Workers weary, patients angry, as COVID fills Michigan hospitals — again

With an eye on his father’s bloodied face, Barry Jensen began punching numbers into his cell phone from the hospital emergency room.

His 90-year-old dad had fallen on a gravel driveway. His glasses were broken. His family worried that his bones might be, too.

Related:

- Beaumont Health sets up triage tents outside some hospitals to manage COVID-19 surge

- Demand for vaccine declines in parts of Michigan, even as COVID surges

- Michigan at 'record high' for COVID-19 hospitalizations of children

- No new restrictions, but Michigan needs help amid COVID surge, Whitmer says

- University of Michigan postpones surgical procedures because of COVID-19 surge

Stories from the front

Bridge Magazine, Detroit Free Press and Michigan Radio are teaming up to report on Michigan hospitals during the coronavirus pandemic. We will be sharing accounts of the challenges doctors, nurses and other hospital personnel face as they work to treat patients and save lives. If you work in a Michigan hospital, we would love to hear from you. You can contact reporters Robin Erb rerb@bridgemi.com at Bridge, Kristen Jordan Shamus kshamus@freepress.com at the Free Press and Kate Wells katwells@umich.edu at Michigan Radio.

Seats inside the Beaumont Hospital emergency room in the downriver Detroit community of Trenton were filled that day in late March. Several people lay on gurneys.

The son remembers thinking “it looked like a scene from a disaster movie, just on a smaller scale.”

A doctor might be free to see his father in another three, four, maybe even five hours, Jensen was told.

And don’t bother trying Henry Ford’s Health Center in Brownstown or its Wyandotte hospital, the hospital staffer warned — they were just as busy. As Barry Jensen listened, his wife used a water bottle and some antiseptic foam to dab her father-in-law’s face.

Similar scenes have been unfolding in emergency rooms across Michigan these days amid a steep rise in COVID-19 cases.

By Friday — even as the state administered its 5 millionth vaccine — some hospitals had returned to banning visitors, halting non-emergency procedures and implementing pandemic surge plans.

Nearly two dozen hospitals had reached 90 percent capacity, according to data compiled by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. More than 15 percent of Michigan hospital beds held COVID patients.

Six metro Detroit counties were reporting the most patients since the pandemic’s first, terrifying wave last spring. That meant there are fewer hospital beds available now then when 90-year-old Dean Jensen waited for hours in Trenton. (His family was able to get him treated at the Detroit Medical Center, where he received 18 stitches.)

Tina Freese Decker, CEO of Grand Rapids-based Spectrum Health, joined Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and Dr. Joneigh Khaldun, the state’s chief medical executive, urged Michigan residents Friday to stay masked up and follow social distancing protocols.

The state was investigating 991 outbreaks and “broad community spread,” Khaldun said. It has been a week of horrid numbers, with Michigan leading the nation in new infections, hospitalizations and the percentage of people testing positive for COVID.

“What's concerning,” Spectrum Chief Operating Officer Brian Brasser said in an interview, is “that our trajectory looks very, very similar to what it did in the first part of October.”

Which is why Spectrum was among those canceling some procedures.

“Any time we make a decision to defer procedures like this, it comes not lightly because we recognize that the risk that is associated with deferred care,” Brasser told the Free Press. “But we also need to make sure that we're providing good, safe and effective care and we recognize that with the spike of COVID inpatient activity and just a general high census overall, it was important for us to do that.”

Other health systems made the same choice including Michigan Medicine, Henry Ford Health System’s Macomb County hospital in Clinton Township, and Mercy Health Muskegon Medical Center.

If case rates continue to climb, leaders at Beaumont Health, McLaren Health Care, Ascension Michigan and Sparrow said they will consider similar measures.

Meanwhile, public health officials, including those charged with contact tracing and other health efforts, are struggling to keep up, too.

“Our public health system is overwhelmed, we cannot keep up the pace, with all of our new cases that are coming in every day,” Khaldun said.

On the inside

It is a dreaded deja vu, with a few notable differences, several health care workers told Bridge Michigan and the Detroit Free Press in recent days.

Gone is the fear of the unknown when the coronavirus first hit last spring and the frantic scramble for personal protective equipment.

But gone, too, are the stream of community-provided meals and well wishes that buoyed frontline workers in those early days.

And the camaraderie forged in the early chaotic days has started to crack in places, not necessarily in front of patients, but behind the scenes.

“There’s bickering amongst each other because they’re stressed out,” said Josephine Walker, a nurse at Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital, and a vice president of the nurses union, OPEIU Local 40.

