In 1978, a teen opened fire at Lansing Everett. It has lessons for Oxford.

LuAnn MacQueen was a first-year teacher at Lansing Everett High School back in February 1978, working in the math lab.

Becky Dodge, a junior, had just left a typing class down the hall.

Sophomore Mike Poole was exiting his class two floors below.

Moments after the day’s final school bell, Roger Needham, a 15-year-old sophomore, left class and headed for his locker. A pale, slight boy, described as a loner, Needham had been teased throughout the year for wearing a Nazi pin. He didn’t like it.

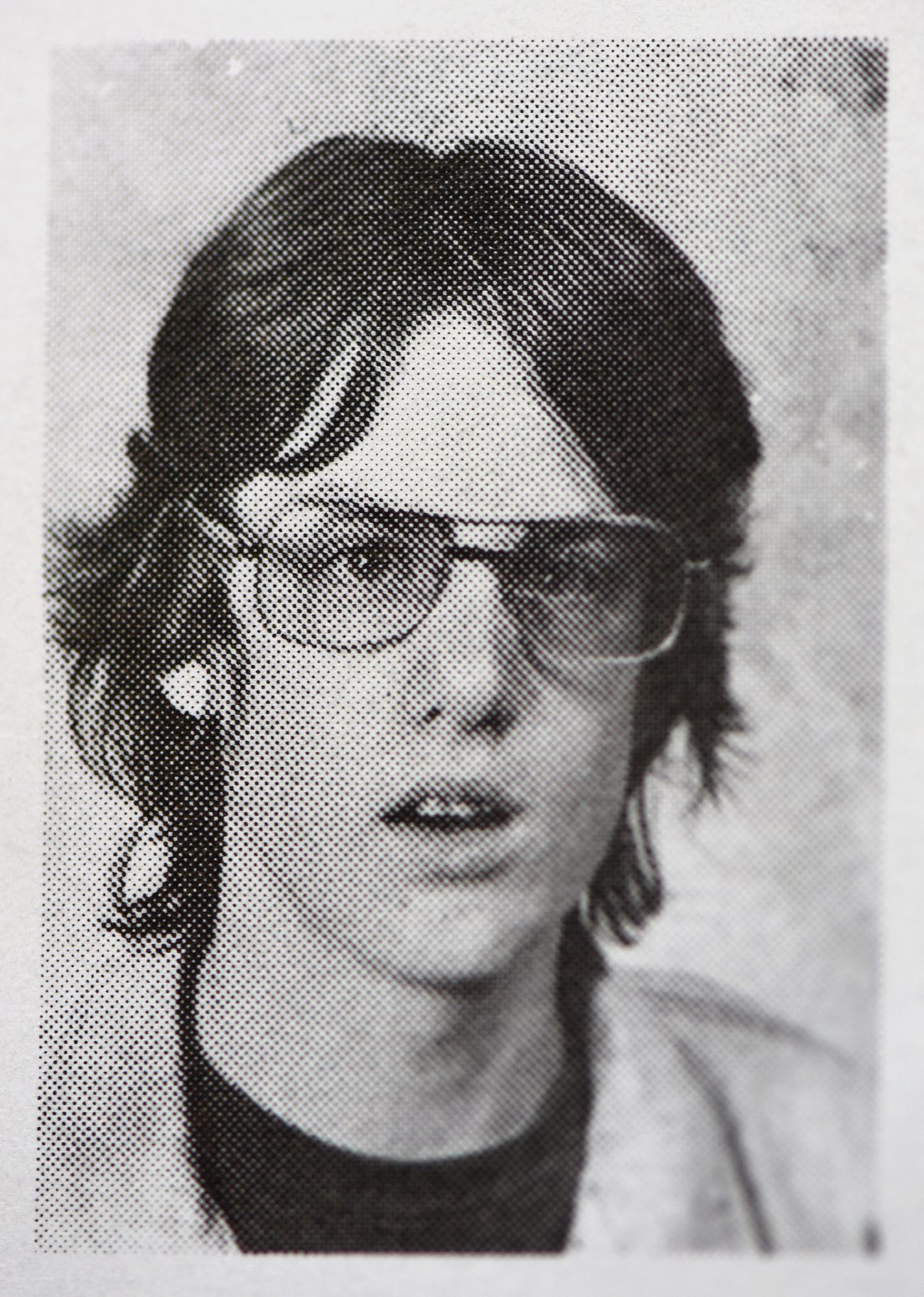

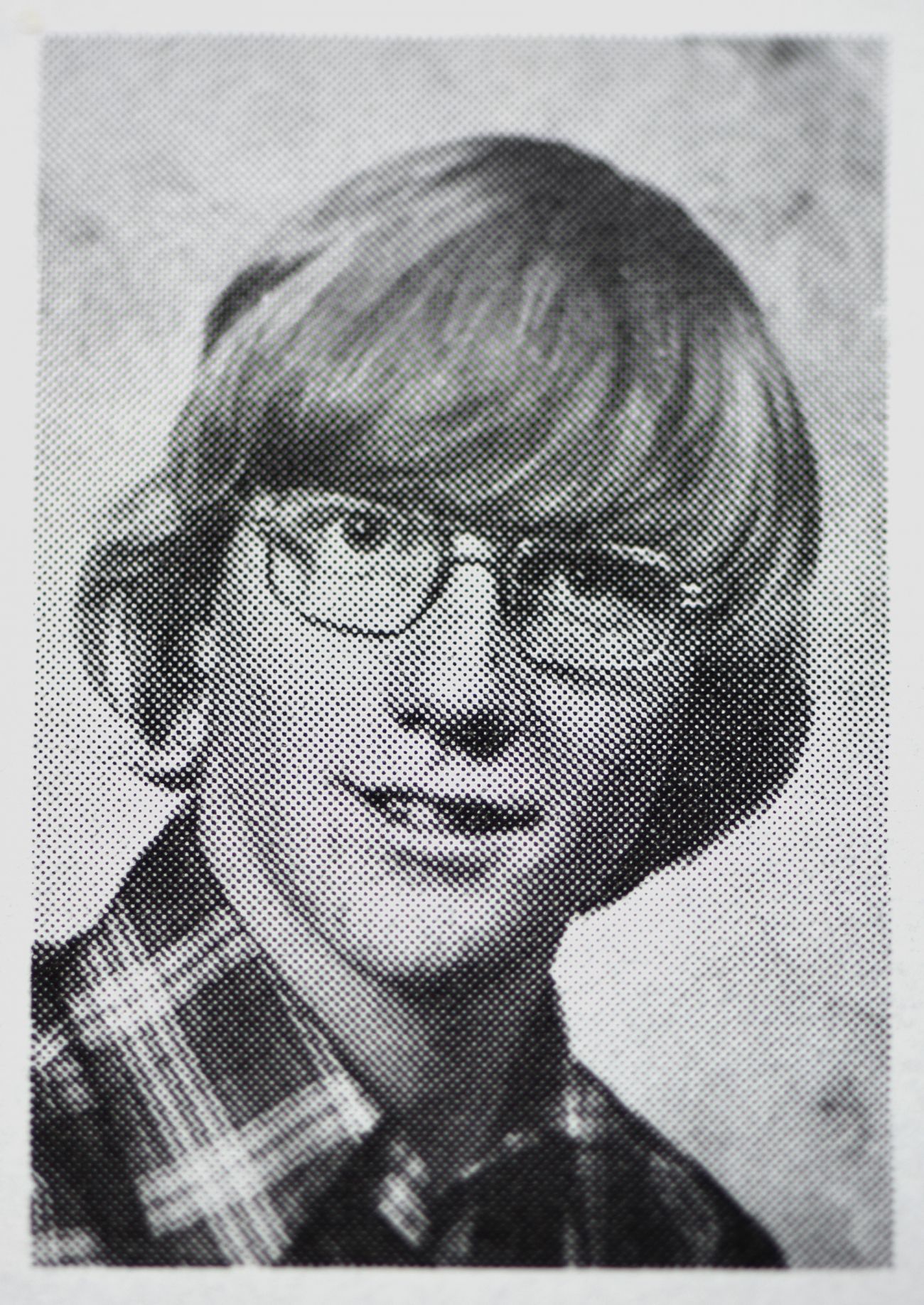

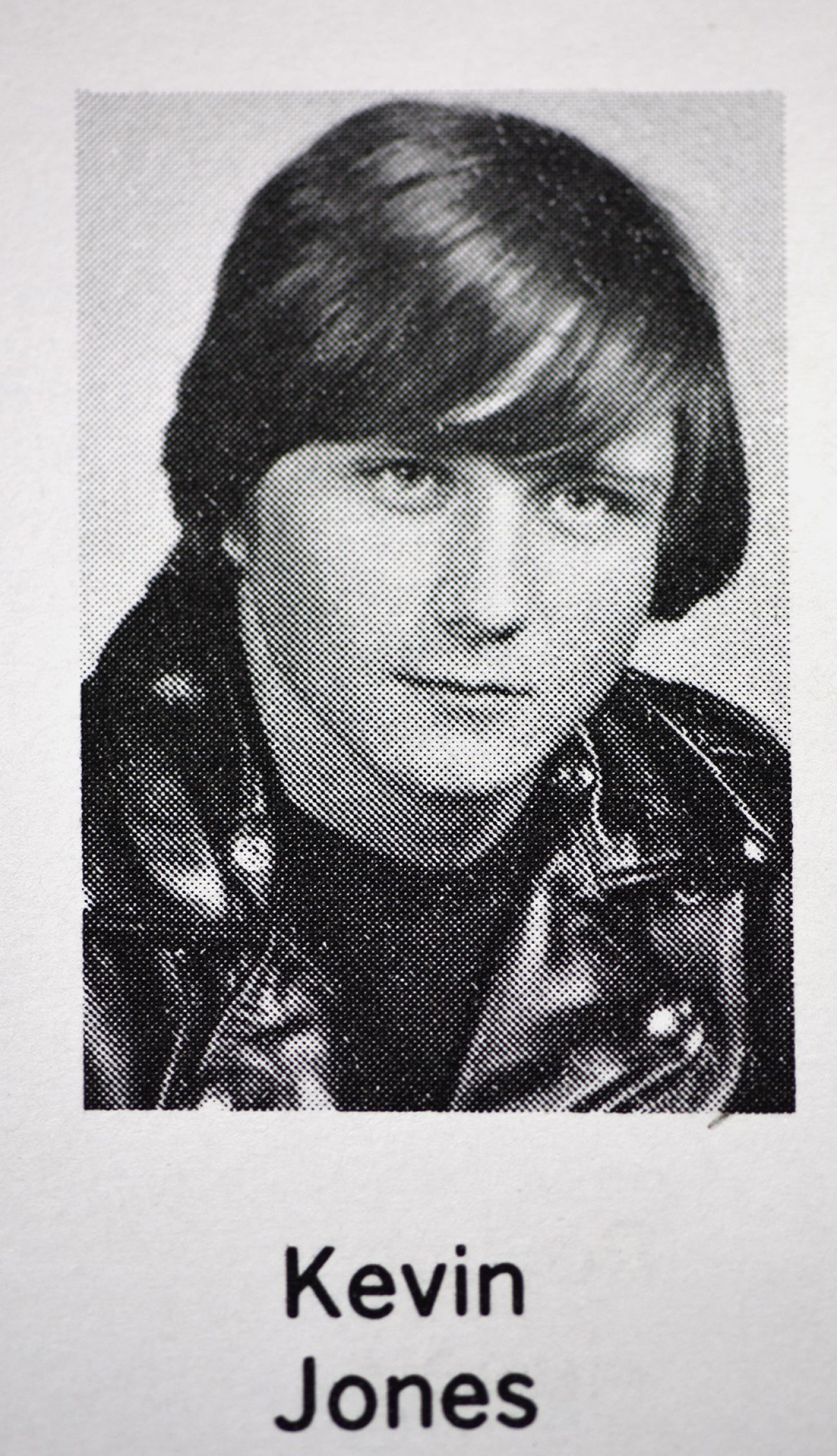

In the crowded hallway, Needham pulled out a Luger-style .22-caliber pistol and fired, grazing the scalp of a classmate, Kevin Jones, 16. Jones ducked as Needham fired a second time; this time the bullet struck 15-year-old Bill Draher in the jaw. Needham then fired once more at Draher’s head.

Related:

- After Oxford shooting, Michigan Dems seek to bar high-capacity magazine sales

- Oxford school shooting: Sandy Hook mom urges mental health focus

- Bloody drawings, a cry for help and Oxford’s choice before school shooting

As Draher lay fatally shot, the gunman approached a teacher and handed him the pistol, a knife and a box of ammunition, according to a 2001 account on the shooting and its aftermath by the Tampa Bay Times.

“Here,” he said, “I give up.”

