Charter schools: Different road, but still bumpy

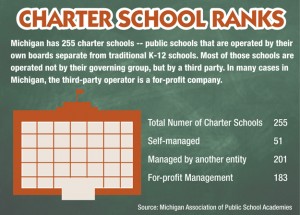

Nearly 20 years into the experiment, public-school academies -- charter schools, as they are more popularly known -- would appear a rousing success. An enthusiastic Michigan Legislature, as part of a comprehensive reform package, lifted the state cap on charters late last year. The charter ranks, now at 255 schools, can start growing next year and operate without a state cap in 2015.

The schools, which already educate almost 120,000 students at an average of 470 students per school, play a major role in Gov. Rick Snyder’s education philosophy, which emphasizes parental choice and market forces to drive improvement and innovation. But since the charter experiment started in 1993, data collected on both the state and national level suggest they are doing no better at educating students than are traditional K-12 public schools.

An analysis of test-score data done for Bridge Magazine by Public Sector Consultants shows charters falling along roughly the same achievement lines as traditional public schools, for both better-off and less-advantaged students.

An analysis of test-score data done for Bridge Magazine by Public Sector Consultants shows charters falling along roughly the same achievement lines as traditional public schools, for both better-off and less-advantaged students.

While many charters produced outstanding results on statewide tests of academic achievement, taken on average, their test results were at or below statewide averages. In fourth-grade reading, math and writing tests, the statewide averages for traditional-school students ranked as meeting or exceeding standards were 84.8 percent, 91.8 percent and 48.2 percent, respectively. Charter-school students scored 76.8 percent, 87.6 percent and 37.7 percent on the same tests.

In eight-grade reading, math and science, traditional-school students meeting or exceeding standards were 82.3 percent, 78.8 percent and 78.9 percent respectively, while charter students were at 77.6, 67.8 and 68.7 percent.

WMU prof: Charters don't beat traditionals

Those results, experts told Bridge, are to be expected.

“There have been close to 80 different studies now, and (those results) have been pretty consistent,” said Gary Miron, a Western Michigan University professor whose work has concentrated on school choice. Last year, he gave testimony to Michigan legislators considering the charter cap. He told them, in part:

“While I looked favorably upon the original intent of charter schools, I am increasingly concerned that after two decades and substantial growth, the charter school idea has strayed considerably from its original vision. A growing body of research as well as state and federal evaluations conducted by independent researchers continue to find that charter schools are not achieving the goals that were once envisioned for them.”

Miron went on to lay out why he thinks the schools have fallen short of their lofty founding goals of driving educational improvement through innovation and competition: They lack effective oversight and accountability. They’re chained by the current emphasis on testing and specific performance standards. Privatization and profit-seeking drain dollars away from instruction.

The cap was lifted anyway. Miron says to expect “more of the same.”

So, more charter schools? Certainly. But Dan Quisenberry, president of the Michigan Association of Public School Academies, says not to get excited.

"People use words like 'explosion,'" he said. "That's not going to happen. "We might see 10, 15 new schools a year. We'll see the charter mechanism for what it was designed to be -- for opportunities to innovate in education."

Miron says more charters will simply mean that dwindling education dollars will be stretched further, and points to Detroit charters as an example: "They should be doing better, but they're not. So now, instead of one struggling system, we have two. Instead of fixing our problems, we're starting a whole new system, and the new system isn't better."

To charter-school advocates, of course, the picture is very different.

Quisenberry doesn’t “automatically accept the premise” that charters aren’t as good as their traditional equivalents.

“There is success, we are seeing what was hoped for,” Quisenberry said. “Does it mean everyone is 100 percent proficient and headed to Harvard? No, but when you look at (the role of charters in) responding to academic failure, we’re absolutely having success.”

Of districts with three or more operating charters, Detroit stands alone with 47, followed by Grand Rapids with 10, Marysville with 9, and Flint, Southfield and Lansing, with 7 each.

There are outliers in the data, which all sides freely acknowledge. Some of the best schools in Michigan are charters, Miron said, adding, “I have been an evaluator in nine different states. I have done and seen a whole lot. In every single state, we see inspiring charter schools, schools that make me want to teach again. They exist. They are the anecdotes that get lifted up. It complicates the policy debate.”

What complicates it, Miron said, is that you shouldn’t base state educational policy, particularly one with such profound implications for the future of publicly funded education, on the outliers. And a few exceptions, heartening though they may be, don’t justify what he describes in a metaphor incorporating highways. If you have potholes on Interstate 94, you don’t deal with them by paving a parallel highway a few miles to the north, taking money from the existing one to build the new one. Then you have two bad highways.

Many of the studies that have looked at charter-school performance have used the same model as that described by Phil Gleason, senior fellow at Mathematica Policy Research, in a study done for the U.S. Department of Education. To compare schools at the middle-school level, they chose subjects who had entered lotteries for highly sought-after schools, and followed both winners and losers. The schools covered a range of socioeconomic levels. Student results were measured by state test results, and by surveys of both students and parents.

“Overall, we found that the charter schools didn't do on average systematically better or worse than the kids who lost the lotteries,” Gleason said.

In general, Gleason said, the poorest students, with the lowest achievement levels, were the best-served by charters, but that the difference between charter and traditional-school results disappeared as subjects rose in socioeconomic status.

“Where we did find a set of outcomes where there were significant impacts (was in) student satisfaction, and that of their parents,” Gleason said. “It is kind of interesting that in a number of studies, parents are happier than students.”

U-M expert: Charter effects largest on poor minorities

Susan Dynarski, a University of Michigan professor currently at work on a multi-year study of Michigan charter results, worked on a similar study in Massachusetts for the Boston Foundation. There, she said, in urban areas, among poorer and non-white students, charter-school lottery winners showed “large and positive” effects, as compared to the lottery losers who stayed in traditional schools. And the good effects improved over time, to the point that “three years of going to a charter erases the black-white (achievement) gap.”

But outside the urban areas, where school populations are generally better-off economically, results dropped to zero or even negative, Dynarski said.

Miron says such results track along another line he’s noticed as a researcher: Studies of charter performance done by the federal government or state agencies show more negative results, while those “for think tanks or the Gates Foundation (are) more positive.”

With the lifting of the cap in Michigan, charter-school advocates hope even more contenders will help elevate charter results. Quisenberry says the schools are here to stay:

“A static system that only allows for a single provider doesn't work anymore,” he said.

His comments reflect a newer argument for charters – choice for choice’s sake.

“Public funding of education is for students,” said Quisenberry. “With Proposal A, we’ve decided to let parents allocate that money. We're not taking (students out of traditional public schools), parents are. They have a choice.”

Staff Writer Nancy Nall Derringer has been a writer, editor and teacher in Metro Detroit for seven years, and was a co-founder and editor of GrossePointeToday.com, an early experiment in hyperlocal journalism. Before that, she worked for 20 years in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where she won numerous state and national awards for her work as a columnist for The News-Sentinel.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!