Is state losing its love of fish?

Longtime fly fisherman Robert Thorsen enjoys solitary fishing experiences, but the suburban Detroit resident fears he and other anglers may be enjoying too much of a good thing.

“I see a lot of stretches of rivers that are deserted,” Thorsen said. “As a fisherman, I don’t mind if there are fewer people on the water because that gives me more space.”

As a conservationist, however, Thorsen is concerned.

“If fewer people are buying fishing licenses, that means there is less money for the state’s Fish and Game Fund,” said Thorsen, a life member of Trout Unlimited who owns a cabin on the upper Manistee River.

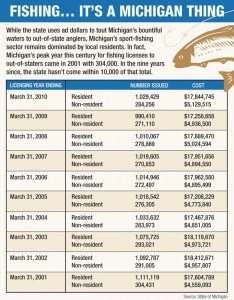

The number of licensed anglers in Michigan has dropped by 20 percent since 1995, and continues to decrease at a rate of 1 percent to 2 percent annually, according to state officials.

Fewer anglers mean less money for the Fish and Game Fund, which translates into less funding for programs that nurture and protect Michigan’s myriad of fisheries and wildlife populations.

That trend is particularly alarming because Michigan’s fisheries program, which generated $1.6 billion of economic activity in 2006 (the most recent statistic available), is funded almost entirely with revenue from the sale of fishing and hunting licenses.

“We’re not seeing a decline in fishing because the fisheries suck -- our fisheries are as good as they’ve been in decades,” said Jim Dexter, acting chief of fisheries for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

Michigan has one of the nation’s largest and most diverse fisheries. The state borders four of the five Great Lakes, has more than 10,000 inland lakes and 36,000 miles of river and streams -- 12,500 miles of which are coldwater trout streams.

Field & Stream magazine recently named Michigan the nation’s best state for fly-fishing.

Yet, the ranks of anglers fishing here continue to slide.

A study released this year of the charter fishing business in the Great Lakes found significant declines in charters from out-of-state visitors and from the Flint and Detroit areas between 1990 and 2009. The charter business, concentrated heavily in Lake Michigan, has averaged a $20 million annual economic impact for coastal communities in the last two decades.

“This is one of the state’s most interesting conundrums,” Dexter said. “We have so many fantastic fishing opportunities and our inland fisheries are second to none, and yet we continue to see this decline in the number of anglers.”

Money hole fished out?

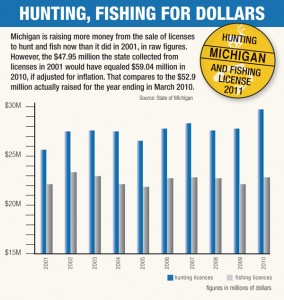

Revenue from fishing license sales in Michigan increased by 5 percent between 2001 and 2010. But that increase lagged far behind the rate of inflation, which jumped 27 percent over the past decade.

The fisheries division budget has been cut 10 percent over the past five years, and the number of full-time employees has been slashed by 25 percent since 1990. Dexter said revenue from license sales is not keeping pace with rising employee expenses and the increasing cost of maintaining fish hatcheries, research boats and other essential equipment.

The fisheries division budget has been cut 10 percent over the past five years, and the number of full-time employees has been slashed by 25 percent since 1990. Dexter said revenue from license sales is not keeping pace with rising employee expenses and the increasing cost of maintaining fish hatcheries, research boats and other essential equipment.

The DNR has a backlog of more than $1 million in maintenance work at hatcheries and fish ladders. Three of the agency’s four research vessels, which monitor the health of Great Lakes fisheries, are more than 40 years old.

The most obvious solution to Michigan’s steady decline in funding for fish and game programs would be to raise the price of hunting and fishing licenses. Michigan’s license fees are among the most inexpensive in the nation, according to DNR officials.

But several DNR officials and conservation leaders interviewed for this article said that isn’t likely to happen because the state’s struggling economy has created a climate that is hostile to tax boosts or fee increases of any kind.

An annual, all-species fishing license for a Michigan resident is $28, far less than the price of admission to a Detroit Lions, University of Michigan or Michigan State University football game. A deer-hunting license for state residents costs about as much as a 12-pack of beer: $15.

Michigan hasn’t raised fees for fishing or hunting licenses in several years. An attempt to win public support for a fee increase was derailed back in 2007 when DNR officials discovered $10 million in the Fish and Game Fund that had not been accounted for.

Several DNR officials and conservation leaders saidMichiganshould adopt an entirely different funding mechanism for fish and wildlife programs, one that is similar to those in Missouri and Minnesota. Those states recently allocated a portion of state sales tax revenue for fish and game programs, which dramatically increased funding in those areas.

“Minnesota has about 200 more employees in its fisheries program than we do,” Dexter said.

Wanted: young anglers

Without an immediate solution to the funding crisis for fish and wildlife programs, the DNR and several conservation groups have stepped up efforts to recruit a new generation of conservation-minded hunters and anglers. But that can be a tough sell in a digital world, where kids can partake in virtual hunting and fishing trips via video games.

Thorsen, the fly fisherman from suburban Detroit, has made introducing children to nature a personal crusade. He volunteers as a Cub Scout leader at his 8-year-old son’s school and makes a point to take his young charges outdoors as often as possible.

“When I take my Cub Scouts into nature, they have a blast,” Thorsen said. “The best thing we in the conservation community can do is provide opportunities for kids to experience the outdoors.”

Thorsen practices what he preaches. There is no television or computer at his family’s cabin along the Manistee River. “We just go outside and play, or we go fishing,” Thorsen said.

Jory Dirkse, a 31-year-old fishing guide on the Pere Marquette and Muskegon rivers, said his parents instilled in him a passion for fishing and spending time outdoors.

Jory Dirkse, a 31-year-old fishing guide on the Pere Marquette and Muskegon rivers, said his parents instilled in him a passion for fishing and spending time outdoors.

“When I was young I loved going outdoors,” said Dirkse, who grew up in Holland.

Dirkse said his father taught him how to fish and his family often traveled to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He said positive experiences with his friends and family made him want to spend as much time a possible outdoors. Now he makes a living taking other fishing on some of Michigan’s best rivers. “It’s not the most lucrative job but it pays the bills and I love being out on the river.”

Dirkse said he believes the keys to cultivating a passion for the natural world in kids are “parents and opportunity.”

“The main thing is just getting kids outdoors, whether it’s to go fishing, bird watching, or hunting for morel mushrooms,” he said. “Just pick something that’s in season and do it.”

Tom Heritier, president of the Saginaw Field and Stream Club, said he fears that legions of children raised on Facebook, Twitter and video games will never experience the beauty of fishing at sunrise, the joy of seeing an eagle soar, or learn the intrinsic value of clean air, clean water and healthy fish and wildlife populations.

“If they have no exposure to nature, they have no idea what they need to conserve,” Heritier said. “We are supposed to be stewards of our environment but if somebody doesn’t have a clue about how nature works, they won’t do anything to protect it.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!