Detroit agency launches mobile mental health unit. Can it slow a revolving door?

- A Detroit health agency has launched emergency mobile units to help people in a mental health or substance abuse crisis

- The idea is to address the needs people in distress before they end up in hospital emergency rooms

- The units allow patients to get one-on-one care and even follow-up appointments, while reducing encounters with police

DETROIT — From the darkest, most drunken days of his life, William Carroll finds humor.

His expertise, he quips, is a ‘doctorate’ in self-medicating.

“I had a Ph.D. in being a poor, hopeless drunk,” said Carroll, a peer support specialist at the Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network. Last month, the health agency began deploying unmarked, white passenger vans into neighborhoods as a response to growing mental health needs.

Maneuvering a Chrysler Voyager through city streets, Carrol’s hard-won experience might be what’s needed to offer a lifeline to someone going through an intoxicated dead end or mental health crisis.

“I didn’t know about community resources, but I knew there was a liquor store on nearly every corner, and — for a while at least — the liquor understood me,” said Carroll, 56.

Related:

- In Michigan, naloxone has reversed over 6,600 overdoses since 2020

- Michigan has just half the child psychiatrists it needs amid health crisis

- In Michigan mental health crisis, a tug-of-war over too few social workers

- Mental health crisis: Children at breaking point during COVID

Each weekday, four mobile response units fan out from a Milwaukee Street parking lot, heading toward the city’s parks, libraries, police precincts and neighborhoods.

The vans are part of a changing approach to mental health crisis care — one set out in 2020 federal guidelines intended to more proactively seek out people in (or barreling toward) a crisis. The idea is to have specialists identify and offer treatment to people in distress before they end up in hospital emergency rooms.

Officials call it a “no-wrong-door” approach, using 24-hour crisis call centers, mobile response teams and brick-and-mortar facilities to provide short-term care. The hope is these programs will lessen the burden on hospital emergency room staff while minimizing confrontations with police who are often ill-equipped to handle mental health crisis calls.

States are in varying stages of working toward that goal, according to an examination by KFF, a San Francisco-based health research nonprofit. The effort has been fueled, in part, by an infusion of 2021 American Rescue Plan Act funds.

While Michigan “is making great progress, we are still at the beginning of this system work,” Lynn Sutfin, a spokesperson for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, told Bridge Michigan in an email.

The Detroit-based mobile teams are among those on the front edge of those efforts.

For its part, the Detroit agency has operated a 24-hour crisis line (800-241-4949) since 2014 — long before the national 988 suicide and crisis line was established.

By spring, the four mobile units, which for now serve only adults, will expand to serve all ages and be available round-the-clock, said Grace Wolf, the network’s vice president of crisis services. The agency serves about 75,000 people with mental illness and serious emotional disturbance, substance use, and intellectual and developmental disabilities.

The organization is also building a 32-bed, short-stay facility, which is also expected to open by spring.

'Silently getting worse'

For too long, mental health experts have said, emergency rooms have been the default destination for crisis mental health care. That’s appropriate in many cases, especially for someone who risks physically harming themselves or others, said Dr. Antony Hsu, an emergency room physician for Trinity Health Ann Arbor Hospital, and spokesperson for the Michigan College of Emergency Physicians.

But it also has meant that hundreds of patients each year — many of them children — linger in emergency rooms, sometimes for days or weeks, as they wait for limited residential treatment beds elsewhere and staff scramble around them to treat other emergencies.

For those who are discharged, just one in three with a mental health or substance use disorder-related emergency department or hospital visit received follow-up care with a mental health specialist within 30 days, according to a recent report by the national mental health advocacy group, Inseparable.

That puts people at increased risk of relapse and readmission and is “ludicrous,” said Angela Kimball, senior vice president of advocacy and public policy at Inseparable.

The reasons for the delay in follow-up care are many — a lack of coordination for care, too few outpatient providers, lack of insurance, as well as the patient’s choice at times not to follow up. And Carroll, the Detroit peer support specialist, said emergency room settings can actually make a crisis worse for some patients.

“Imagine you’re agitated. You’ve got (patients with) gunshot wounds and noise and doctors running. And the priority is those gunshot wounds, and the heart attacks and the strokes,” Carroll said.

That’s not the ER staff’s fault, they have to prioritize saving lives. But then you have a person who is in a mental health crisis who “is silently just getting worse,” he said.

Carroll’s van partner, Virginia Harrell, agreed, saying emergency departments don’t provide the quiet and privacy needed for an important conversation.

“While you’re sitting there in a waiting room or a hallway with everyone looking at you, are you really going to open up about what’s really going on, the core issue — your sexual assault or some other trauma?” she said.

Mobile health teams can reach people in crisis at their homes or other points of crisis, cutting down the unnecessary and inappropriate ER visits. Services are voluntary and must be requested.

