Up or down? Which way are Great Lakes water levels headed?

In January, when Lake Michigan’s chronically low water level reached its nadir, Leland Harbormaster Russell Dzuba faced the prospect of closing the popular harbor to keep commercial fishing vessels and pleasure boats from running aground in the shallow channel.

Leland is one of dozens of Great Lakes harbors that have struggled for two decades with below average lake levels that damaged boats and caused freighters to carry less cargo to avoid hitting bottom. Closing Leland’s harbor would have been devastating, Dzuba said.

“Our economy lives and dies on whether that channel (to Lake Michigan) is open,” he said.

The lake level crisis abated in April, when torrential rains caused lake levels to rise at an almost unprecedented rate.

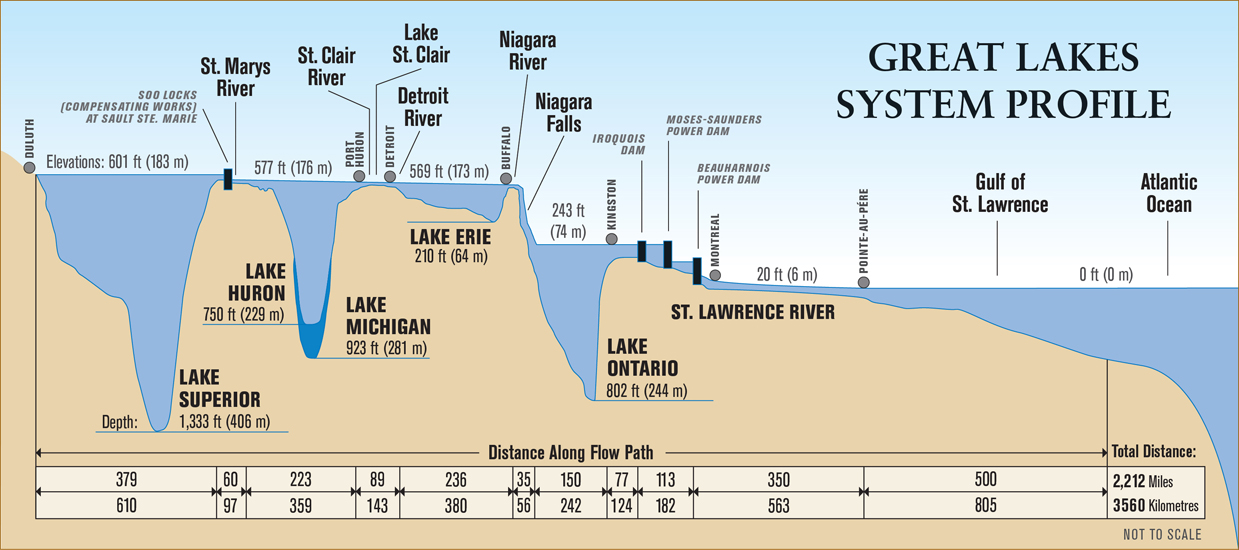

From April through August, storms and the resulting stormwater runoff pumped 11 trillion gallons of water into Lake Superior. Another 16 trillion gallons ran into lakes Michigan and Huron (technically one lake) — which is equivalent to the flow of Niagara Falls over the course of 247 days.

The deluge caused water levels in lakes Michigan, Huron and Superior to rise 20 inches — nearly double the average spring rise in lake levels, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Given that sudden, phenomenal rise in water levels, it would be understandable for lake observers to assume that Great Lakes water levels are back to normal, that all is well.

But not so fast.

Climate change and manmade alterations to the lakes have caused significant changes in the Great Lakes.

Lake Superior has largely recovered from low water levels that nearly set a record in 2007. But water levels in Lake Michigan-Huron remain 18 inches below their long-term average, largely because dredging in the St. Clair River prior to 1970 created a larger drain for that lake.

By the end of the year, Superior’s water level is expected to reach its long-term annual average for the first time in a decade, said Keith Kompoltowicz, chief of Great Lakes watershed hydrology at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Detroit office.

Without another flood or above-average snowpack in the upper Great Lakes, water levels in Lake Michigan-Huron won’t return to their long-term average anytime soon, Kompoltowicz said.

