I hate to complain, but I haven’t had water in a year. A Detroit story.

- March 9, 2020: Detroit to offer $25 water restorations as coronavirus fears mount

- Feb. 26, 2020: Detroit says no proof water shutoffs harm health. Get real, experts say.

- Feb. 19, 2020 update: Bernie Sanders blasts Detroit shutoffs as ‘outrage,’ as city seeks more help

DETROIT— No matter how weary life becomes, Litha Akins prides herself on keeping a nice home: framed photos of better days on the mantle; ribs in the oven; freshly cleaned floors and candles for comfort.

Housework is hard, though, without running water — and Akins owns one of the roughly 9,500 homes in Detroit that city records indicate remain without water after the city disconnected them for nonpayment last year.

So every day since April, the 56-year-old with lung disease said she fills up jugs from a neighbor’s home to bathe, cook and drink, while praying regularly for relief.

“I can’t keep living like this,” Akins told Bridge Magazine last week from the living room of her house on the city’s west side. “I hate to complain, but nobody should live without water for this long. I’ve been lugging water for so long, my arms are ready to fall off.”

Akins’ plight is far from unique in a payment-collections campaign that has disconnected service to 141,000 Detroit residential accounts since it began in 2014, according to water records obtained by Bridge through the Michigan Freedom of Information Act.

Last year, shutoffs spiked to 23,473, up 44 percent from 2018 when there were 16,295. As of Jan. 15 of this year, 37 percent of those disconnected accounts still didn’t have service.

And even those whose water was reconnected had to wait nearly a month, 29 days on average, according to analysis from Bridge. Less than 1 percent of shutoffs — a total of 50 last year — were turned back on in a week or less.

The analysis comes as the Detroit City Council prepares to ask Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to declare a public health crisis emergency and stop shutoffs for needy residents, a move first reported by The Detroit News. The ACLU of Michigan made a similar request to Whitmer in January.

Detroit officials say the disconnections are necessary to enforce payment in a city where nearly a third of customers didn’t pay bills before 2014. They say disconnections have improved collections to more than 94 percent,

Gary Brown, director of the Water and Sewerage Department, said the city has expanded programs to help residents and last year reached out to 47,000 customers to avoid disconnections, while enrolling 17,000 over the past few years in repayment or assistance programs.

“DWSD is continuing to work with community leaders to address the gaps,” Brown said. “We agree that more work needs to be done.”

The city can’t afford to stop shutoffs, though, because doing so would raise bills astronomically for the working poor, Brown said.

“We must look at affordability plans that do not shift the full burden while addressing the need,” Brown said.

Although city records show 9,500 homes shut off last year still lack water, Brown said internal records indicate about more than half of those homes may be vacant or illegally receiving service.

That puts the number of occupied customer homes without water at 4,000, more than all the homes in Petoskey in northern Michigan.

Whatever the number, the fact that thousands of residents are living without running water in Detroit doesn’t surprise activists who have fought Detroit for years over the disconnections.

“The entire approach of the city toward shutoffs is based on faulty assumptions,” said Mark Fancher, an attorney for the ACLU of Michigan, which has sued unsuccessfully to stop the shutoffs.

“They presume that when someone gets their water shut off it’s because of a one-time financial problem, and once they get help, they can get back on the tap. The problem is most people can’t afford bills, period, because the bills are simply too high.”

‘People have it worse’

Detroit’s average water bill is about $75 a month or about 10 percent of Akins’ monthly income from Social Security. That doesn’t include sewage fees, which add another $27 per month to her tab even though her water is off.

The bulk of the $733 in assistance that Akins receives each month, $500, goes to repay Wayne County for back taxes on her brick duplex on Taylor Street.

Akins said she’s endured one misfortune after another since her husband, Doyle, was diagnosed with cancer a few years ago. He took care of the bills, and before he died in May 2019 the house went into tax foreclosure and the water was shut off. The bill now totals $6,300.

“I’ve been so depressed. I almost had a nervous breakdown,” said Akins, who moved to Detroit eight years ago with her husband from Texas to take care of his now-deceased mother and has no relatives in Michigan. “I wish I could just find another house and move on.”

I've been so depressed ... I wish I could just find another house and move on."

— Litha Akins, a Detroiter who lives without water

Nearly 4 in 10 Detroit residents live in poverty, and city officials point out that paying for water is typically just one of many issues they face.

Akins’ furnace broke, so she’s stayed warm this winter with space heaters, running her gas stove continuously and draping heavy blankets on windows and door frames. She bathes by heating water on a stove, carrying it to her bathtub and taking sponge baths.

Her water bill spiked because of a leak in the basement, where an inch of standing water remains.

“I’ve been going through some stuff,” Akins said. Informed of her situation by Bridge Magazine, water officials said they reached out to her Friday and her water will soon be restored. A review of city records revealed a host of issues with the account including problem with a meter.

Cases like Akins are one reason the water department is now partnering city health and human services officials, officials said.

“She’s struggling with more than water service,” Brown told Bridge.

