oxford, installed after the 2021 shootings.

Blackwell said she received alerts from ZeroEyes on her phone in May, when, on senior prank day, several seniors brought Nerf guns to school.

While the toys were not a danger, the alerts made Blackwell more confident that the high-tech system would detect a real gun.

“I consider it an insurance policy,” Blackwell said.

ZeroEyes officials demonstrated the system to first responders and administrators from nearby school districts in June, in an all-purpose room at a Vassar school building.

Watching the June presentation was Holly Area Schools Superintendent Scott Roper. Even though the 3,100-student northern Oakland County district already has extensive security measures, from locked entrances and classroom door barricades, to cameras, school resource officers and armed security guards, Roper is on the lookout for enhancements.

“It’s our responsibility to review different options,” Roper told Bridge Michigan.

School districts have to sort through a lot of choices. School leaders are inundated with salespeople trying to sell security products.

Stacy Price, superintendent at Tahquamenon Area Schools, a sprawling 1,500-square-mile, one-school district in the eastern Upper Peninsula, said she receives promotional emails about school safety products at least three to four times a week.

She feels the same way about safety upgrades as she would if she had a broken refrigerator in her home: she would research before she buys a new one.

“It’s taxpayer dollars that they entrust with me so I need to be able to spend that as best as I can.”

The majority of current school security spending across the country is on hardening buildings, camera systems and shooter detection technology, said Amy Grosso, a director at Raptor Technologies, which supplies a wide swath of security and management systems for U.S. schools.

American schools tend to “focus on products for after the shooting starts,” such as alert gunshot detection and alert systems, Grosso said. “And we keep doing the same thing, and the rates (of school shootings) just keep going up. So that tells me one thing: We need to start doing something different.”

Security impact is unclear

Even experts aren’t sure the billions of dollars spent on school security has been effective. Frank Straub is senior director of violence prevention for Safe and Sound Schools, a nonprofit school safety advocacy and research group, and co-director of a Michigan State University pilot program that is designed to identify and support students who are at-risk of committing violence.

He has studied school shootings and instances where someone who had intended to carry out a school shooting was stopped before anyone was injured or killed. He told Bridge there isn’t a lot of research on specific technology preventing shootings and that it is challenging to measure things that didn’t happen, like when safety measures discourage a potential shooter.

Straub said “there really isn't conclusive evidence that target hardening necessarily prevents school attacks,” but there hasn’t been an attack yet where an individual has gone into a classroom “that was properly secured,” such as with a locked door.

“So I think there is merit to suggest that appropriate locking devices on classroom doors that are appropriate and operable by persons with disabilities should be carefully considered.”

If schools have doors with glass windows, he said schools should consider using a film on the window to obstruct the view inside or use shatterproof glass. Cameras throughout the school or at a school entry can be helpful too, but only if someone is able to monitor the footage in real-time. Otherwise, as Curt Lavarello, executive director of the School Safety Advocacy Council told Bridge at the Las Vegas conference, “all you have is a really nice picture of the shooter you can look at later.”

Showgirls and tourniquets

In Las Vegas on Tuesday one of the speakers was Ken Mueller, former director of student services at the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District, where an 18-year-old fatally shot 19 students and two teachers, and injured 17 others at an elementary school.

Mueller, who left his position under pressure months after the massacre, acknowledged the irony of standing in front of a projection screen that read, “Preventing tragic incidents before they happen.”

“I can’t tell you how to prevent it,” Mueller told the crowd of security professionals and school administrators. “I didn’t.

“I didn’t know who the kid was,” Mueller said. “I’d never heard his name. How could a person be this evil and we not know anything about him?

“You always think, what more could we have done?”

A few yards away, about 100 vendors were doing their best to answer that question with their own sales pitches. At an opening night reception, two purple-plumed showgirls greeted attendees at the door beneath a school safety sign. Inside the saleroom, Diet Pepsi was $6 but the cabernet was free. One vendor was holding drawings for bottles of whiskey near a video monitor flashing headlines from school massacres.

There were multiple companies selling bulletproof doors, along with another marketing hardened partitions that could be added to desks that students could duck behind, and bulletproof whiteboards that sell for $4,000 to $9,000 apiece depending on size.

Two vendors pitched medical equipment meant to limit bleeding until emergency personnel can arrive. Another was trying to sell a gadget meant to break glass in classrooms where windows don’t open, allowing students to escape a shooter.

There were booths for companies with names like SecureTech and Omnilert, and several companies marketing behavioral assessment databases meant to help schools recognize and track students who may be dealing with issues that could lead to violence.

Centegix demonstrated panic buttons school employees can wear around their necks or connect to name badges. Rudyard Area Schools in the Upper Peninsula will use the technology this school year.

Superintendent Tom McKee told Bridge he wanted to find a way to ensure staff in his quarter-mile-long school building could communicate with each other in case of an emergency.

If a staff member calls for a lockdown, the public announcement and lights system will communicate to others that it’s time to barricade doors in the 625 student building.

McKee said he wanted to tour a school that has the technology but he says he couldn’t find another school with the technology in the state.