A path to healing

Though more than four decades have passed since gunshots shattered the rhythms of an ordinary winter day, the Everett teacher and students who recently spoke to Bridge Michigan agreed on one point: those brief moments of terror would alter their sense of the world.

Poole, the Everett sophomore, said he lost more than a friend that day.

“It destroyed my sense of security at school, and I think for everybody who went there,” he said.

“Anybody that’s dealt with the trauma of a gunman coming down the hallway, or running outside because someone has a gun, I think that puts the fear of guns in your blood forever. I don’t know how it couldn’t.”

It’s a trauma now being processed by a new round of survivors of school violence. The Nov. 30 mass shooting at Oxford High School killed four classmates — Hana St. Juliana, 14, Madisyn Baldwin, 17, Tate Myre, 16, and Justin Shilling, 17 — and injured seven others (including a teacher).

As in the Everett case, a 15-year-old boy has been charged in the Oxford shootings.

It was, according to the Education Week 2021 School Shooting Tracker, the 29th school shooting of 2021. The fact Education Week has such a tracker speaks to how endemic U.S. school violence has become.

University of Michigan psychology professor Sandra Graham-Bermann told Bridge that school shootings leave a psychological imprint that can linger for a lifetime, though she said most students eventually adjust.

“We learn to live with the sadness and go forward,” she said.

Graham-Bermann said that for many of the Oxford students, that recovery may not be possible without longer-term support.

“Certainly, (counseling) programs at schools are great. But if time goes by, a month, six weeks later and a person is still experiencing symptoms, not being able to go to work or to school, or unable to sleep, then they are going to need professional help.”

Officials from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on down to local school leaders and therapists across Oakland County are making mental-health, financial and other resources available to people throughout the Oxford community.

The urgent and comprehensive support in Oxford is built from brutal lessons learned from earlier tragedies at schools like Lansing Everett. Another tracker, kept by the Washington Post, counts more than 278,000 U.S. students who have experienced school gun violence since the Columbine High School massacre in Colorado in 1999.

Consider this difference between Oxford in Everett: Back in 1978, there was apparently no organized response to support students like Poole after his friends were shot. He told Bridge he doesn’t recall much outreach and added that, from his perspective, he doubts it would have done much good.

“I’m sorry to say, but I don’t think any counselor is ever going to fix all that.”

Studies show most survivors of mass shootings show resilience when provided generous support, particularly when they feel connected with their community. That may be taking place in Oxford, where a series of community vigils and memorial events are giving teens, families and others in the region opportunities to gather and mourn and, it is hoped, to heal.

For the Everett survivors interviewed by Bridge, Oxford and other shootings trigger a rush of memories from their own experiences. When the Oxford attack made news, the thoughts of Becky Dodge, the girl leaving typing class four decades ago, drifted back to the ambulances that descended on her high school.

Dodge, whose name is now Becky Qashat, said she’s moved past the 1978 shootings — just as U-M psychologist Graham-Bermann said most do — though flashes of that day still bubble to the surface.

For first-year Everett teacher MacQueen, now Murray, Oxford raised fresh fears about the safety of her own children, three of whom now attend a high school southwest of Lansing.

“It just causes you as a parent to be on high alert as to how easy that can be,” she said.

A shock on school grounds

When the Everett shootings happened, Murray said the gunfire seemed surreal to students and staff. Unlike the grim standard procedure today, there were no lockdown drills at Everett, no active-shooter training. No mass exit practice. And no armed officers in the hallways. They were utterly unprepared.

What would be the point?

“People didn’t know what to do. We never had drills for that. It was never brought up because it had never happened before,” said Murray, who retired from Lansing Everett in 2015 after a 38-year career.

“Back then, we knew there were shootings, but that didn’t happen at schools. It just didn’t happen.”

After the Oxford shootings, authorities praised students and staff for their disciplined response, including barricading themselves in classrooms and reducing the number of people exposed to the gunman.

In 1978, Everett students had no such training. Becky Qashat recalled a crush of students using the same exit to flee.

“It was like a herd of animals running down the stairs. I remember there was one girl that fell down the stairs because there was so much pushing and shoving,” she said.

“Then we stood outside trying to figure out what was going on.”

Until that afternoon, Everett was best known as the school that produced college and future NBA star Earvin “Magic” Johnson, who had graduated a year earlier.

The shootings bestowed a new, unwanted notoriety.