‘Into the abyss’

The city’s relief programs mostly work to avoid shutoffs, rather than help those whose water already is disconnected. Last year, 854 homes were disconnected multiple times, according to records reviewed by Bridge.

“People are hurting. People are out there in the cold because of shutoffs,” said Regina Williams, 60, who lives on Detroit’s west side and entered into a payment plan this month to avoid a disconnection over a $2,000 bill.

More help could be on the way, Brown said.

Water officials will soon ask the suburban Great Lakes Water Authority to increase the amount of assistance to Detroit residents to $5 million from $2.4 million for the Water Residential Assistance Program, an income-based program that provides up to $1,000 per household.

It was created when Detroit leased its water system to the suburban authority during bankruptcy proceedings. The 40-year deal calls for the authority to pay Detroit $50 million per year to help repair the city’s 2,700-mile network of pipes that serves about 4 million customers.

Last year, the program helped residents avoid 897 shutoffs, according to city records. That’s 2 percent of the 44,048 accounts eligible for disconnections last year because they were 60 days behind or owed $150 or more.

City officials said 3,300 total residents are enrolled in the WRAP program, while another 14,000 households are in repayment plans.

Brown called the help “compassionate and robust.” Water activist Monica Lewis-Patrick called the programs an “abysmal failure.”

She is president and CEO of We the People of Detroit, which delivers water to those whose service is shut. Last week, a family with 16 people in one house sought help from her group because water was disconnected after a landlord didn’t pay the bill, Lewis-Patrick said.

“It’s getting to the point where we’re having to rethink the vehicles we need to transport water because the need is so great,” she said.

“It’s not like people are being reckless. They can no longer afford the increases in water… and if you are shut off, there is no pathway to restoration. We’re talking tens of thousands of people going into the abyss.”