Back in Vegas, there were vendors demonstrating walk-through and wand metal detectors. Eviden, a Texas-based tech firm, had an elaborate display for a product called VYZE, which uses facial recognition and artificial intelligence to recognize individual students and even track license plates of cars pulling up to schools. In the video demonstration, the system alerted school officials that a student was smoking near a school sports stadium.

“There’s billions in this industry,” said Lavarello, of the School Safety Advocacy Council, the organization hosting the convention. “There are companies chasing that money.”

The first National School Safety Conference, in 2004, drew 90 people, Lavarello recalled. This year, there were more than 1,400 attendees and almost 100 vendors, with several dozen more vendors turned down because there was no more room in the conference center.

Lavarello, who has served on White House commissions on school safety following massacres at Columbine, Virginia Tech and Sandy Hook, said high-tech gadgetry isn’t the answer to stopping the nation’s school shooting crisis, at least not on its own.

“Schools want a fix-all,” he said. “There is a lot of great technology out there. But you can have all the technology in the world to stop people from entering buildings and it won’t work … without a good safety plan.” State and federal funding for school security “is like a roller coaster,” Lavarello said. “A shooting occurs, funding goes up, and then it trickles down. We're a very resilient country, so we bounce back from these tragedies very, very quickly. And then there’s another shooting and (funding) goes up again.”

And when funding goes up, superintendents start getting sales calls. Greg Nyen, superintendent at Marquette-Alger RESA in the Upper Peninsula, said it’s typical for vendors to inundate districts whenever something new is pushed in education, whether it’s about the best way to teach reading or the newest way to stop active shooters.

“With (states) allocating more and more resources toward school safety, there are more and more for-profit businesses, vendors that are looking to get their slice of the allocation,” Nyen said.

Burke, of the School Safety Advocacy Council, described a kind of gold-rush mentality.

“You have companies that have never been in the school industry, that have worked in banking or medical industries, who are now retrofitting their products for schools because there’s money there,” Burke said. “And you have big companies that haven’t been in school security who are buying smaller school security companies and trying to get in on the money.”

On the Vegas vendor floor were several companies that had never before sold any products to schools, and others that were marketing products originally designed for other fields, such as wearable panic buttons and devices to stop bleeding.

Michigan’s Stryker Corp, which focuses primarily on medical industry products, recently purchased Vocera, a company that produces a wearable alarm and communications device. Designed for the health care industry, Stryker was at the Las Vegas convention marketing Smartbadge to “connect and protect your staff and students.”

Stryker representatives at the conference declined to comment on the product.

“One of the biggest mistakes of schools is relying on gadgets instead of a comprehensive safety plan,” Burke said. “There’s no amount of money you can spend to make your school safe if you’re not doing the simple things like locking your doors.”

Do simple things first

Since most school shootings last five minutes or less, Burke said schools should focus security spending in two areas: Equipment or services that slow down the shooter, such as locked doors and bullet-resistant coatings on windows, and equipment or services that get police to the scene faster, such as gun detection systems and well-marked doors and floor plans.

Schools don’t have to spend a fortune to do that: Locking all classroom doors when students are inside, and “Going to Home Depot and buying big numbers and putting them on classroom doors,” to help first responders identify the classroom being attacked will both help, Burke said.

About one in four public schools did not have classrooms where doors can be locked from the inside during the 2019-2020 school year, according to survey data from the National Center for Education Statistics. (That was also a problem identified at Michigan State University after it was attacked by a gunman in February.)

Physical security is only part of the equation, said MSU’s Straub. It’s also exceedingly expensive for schools to retrofit old buildings to add many security features.

Straub said schools should also invest in positive school cultures, school counselors, therapists and psychologists, as Michigan lawmakers are now doing by heavily investing in student mental health.

“I think there's been a lot of money made available for physical security enhancements in schools,” Straub said. “And so as a result of that, superintendents are taking advantage of it. I also think that when we talk about investing in a student that has significant behavioral concerns, it is just that: it's an investment. It is time intensive. It is challenging.”

But if leaders don’t invest in these students, Straub said, “we’re increasing the risk for violence.”

One example: Holly Superintendent Roper said he’s adding support dogs at the high school next year and trying to increase the number of student organizations to “get kids out there, doing different things with their peers.”

Grosso, of Raptor Technologies, is working on a behavioral analysis system that helps identify students who have had some struggles, such as dropping grades or parental divorce, that may not rise to the level of attention of school administrators. The idea: to ward off problems before they become serious.

The U.S. Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center studied 41 school violence incidents that happened from 2008 to 2017. What they found is that there is no single, tidy profile of a student attacker; they varied in age, grade level, academic performance and social characteristics.

What researchers did find is that most attackers used a firearm and most had “experienced psychological, behavioral, or developmental symptoms.” The group recommended that schools create multidisciplinary threat assessment teams that include school personnel and law enforcement.

Butler, the Head Start facilities administrator, said he’s coming back to Detroit with ideas for how to enhance security for children and staff.

Money shouldn’t be a problem, he said. Vendors told him that there are plenty of federal grants.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!