New psychiatric unit in northern Michigan to address severe care gap

- The 18-bed psychiatric unit will serve residents from 22 counties in northern Michigan

- It took more than two years to recruit a full-time psychiatrist for the center amid acute shortages of healthcare workers

- The unit will open ‘as soon as staffing is complete,’ according to a hospital spokesperson

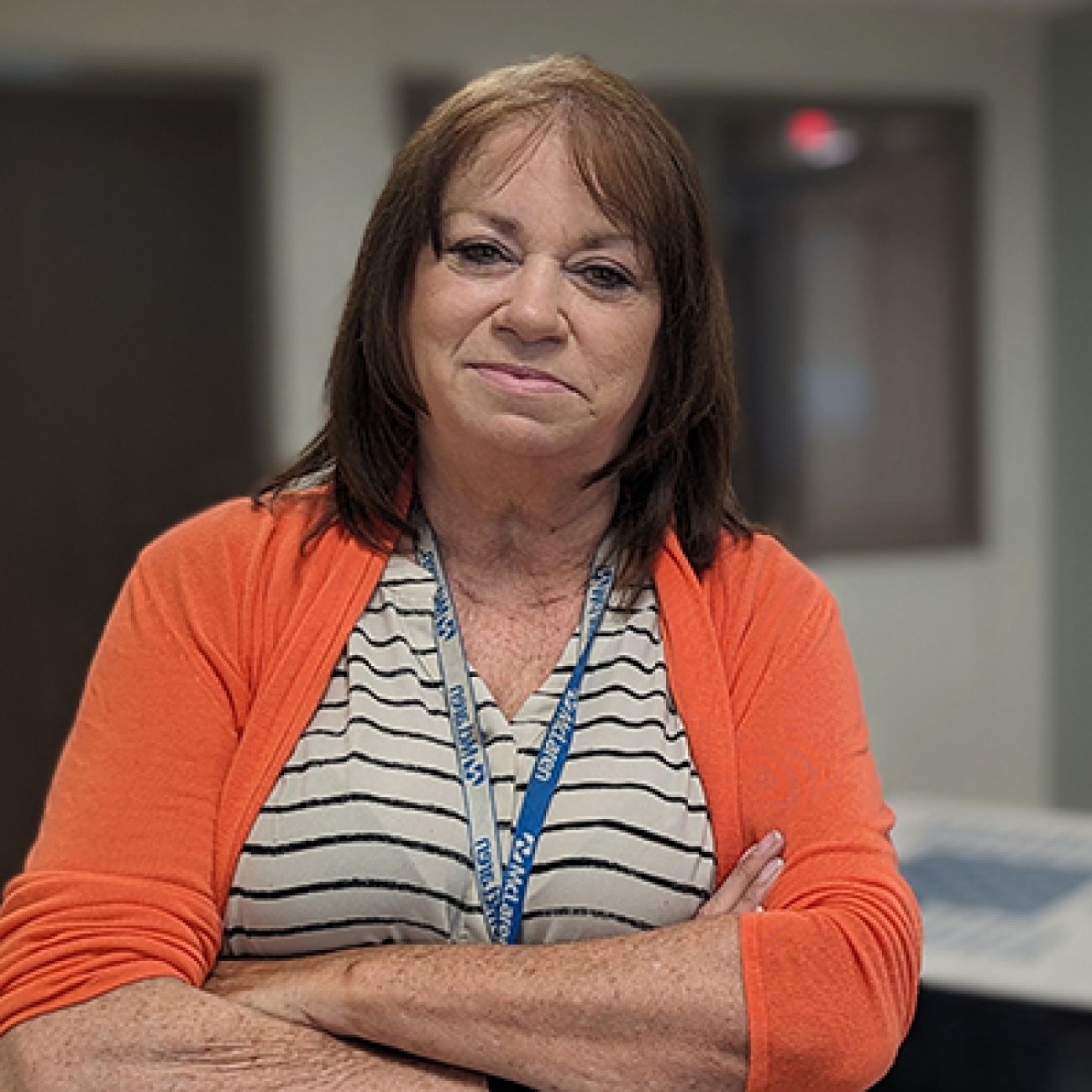

CHEBOYGAN—Decades later, Laura Daniel can still see the otherwise smooth skin of the young boy — gashed, self-mutilated — as emergency room staff ripped off his clothes to save him from a drug overdose.