“It would take a prolonged period of very wet conditions to get us back to the long-term average on Lake Michigan-Huron,” he said.

Which way will lake levels sway?

Most studies of future lake levels have concluded that climate change will cause lower lake levels in the future. But others predict lake levels will rise as climate change increases precipitation in the basin.

“It’s hard to predict lake levels in the future,” said Drew Gronewold, a hydrologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory in Ann Arbor. “The lakes could go up or they could go down — that’s entirely true.”

Despite that uncertainty, Gronewold and other scientists said there are reasons to be concerned about the future. Consider:

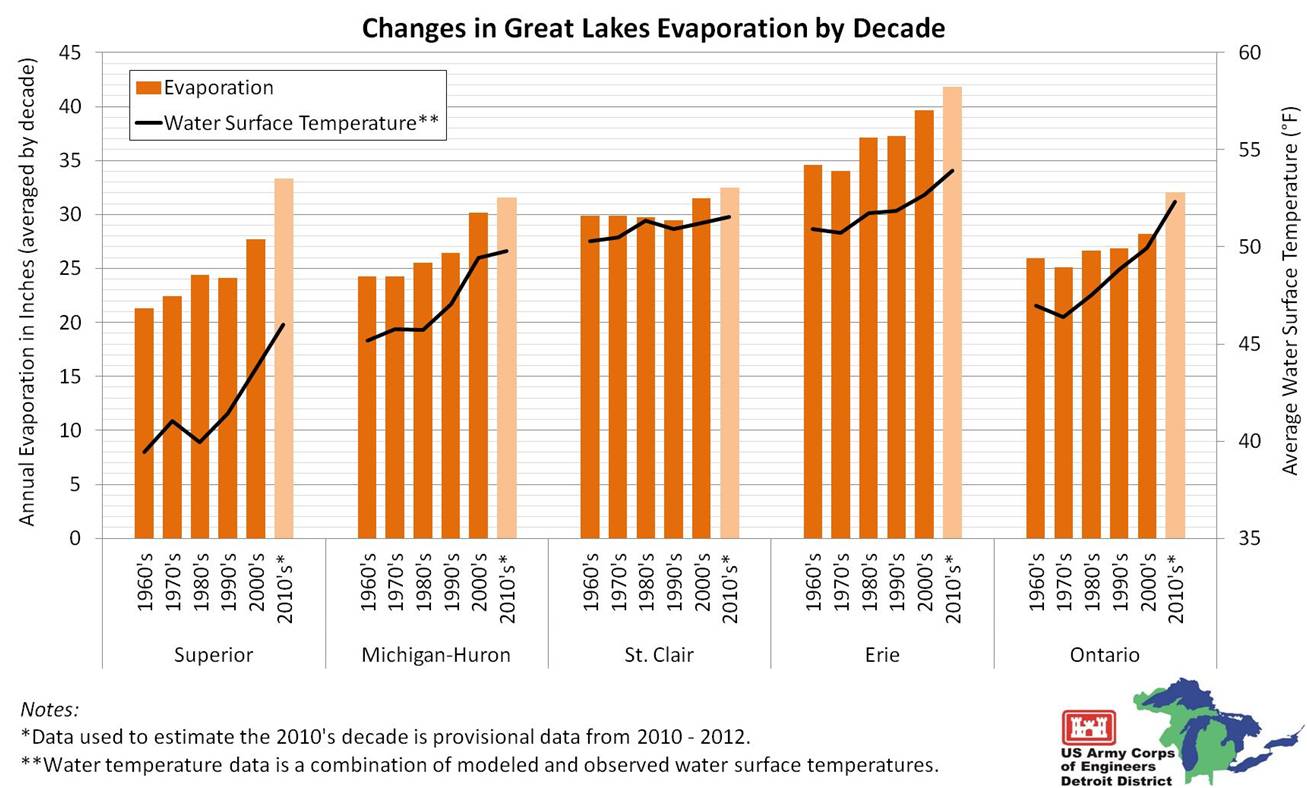

• Great Lakes ice cover has decreased 71 percent over the past 40 years. Less ice contributes to warmer water temperatures and increased evaporation —the single largest source of water loss in the lakes.