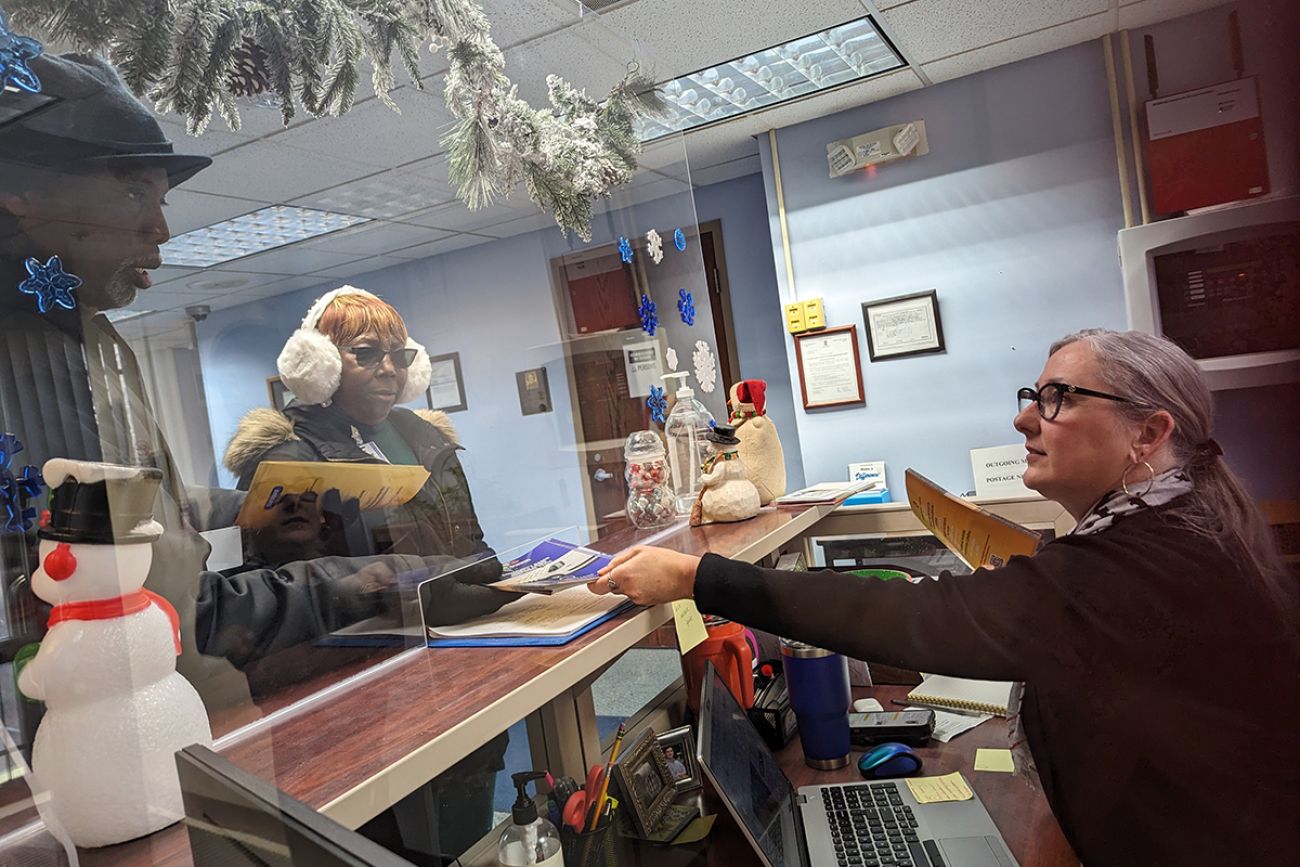

To meet federal guidelines, each mobile team is made up of a peer support specialist like Carroll — a person with their own experience facing mental health or substance abuse crises — and a master’s degree-level trained clinician.

Making themselves seen

It was a slow start to their shift Thursday morning, and Carroll and Harrell have spent much of their time in these first weeks dropping off fliers and introducing themselves at libraries, policy precincts and community agencies.

Still, the four teams have handled calls for an adult son whose mother reported he was hallucinating; a woman whose loved ones had seen her posting on social media that she intended to end her life, and another person caught in a crippling grief spiral.

Away from the chaos of an emergency room, the team can focus on a single person — a crucial component to unraveling a crisis, Harrell said.

They can make appointments for them to receive follow-up care.

“I want them to know I’ll do everything in my power to get what they need, to connect them to resources, and to understand them,” Harrell said. “The world can be a cruel place, and we all have to know there are people out there willing to walk with you.”

Resources to get help

Wayne County area residents — regardless of insurance status — can access the Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network Helpline at 800-241-4949 to get a unit deployed to their location.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, there are people who can help. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988. The group also lists resources for anyone who may be contemplating suicide: www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Some national and local resources are tailored to your needs — for youth, the LGBTQ+ community, Native Americans, Spanish speakers, military veterans, or those who are deaf or hard of hearing, for example.

Local providers can be found here through the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Crisis lines in Michigan also are searchable by county through the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

Other resources:

- The state’s Michigan Warm Line — 888-PEER-753 (888-733-7753) — provides people with mental illness with emotional support from a certified peer support specialist or peer recovery coach every day from 10 a.m. to 2 a.m.

- In Oakland County and the Upper Peninsula, residents may call the Michigan Crisis and Access line at 844-44-MICAL (844-446-4225) or chat live through this webpage.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!