The self-inflicted cuts along his arms and on his groin were likely the tell-tale signs of emotional distress of a boy — age 10 to 12, she estimates — that she’d later learn had been sexually abused for years by a family member.

Related:

- As child mental health rates rise, Michigan sharply cuts residential beds

- Mental health crisis: Children at breaking point during COVID

- Michigan bill intended to shorten ER waits for youth in mental health crisis

As a young intensive care nurse, Daniel remembered the grim revelation that day: Even after they saved the child from the drug overdose, she knew his mental health problems would be too big for even the best emergency room team to handle. And further: where would he go?

In Michigan, it’s been a long-standing problem that there are too few inpatient treatment beds for children and adults in mental health crises.

“It’s extremely frustrating as a nurse when there are no services available,” she said. “You feel like you’re letting the patient down, the family down.”

Now at the end of her career as a long-term McLaren Health Care nurse, Daniel has overseen the development of at least one solution to what has become a revolving door for mental health patients at many Michigan emergency rooms.

This summer, the 18-bed Pulte Family Foundation Adult Inpatient Behavioral Health Unit — a psychiatric unit within Grand Blanc-based McLaren Health Care — will serve patients from 22 northern Michigan counties, including some who would have otherwise had to drive 100 miles or more for such intensive care, Daniel said.

Michigan’s lack of long-term, residential mental health care is well documented, and hospital emergency rooms in recent years have been forced to fill a gap in care even if woefully unprepared to do so.

When it opens, the unit, with its soft blue walls and simple furnishings, will serve as a place where patients can easily transition from the emergency room. Here, they’ll have access to intensive, round-the-clock care for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder and “thought disorders,” such as schizophrenia, according to the hospital.

As it stands now, Michiganders in mental health breakdowns often land in the state’s hospital emergency rooms — brought here by family or by law enforcement. There, staff members stabilize them, mending broken bones, treating overdoses, or stitching up cuts. But with their physical injuries tended to, those patients can linger in the hospital for days or weeks with nowhere to go for behavioral health treatment.

“Every day we probably have six patients in our emergency room with mental health issues waiting for a bed, waiting for placement … every day, every single day, who are waiting for placement,” Daniel said.

For patients languishing in ERs, each crisis that goes untended builds a sense of helplessness, said Dr. Matthew McKenna, a Virginia-based psychiatrist who will lead telehealth psychiatric services at the new center.

“People (with mental illness) reach out and there's no one there. And they can suffer — and sometimes not in the most dramatic ways — but they can have years and years of suffering in a way that is not needed,” he said.

In the worst cases, mental health that goes untended drives people to lash out or to turn to substance abuse, he said: “When someone tries something and (it) doesn't work, eventually they stop trying.”

After the 18-bed unit is established, the hospital will continue to expand toward “comprehensive behavioral health care,” according to McLaren.

Eventually, staff psychiatrists will see patients in an outpatient setting in the campus’ Medical Office Building, in an effort to keep mental health problems from spiraling out of control toward the kind of crisis that leads to inpatient care.

McLaren staff also will offer an after-care program for patients discharged from the inpatient psychiatric unit, allowing them to continue their treatment at the hospital during the day, but return to their homes at night.

Additionally, the unit ultimately will expand to care for adolescents as well, Daniel said.

For his part, McKenna said, he may move to Michigan. But he said he doesn’t worry that he won’t be here in person on an everyday basis. Many patients who have suffered trauma, he has found, prefer to speak to him by video because they feel more in control.

“Seeing patients through telepsychiatry is just as effective,” he said. “I've had many folks telling me they prefer it.”

‘Severely lacking’

Granted, the 18 extra hospital beds the unit will provide is normally far from newsworthy.