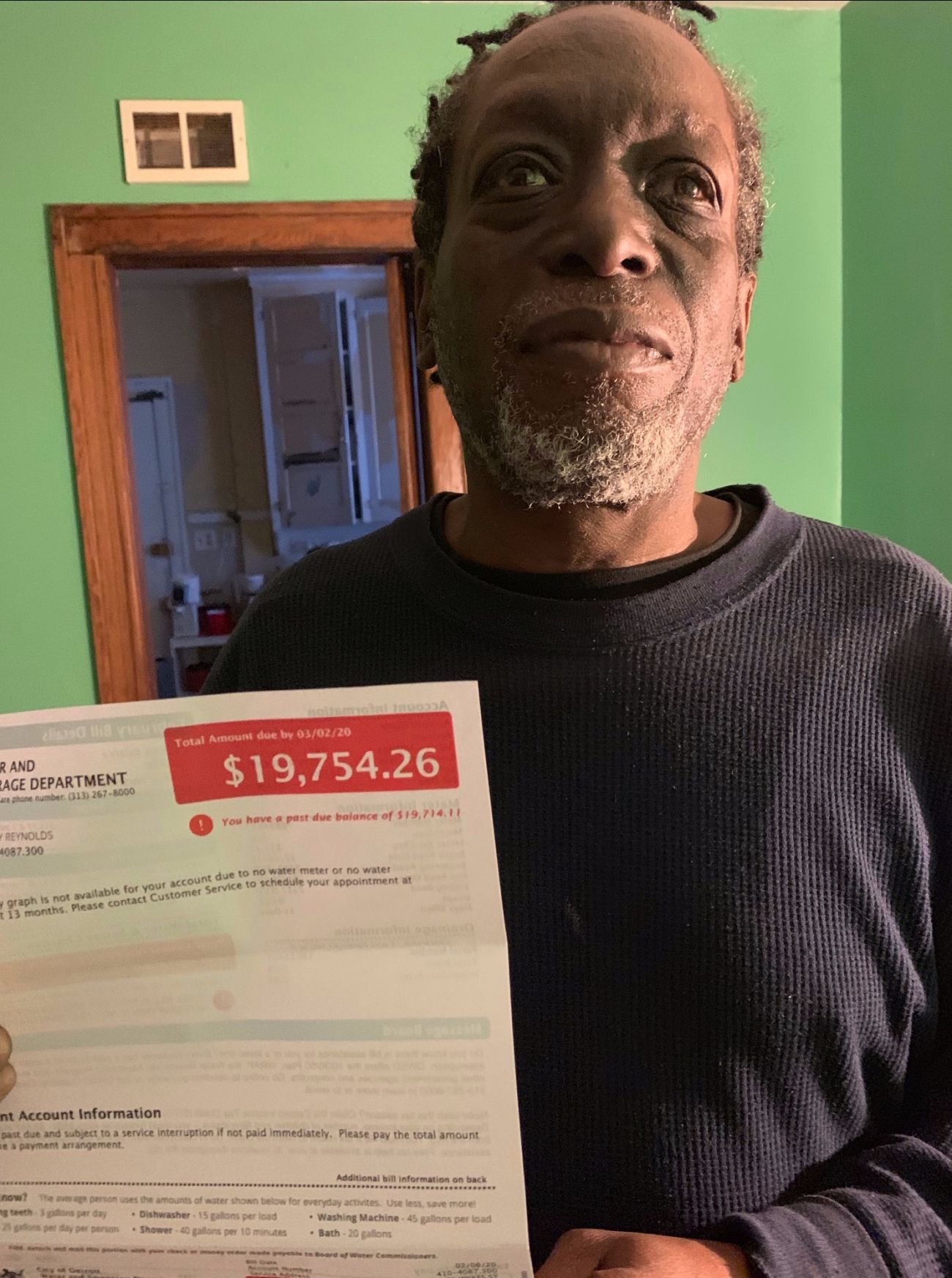

They’re people like Ricky Reynolds, who bought a home late last year for $3,000 on the city’s far west side near Dearborn.

He said he spent weeks painting, repairing drywall and restoring floors. Reynolds said he was shocked this month to receive his first water bill: nearly $20,000, presumably from a prior owner.

“How could anyone use this much water? You see this bill,” Reynolds told Bridge last week.

“I can’t pay that. Who can pay that?”

‘Shutoffs are effective’

The shutoffs are increasing as Detroit is pressed for money, trying to maintain a 100-year-old system amid declining usage.

Average daily consumption dropped 32 percent systemwide from 2000 to 2014 because of increased conservation, plumbing efficiencies and the region’s decline in manufacturing that used a lot of water, according to city documents. New state laws requiring the replacement of all lead pipes following the Flint water crisis could cost the city $500 million over the next 20 years.

Stacey Isaac Berahzer, a Georgia-based water utility consultant, said municipalities nationwide rely on shutoffs for one reason.

“They’re effective,” she said. “When there’s a threat looming over you, you pay if you can. The humanitarian side of it is different, but from a water utility perspective, they’re effective.”

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan controls the water department and supports the shutoffs, so the City Council is pleading to Whitmer who has the authority to take unilateral action if the situation is deemed a health crisis.

The council is citing an increase in water-borne illnesses, but Detroit’s Health Director Denise Fair released a statement saying the city “has found no association between service interruptions and an epidemic of any reportable communicable disease.”

A 2017 study that made that found an association between shutoffs and illnesses was so controversial that one of its own authors, a Henry Ford Global Health Initiative doctor, Marcus Zervos, disassociated himself from the findings before they were released and accused activists of twisting “preliminary findings” for “political purposes.”

“We encourage any Detroiter at risk of service interruption to contact the Water Department immediately to get connected to programs that can assist,” Fair said in her statement.

Tiffany Brown, a spokeswoman for Whitmer, said the governor doesn’t “want to speculate on a resolution that we haven’t received yet.”

Shutoffs and tradeoffs

Any pause in shutoffs likely would impact Detroit’s bottom line as it emerges from bankruptcy.

In Chicago, water collections dropped $20 million this year after a new mayor, Lori Lightfoot, ordered a halt to shutoffs, according to the Chicago Tribune.

And Detroit is far from the only city to use shutoffs for collections: Nationwide, some 15 million residents endured a shutoff in 2016, according to a report from the nonprofit Food and Water Watch.

That’s largely because water and sewer bills are increasing three times the rate of inflation each year. Michigan State University researchers in 2017 found water bills are unaffordable — more than 4.5 percent of household income — for 12 percent of all homes nationwide and will be for 36 percent of homes in five years if rates continue to rise at their current pace.

Berahzer, the water consultant, helped draft a 2018 mission statement by the American Water Works Association trade group that urges utilities to adopt affordability programs to “allow low-income households to have access to utility services.”

More communities are following suit, but the money has to come from somewhere, she said: In most cases, that means raising rates for the customers who can pay.

That was the case in Philadelphia, which in 2017 steered $18 million to a program that caps what impoverished residents pay at a portion of their income.

Since then, 20,000 residents have applied, said Robert Ballenger, an attorney for Community Legal Services of Philadelphia who helped create the program.

“This is novel for the water industry,” Ballenger told Bridge.

“It’s not novel for utilities overall, which have had regulations for years that bills should be affordable based on income. It’s just that the need for water was never as significant when the bills were $35 a quarter, as opposed to now, when they’re $75 a month.”

Ballenger called the program “an important first step,” but he acknowledged they’ve done little to quell the flood of shutoffs in Philadelphia.

The city still averages about 33,000 per year, even with the extra assistance. That’s 10,000 more a year than Detroit, a city with nearly 1 million fewer residents.

‘I have my pride’

On the west side of Detroit, Akins soldiers on. What’s the alternative, she asked on a recent day.

“I know how to survive. If people come into my house, they wouldn’t know I didn’t have water,” she said. “I have my pride.”

And her sense of humor.

Speaking to a Bridge reporter, she joked and laughed about the stress of the past year causing her to go gray and lose her good looks, and offered whatever food she had.

“I know I have it better than others because God is good,” Akins said, wiping a tear. “I don’t mean to complain. I’ve just been doing this for a long time. And it’s hard.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!