Following Needham’s arrest, police searched the teen’s bedroom, where they discovered a cache of Nazi literature, Nazi armbands, a Nazi flag and excerpts from “Mein Kampf.”They found an elaborate drawing of a concentration camp, complete with gas chambers, along with a diary Needham called “My Struggle,” named after Hitler’s book.

In one of the entries, Needham wrote: “I almost abandoned Hitler last night ─ out of being pushed too far by my colleagues. I almost went to school without my Nazi pin in my jacket. But luckily again I had a burst of courage and never again will I think about abandoning Mein Fuhrer and Nazism.”

The entry was written two days before he shot Draher and Jones.

Different time, different approach

The shooting rampage at Oxford High School happened on a Tuesday.

That Thursday, two days later, Oakland County Prosecutor Karen McDonald announced that the suspect, 15-year-old Ethan Crumbley, who was found to have left disturbing, blood-filled drawings of shootings on his desk at school the morning of the shootings, would be charged as an adult.

He now faces more than 20 felonies, including a terrorism charge and four counts of first-degree murder. If convicted, he could face life in prison.

That was not the legal route taken by the young shooter in 1978. After evidence was submitted that Needham had considerable mental-health issues, his case was handled in juvenile court.

According to the Tampa Bay Times account, a psychiatrist retained by the prosecution determined Needham was a “true paranoiac.”

An assistant prosecutor was quoted by the Associated Press as saying he was not optimistic Needham could be rehabilitated.

“He’s a terribly dangerous person whose only disappointment is that he didn’t kill more people when he had the chance. He feels no remorse,” the prosecutor argued.

But in October 1978, Lansing probate judge Donald Owens ordered Needham to undergo psychiatric treatment, sentencing him to a juvenile detention facility, the W.J. Maxey Boys Training School north of Ann Arbor. He began seeing a psychiatrist several hours a week.

Under Michigan law governing juvenile justice at the time, Neeham could be held only until age 19 unless he still proved to be a danger to the public.

But then something surprising happened.

Needham, considered a brilliant but angry student before the shootings, quietly applied himself during his detention at W.J. Maxey. He earned a high school degree in 1979. He took up tutoring other juvenile inmates and showed a particular talent for math, according to the Tampa Bay account.

Under supervision, he began taking classes at the University of Michigan. With prison staff convinced Needham no longer posed a risk to others, he was set free less than four years after he shot and killed Bill Draher.

In August 1984, Needham received a bachelor’s degree in science from U-M with “highest distinction.” Four months later, he received a master’s degree in mathematics and, in 1992, a PhD in mathematics from U-M, according to the Tampa Bay account.

U-M mathematics professor Robert Griess, Jr. was among four professors assigned to advise Needham. He told Bridge that he recalled a long-haired student stepping into his office nearly 30 years ago to talk over his doctoral thesis.

“He answered all my questions,” Griess said.

“I remember him as a very pleasant, shy fellow. He just sort of blended into the atmosphere of the department.”

Griess said he had “absolutely no idea,” until informed by Bridge, that Needham had killed a high school student 14 years before they met.

A few years after finishing at U-M, Needham was hired as a visiting professor in mathematics at City College of New York, where he worked on a research project funded by the National Science Foundation that fused mathematics and computer science. Colleagues at CCNY reported that they heard that Needham had joined a computer firm, but they were unsure exactly where he went after leaving CCNY, according to the Tampa Bay report.

Bridge was unable to verify Needham’s current whereabouts or any vocational pursuits after that.

Poole, the Everett classmate, likewise told Bridge he was “shocked” to learn of Needham’s path after his release. But he said the news erases none of the pain Needham inflicted when he was 15.

Poole said he had a close friend group in high school that included Draher as well as Jones, the boy grazed by the first bullet. Poole slept at Draher’s house several times, and the pair took in a few movies and made trips to a local bookstore to check out the latest Marvel comics.

“He and Kevin and I, we all liked to play around,” Poole said. “Everything was to have fun.”

After the shooting, when he learned Bill was killed, “it hurt, and it also made me mad.”

All these years later, Poole hasn’t completely moved on. There’s a part of him that remains angry at Needham.

“In his time on earth, he removed somebody from this earth with his gun,” Pool said. “Just because he became a better person now, it doesn’t change the fact that he killed somebody and he only served four years for it.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Health Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!