But this is a stretch of Michigan with precious few behavioral health options. And when it comes to mental health services, “to say (northern Michigan) is severely lacking is putting it mildly,” said Marianne Huff, president and CEO of the Mental Health Association in Michigan, an advocacy group.

In rural areas especially, Michiganders in psychiatric crises have often lingered in emergency rooms because there are too few psychiatric beds around the state, Huff and other mental health advocates have said for years. Frustrated families have turned to social media or to news outlets to voice their discontent.

The problem has become such a crucial and sustained issue that the Michigan Health & Hospital Association earlier this year began tracking how many patients each week are waiting to be moved from hospitals to residential mental health care facilities.

As of Monday, 163 people were in hospital emergency departments or inpatient beds in 50 Michigan hospitals, awaiting a transfer to such a unit, according to the MHA dashboard.

From Cheboygan, the closest psychiatric care here, Daniel said, is Alpena, about 80 miles away.

The entire state is woefully short on mental health professionals, including psychiatrists and social workers. Just last year, Michigan shut down more than 70 in-patient beds at state-run psychiatric centers because it was unable to fill hundreds of staff openings.

According to the state’s latest bed inventory, Michigan needs 97 inpatient psychiatric beds in northern Michigan and the Upper Peninsula to meet the needs of residents north of a line that stretches roughly from the thumb diagonally through mid-Michigan toward Manistee county.

‘Safety in mind’

On a sunny June day, Daniel, who has since left her position as director of the new center, led a tour of the 11,000-square foot, renovated space.

A former med-surg unit, the space inside McLaren’s Cheboygan hospital was stripped to the bare walls and cement floors and rebuilt with the safety of the patient and staff in mind.

Blue molded furniture with rounded corners is bolted to the ground. What isn’t bolted down is too heavy to throw in anger or fear. Hooks snap off the walls or flip downward with the slightest pressure, and the swinging privacy doors — bright with a picture of a field of flowers in pink, orange and yellow hues — are light foam that snap off the walls under pressure.

A special cement caulk seals dressers to the walls to close off spaces where visitors could hide drugs or other contraband.

For those in deep crisis, an isolation room has no furniture but a simple cot and mattress and padded walls.

A nurses station offers a nearly 360 degree view of the unit.

“Everything here was done with safety in mind,” Daniel said.

McLaren received $16 million in state funding, out of a $170 million effort to increase behavioral health service and facility capacity throughout Michigan, to support the new unit.

Opening date? Unknown

McLaren began renovations in 2021, but just when the center will open is unclear.

McLaren spokesman Dave Jones said the hospital has received the necessary state approval needed to open, and the unit will open “as soon as staffing is complete.”

Jones told Bridge Michigan on Wednesday that the center only needs “two key positions,” before it can open, which will be soon. He noted that a new director has not yet been announced.

In fact, it took more than two years to recruit the psychiatrist, McKenna, Daniel told Bridge.

Part of the problem, she said, is that the dearth of local mental health services meant that there wasn’t a ready supply of trained staff for the new unit.

The struggle to find workers is not limited, of course, to Cheboygan. But a rural setting makes recruitment more difficult, said Bob Sheehan, executive director of the Community Mental Health Association of Michigan.

He and Huff cited the lack of amenities that can be found in urban living as a potential barrier to recruiting, but there is something else too: Mental health jobs in rural areas often don’t pay much. In addition, services in smaller communities have smaller patient caseloads without the “economies of scale” that larger services can provide, said Huff.

But that’s precisely the reason the McLaren unit is so needed, Sheehan said. Even the state’s bed inventory underestimates the need, he said.

From his work with families and mental health care workers around the state, Sheehan said it’s clear many of the beds hospitals list go routinely empty for lack of staff.

You can draw a rough line from Muskegon to Bay City “and if you go north of that line, there’s a lack of psychiatrists. You go further north, you can’t find (people with a master’s in social work degree) who do case management, for example,” he said, adding he is “thrilled” to hear about McLaren’s plans

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!