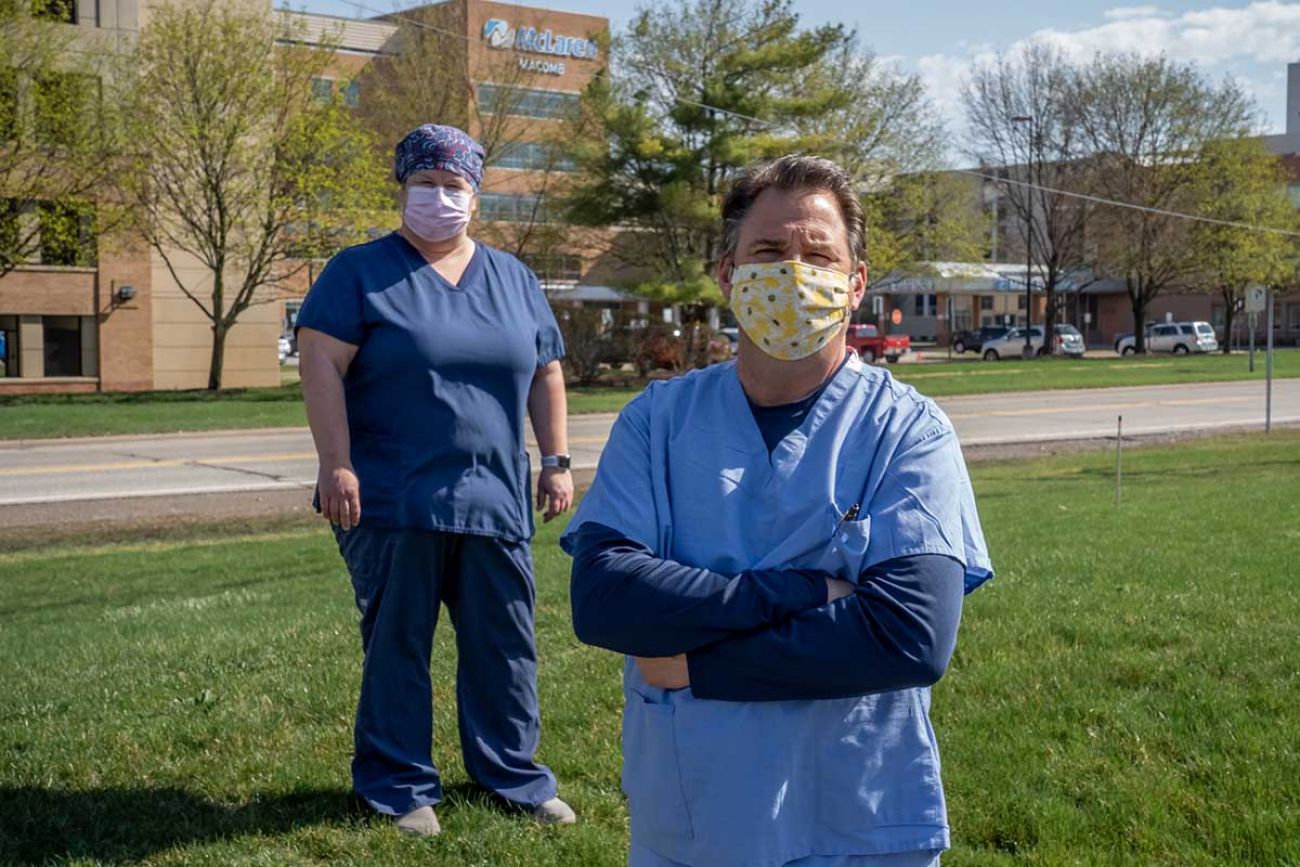

It’s a familiar, bone-deep weariness as staff moves from patient to patient, said Jeff Morawski, a long-time nurse and president of the OPEIU Local 40, which represents nurses at McLaren Macomb Hospital in Mount Clemens as well as the Ascension site.

“There are cases, there are surgeries, there are procedures. The ERs are filled,” said “We are busting at the seams.”

And that inevitably means it’s patients who wait. And wait.

Colleen Rowland said she waited for seven hours Tuesday in a packed emergency room at Beaumont Hospital, Taylor — in pain from kidney stones and a raging urinary tract infection.

“It just didn’t seem like I was in the U.S. anymore,” said Rowland, 25, a respite care worker.

She said she arrived mid-morning at the emergency room after pulling to the side of the road in sudden pain and vomiting en route to her job. She was told at an urgent care facility she needed hospital care.

“You get used to being privileged, to not being in pain,” Rowland said. But “everybody in that room was miserable. There were people just keeled over in their seats over puke buckets.”