• Great Lakes water temperatures are rising, according to government data. Average summer water temperatures in the normally frigid Lake Superior, the world’s largest lake by volume, have increased 4 degrees since the 1980s. Superior is now one of the fastest-warming lakes on the planet, according to research by scientists at the University of Minnesota-Duluth.

• Evaporation has increased dramatically over the past 50 years, according to Army Corps of Engineers data. Evaporation has more than doubled in Lake Superior since the 1960s and has increased 44 percent in Lake Michigan-Huron, 45 percent in Lake Ontario and 17 percent in Lake Erie.

• Most climate change models predict a continued increase in Great Lakes water temperatures, even less ice cover and more evaporation from the lakes. Climate change is also causing more extreme storms, which causes flooding that flushes more pollutants into the lakes.

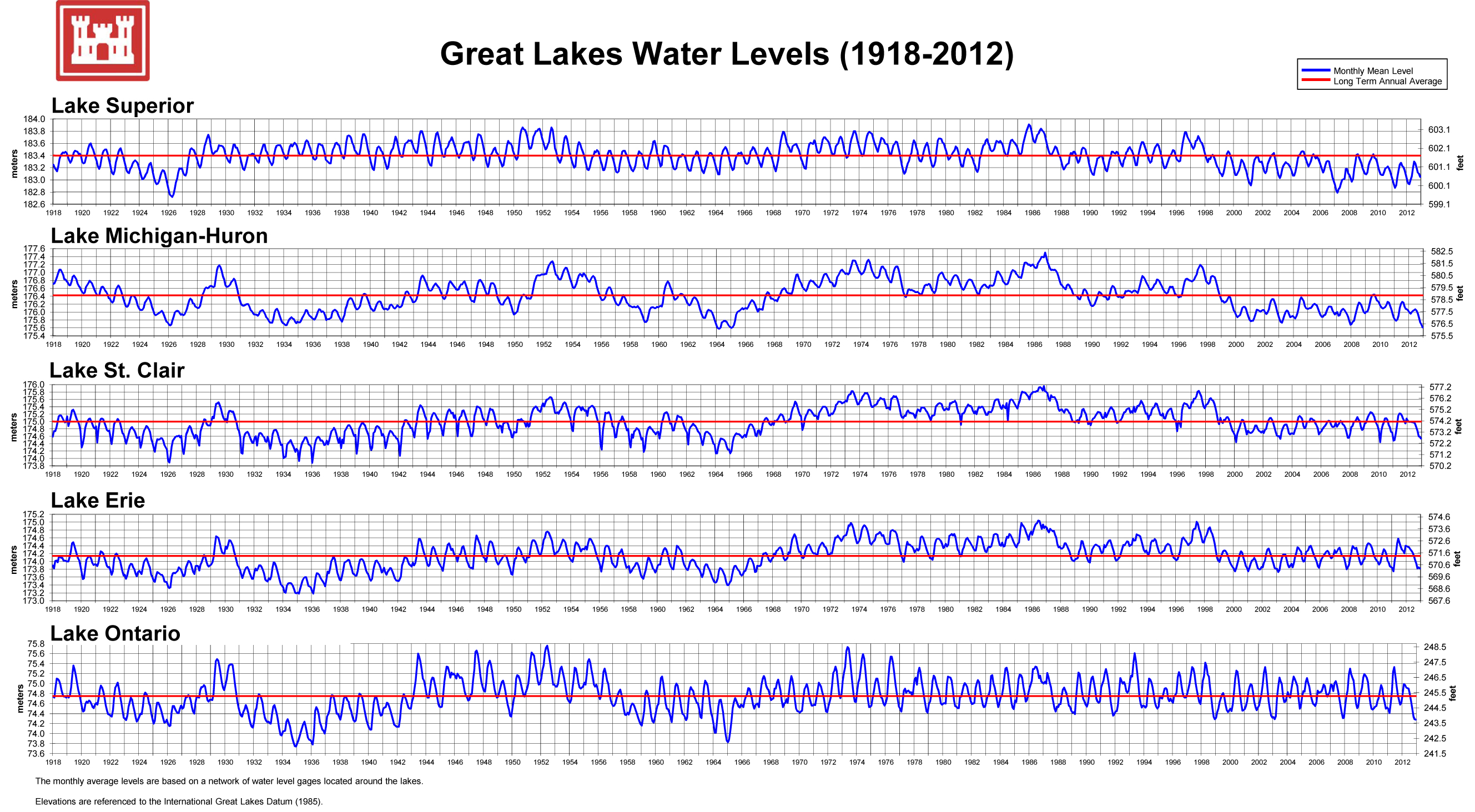

Great Lakes water levels fluctuate seasonally and over longer periods of time, but those levels have remained within a range of 6.5 feet over the past 150 years, according to government data. They remained within that 6.5-foot range even during periods of high water in the 1980s and the record low lake levels recorded earlier this year.

El Niño years ago still having an impact

Gronewold said researchers believe an El Niño event in 1997-98 — a prolonged warming of Pacific Ocean temperatures that caused catastrophic weather changes around the world — was responsible for a cascading series of events in the Great Lakes. The El Niño event, coupled with a long-term rise in air temperatures in the Great Lakes region, caused warmer water temperatures, less ice cover, increased evaporation and ultimately, sinking lake levels.

Levels plummeted in all of the Great Lakes except Lake Ontario between 1997 to 2000, and dropped nearly three feet in Lake Michigan-Huron, according to government data. Lake levels in Superior, Michigan and Huron didn’t recover until this year.

“That 1997 event provided a pretty significant shock to the (Great Lakes) system,” Gronewold said. “That drop in lake levels set the stage for the recent all time lows that we just experienced.”

The looming question is whether the low lake levels that dominated Lake Michigan-Huron for nearly two decades will be the new normal in the future.

Don Uzarski, director of Central Michigan University’s Institute for Great Lakes Research, believes climate change will cause lake levels to trend lower in the future.

“We’re breaking weather records every year and the lakes are going to continue to fluctuate due to that, but they are going to fluctuate in a downward trend,” Uzarski said. “I believe majority of scientists would predict lower water levels.”

Winners and losers in low lake levels

Persistent low water levels in lakes Michigan and Huron from 1997 through March 2013 were a boon for lakefront property owners along the Lake Michigan coast, who enjoyed unusually large beaches. But they were a nightmare for the shipping industry, boat and marina owners, and property owners in Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay. Ships were forced to carry less cargo to avoid running aground, marinas spent heavily on dredging activities, and property owners on Georgian Bay saw Lake Huron’s water lake recede as never before — leaving some islands high and dry.

The shipping industry and marina owners have repeatedly called for more government-funded dredging in shallow Great Lakes harbors. Property owners on Georgian Bay have lobbied for the installation of structures on the bottom of the St. Clair River that would counter the effects of dredging and cause water levels to rise in lakes Michigan and Huron.