Rowland said she wasn’t able to get a hospital room until after dinner Tuesday, then had surgery Wednesday.

McLaren’s Chief Medical Officer Dr. Michael McKenna said the system’s hospitals are “definitely packed” both with COVID patients and others unlucky enough to require hospital care in a pandemic.

“When we're at full capacity, … we have had to temporarily hold people, like in the emergency room, but typically we're able to get them up to the floor” as other patients are discharged and free up beds, he said.

At Trinity Health’s eight Michigan hospitals — which include the St. Joseph Mercy and Mercy Health systems — 90 patients were in emergency rooms waiting for open beds Thursday morning, said Rosalie Tocco-Bradley, its chief clinical officer.

“Everybody is really tight right now,” she said.

The worst night

For intensive-care unit nurse Kim Stasik, 38, who works at Beaumont Hospital in Trenton, Monday was “hands down” the worst night in her 15 years in the profession.

“These people are sick,” she said. “They're young. They require a lot of care.”

In the hospital’s intensive care, there is usually one patient for every nurse. When it’s busy, that can sometimes bump up to two patients per nurse. On Monday night, the ratio was 3-to-1.

“We are tired now," Stasik said. "People aren't picking up those extra shifts. The (pay) incentives that they are giving ... are just not worth it anymore. Yes, you can make that extra money, but at what cost?

“It's hard. People are just emotionally exhausted.”

Morawski, the McLaren nurse, agreed. The extra $20 to $50 an hour for some shifts is no longer worth it.

“People want to see their families again, they want to be home,” he said.

Stasik said her emergency department has been at capacity for three weeks straight.

“Every unit was full. Every unit had every bed full, including our ICU.

“We had nowhere to go. We had nowhere to put people.

“We've had patients as young as 22,” Stasik said. “A lot of the people we’re treating are friends and family members of people we know.”

The Whitmer administration and others have noted that, despite the rise in cases, death rates have dropped among people who contract COVID-19, likely because patients tend to be younger than before vaccines became available, and hospitals have had a year to learn how to better treat the virus.

Then again, such conclusions may be premature. Deaths usually are a lagging indicator. Coronavirus spikes around the world have followed the same pattern since the start of the pandemic: infections first, followed by hospitalizations, and then deaths.

For frontliners like Stasik, the unknowns remain frustrating.

“Nothing correlates, and nothing makes any medical sense,” she said.

One year later, less support

Hospital workers interviewed this week said that, in addition to an ebb in community support during the pandemic, they face an added squeeze these days as they treat COVID patients.

When hospitals canceled nonemergency procedures last spring, nurses and other staffers who worked in heart labs or with orthopedic patients were redeployed to help on COVID floors. They would serve as “runners” for their colleagues in patient rooms — fetching medications, supplies or more protective equipment when needed.

Now, staffers in non-emergency departments largely remain in their regular posts, despite the latest surge.

“The last couple of weeks it has been insane,” said Terri Dagg-Barr, another McLaren Macomb nurse.

Meanwhile, younger COVID patients are more likely to wait until the last minute to come to the hospital, rather than getting in touch with their primary care physician when they first feel sick or test positive, she and others said.

“I used to love my job,” Dagg-Barr said. “But right now it’s so frustrating.”

Why they return for another shift

Fresh out of nursing school, Miranda Macko, 25, walked into Beaumont Trenton in January, thrilled to be able to make a dent — she thought — in the pandemic.

The 12-hour days standing at bedsides and computers, she expected. She knew to invest in a good pair of Brooks shoes.

But the constant turnover of patients this month has been unexpected and exhausting. Medical care is more than charts and pills. A good nurse takes time to hear patient concerns, to understand their pain, and to tend to their anxiety, she said.

It’s difficult when there is so little time, she said.

“Once we clear a room and get that room disinfected, the room is filled again,” Macko said. “We have patients coming into our ER and waiting for hours.” “I just wish people would mask up. This isn’t over.”

Even so, Macko and others said they remain thrilled to show up each shift, and thrilled even more when a patient becomes a survivor.

And, there are still notes, calls and texts from those they have helped, said Robin Cannon, clinical nurse manager for Memorial Healthcare’s COVID unit in Owosso, west of Flint.

Sometimes, the messages come directly to her cell phone — calls from grateful survivors or loved ones.

“To hear that feedback,” Cannon said, “to know they're recognizing what an excellent job that’s happening, and just being able to care for the patients — that's what makes weary worth it.”

Bridge Michigan data reporter Mike Wilkinson contributed to this report.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!