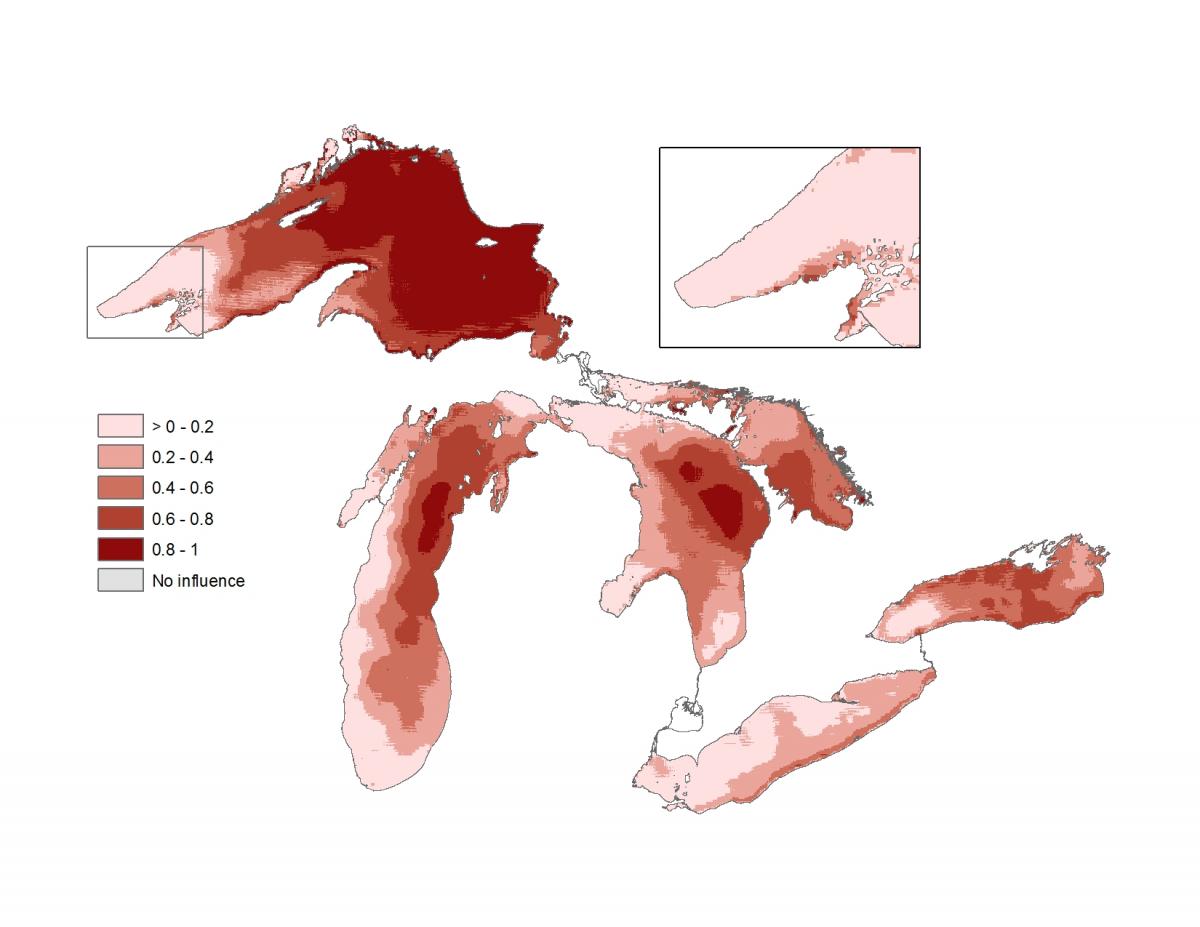

A study by the International Joint Commission — a U.S.-Canada agency that monitors Great Lakes issues — concluded that dredging and other human activities in the St. Clair River prior to 1960 lowered water levels in lakes Michigan and Huron by 14-16 inches. Additional dredging of the river in 1962 caused lake levels to drop another 5-inches, IJC spokesman John Nevin said.

Researchers also found that glacial isostatic adjustment, a post-glacial rebounding of the Earth’s crust that is causing lakes Michigan and Huron to slowly tilt toward Chicago, has caused a roughly 2-inch drop in lake levels in Georgian Bay over the past 50 years.

The IJC recently recommended studying the feasibility of building flow-regulating structures in the St. Clair River, which could raise water levels in Lake Michigan-Huron by 5-to-10 inches.

Nevin said the IJC’s goal is to elevate water levels in both lakes without causing flooding or other shoreline property damage.

But the notion of exerting more human control over Great Lakes water levels is controversial.

Lana Pollack, a former Michigan state senator who is now co-chair of the IJC, was the only IJC commissioner to oppose studying the possible placement of structures in the St. Clair River. She said blaming low lake levels solely on dredging that opened a larger drain hole in the river is oversimplifying a complex problem.

“We can no more blame dredging for low water than we can say that children fail to learn to read because they lack glasses or healthy breakfasts,” Pollack said in a recent essay in a Canadian newspaper. “No doubt, some of them need glasses and better breakfasts, but many other factors are involved.”

A number of scientists and conservation groups claim fluctuating lake levels are normal and healthy for the lakes’ ecosystems, particularly coastal wetlands.

“While these lake levels are bad for shipping and recreational boating, they are good for coastal wetlands,” said Uzarski said.

Human activities have already eliminated half of all Great Lakes coastal wetlands, which are havens for wildlife and aquatic life.

Uzarski said imposing more human control over lake levels would open a can of worms. Still, he understands why some people are adamant that lake level control structures be built in the St. Clair River.

“When I’m out on my boat and my prop hits a rock, I want higher lake levels, too,” he said.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge