Welfare changes have saved state money; fate of ex-recipients unclear

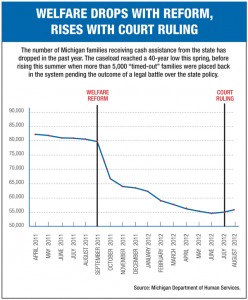

The number of Michigan families getting welfare checks from the state plummeted to the lowest level in more than 40 years just nine months after welfare reform was implemented. Twelve months in, the state is spending nearly $18 million a month less on cash assistance, the cumulative result of reform and an improving economy.

Those figures represent the clearest picture yet of the startling scope of the state’s reform efforts.

Less clear is the impact on the almost 15,000 families who lost benefits or are receiving cash assistance temporarily pending the outcome of a legal battle.

Orintha Petrimoulx, for example, leads a life today little different from a year ago when she was receiving welfare cash assistance each month. She and her child were living with Petrimoulx’s parents in Bay City then, and she’s living with them now.

The state of Michigan has saved thousands in cash assistance that would have gone to Petrimoulx over the last year, had it not been for welfare rule changes. Yet Petrimoulx is no closer to finding a job today than a year ago when she was on public assistance.

Is the 31-year-old a welfare reform success story? Or a cautionary tale of reform’s shortcomings?

"It cuts both ways," admitted Petrimoulx. "It’s a good thing because you don’t have all these people relying on the state who don’t want to work. But for me, I want to work, but there are no jobs around here."

Huge experiment ends first year

More than 9,000 Michigan families were removed from cash assistance last fall in what amounted to a massive experiment in social welfare policy – a number that grew close to 15,000 as months passed. No other state has removed so many families from welfare in such a short amount of time with so little notice.

Over the past year, Bridge Magazine and Michigan Radio have reported on the results of that social and economic experiment, chronicling the challenges of families as they adjust to life off welfare, and assessing the economic impact on state government and nonprofit charities.

The reform scorecard after one year:

* In 12 months, 14,823 families previously receiving cash assistance have been "timed out" of benefits by surpassing lifetime limits, according to data given by the Michigan Department of Human Services in a lawsuit challenging reform policies. Those include 9,410 cut off when the policy went into effect, and 1,767 who subsequently were terminated when they reached the cap. Another 3,646 who applied for aid in the past year were denied because they’d received aid exceeding the lifetime cap in the past.

* Those losing benefits over the past year were overwhelmingly urban poor. Decreases in just three of Michigan’s 83 counties (Wayne, Genesee and Kent) account for more than half the statewide decline in welfare cases.

* About 600 of the families removed from benefits are those in which the only able-bodied adult stays home to care for a severely disabled spouse or child.

* While state law protects families of the disabled from being cut off by Michigan’s 48-month cap on cash assistance, that exemption isn’t spelled out in a separate federal 60-month cap that hadn’t been enforced by DHS until last fall.

Proponents of reform predicted that families who had become dependent on welfare would get jobs after they were kicked off the dole. While the state unemployment rate has declined from 9.9 percent in October 2011 to 9.3 percent in September, it’s unclear how many former welfare recipients are employed.

11,000 Michigan families confront the unknown(October 2011)Cuts don’t fall evenly across Michigan (October 2011) 11,000 Michigan families confront the unknown(October 2011)Cuts don’t fall evenly across Michigan (October 2011)Rep to recipients: ‘Man up’ and feed family (October 2011) What will they do? (October 2011) Welfare reform leaves families without a net, and off the radar (February 2012) Daily life gets harder for three Michigan families (February 2012) More families set to lose welfare assistance (February 2012) 27 Mich. counties dodged welfare cuts (February 2012) Welfare reforms put care-givers in a wrenching bind (March 2012) Welfare reform: Back to the drawing board (March 2012) Welfare reform results: few jobs, few state answers, refuge in a vacant home (July 2012) Some Michigan welfare recipients get reprieve (July 2012) Center for Michigan, Bridge win battle for transparency on welfare records (August 2012) |

DHS isn’t tracking the families to determine how they fared. A study conducted by a volunteer in the Jackson County DHS office found that 68 percent of former recipients were unemployed; another 14 percent had jobs providing less money than what they were receiving on cash assistance.

A higher percentage of cash recipients are enrolled in the state’s job training program, JET (Jobs, Education and Training) than at any time in the program’s history – hitting 50 percent for the month of July, according to DHS.

Critics warned of increased homelessness. But a year later, there’s no clear evidence of an increase in homelessness. Eric Hufnagel, executive director of the Michigan Coalition Against Homelessness, said he doesn’t have data or anecdotal impressions to indicate whether homelessness is up or down in the last year.

"I worried at the time that these people would just disappear – that we’d never know what happened to them," said Judy Putnam, communications director for the Michigan League for Public Policy (formerly the Michigan League for Human Services). "Do we know how many found jobs? How many hours they’re working? How much they’re making per hour? There’s no way to know."

Size of drop surprises

What we do know is that reform has shaved the welfare rolls much more expected.

The Family Independence Program -- generically called welfare -- is run by DHS, but is funded primarily with federal dollars. It provides cash to low-income families with minor children, as well as to pregnant women. In Michigan, a family of three must make less than $815 a month (less than $10,000 a year) to qualify for help. (Families receiving FIP aid almost always are eligible for other assistance programs, such as food stamps, which were not affected by welfare reform.)

In September 2011, the last month before time limits were put in place, almost 80,000 Michigan families received cash assistance through FIP.

By June, 2012, that number had dropped to about 55,000 – a decline of 31 percent in nine months.

During that same time period, welfare payments dropped by more than half –from $44 million to $20 million in nine months.

Beginning in July, the number of welfare cases increased as a result of almost 6,000 families who were "timed out" being placed back on the rolls -- at least temporarily -- while a lawsuit challenging the policy winds its way through the courts. But even with those families receiving benefits again, Michigan is delivering cash assistance to 18,000 fewer families than before welfare reform took effect.

Those still receiving aid are getting smaller checks -- the average payment was $552 per month before reform, and was $428 in September. That’s a result not of lowered benefit rates, but smaller family size; an unexpected result of welfare reform is that families with more children were more likely to be "timed out" than families with fewer children.

Not all of the downward swing in cash assistance is attributed to welfare reform; welfare rolls had been dropping for months before reform took effect last fall -- and an improving economy has helped more families find work. Families cut off by time limits account for 61 percent of the drop in cash assistance.

The state doesn’t have a firm figure on how much of that savings is the result of welfare reform. The combination of improving economy and reform that kicked many long-time recipients off the dole has been an unanticipated savings for the state. The state spent $17.9 million less on cash assistance in September 2012 than a year earlier, according to DHS statistics.

Unclear if dropped families found work

There was never any doubt that welfare reform would save the state money – fewer families on the rolls make that inevitable. But the reform was pitched also as a way to help families reach self-sufficiency. "People will find their way in life," said reform sponsor Ken Horn, R-Frankenmuth, last fall. "They’ll pick up a hammer or a paint brush and man up and feed their family."

But whether that has happened is unclear. The lack of data on the families is "an opportunity lost," Putnam said. "Everybody wants our state to reduce poverty and see families climb to self-sufficiency, but we don’t know that this has had any impact in achieving that at all."

DHS disagrees, pointing to the fact that only 6 percent of eligible "timed out" families took part in a three-month rent/mortgage assistance program aimed at helping families transition out of cash assistance. When a court ruling in June allowed "timed out" families to sign back up for benefits, at least while the case is being adjudicated, 62 percent of families reapplied, according to DHS data. That leads department officials to surmise that thousands of families who had been on welfare for a minimum of four years no longer need assistance.

"With the governor’s pro-growth agenda helping the state’s economy improve, we expect that more and more individuals will be able to find work. This will naturally lead to fewer people on FIP, which is a good thing," DHS said in written statement released to Bridge Magazine. "Also, changing the culture from an entitlement to a work program should also lead to people not needing FIP for as long as folks were on it in the past."

Putnam said DHS’ rosy view of the impact of welfare reform runs counter to what she’s heard: "It’s all anecdotes, but … I haven’t seen any good anecdotes. Where are the good stories about people who lost their benefits and then went out and got a good job and are supporting their families?"

Senior Writer Ron French joined Bridge in 2011 after having won more than 40 national and state journalism awards since he joined the Detroit News in 1995. French has a long track record of uncovering emerging issues and changing the public policy debate through his work. In 2006, he foretold the coming crisis in the auto industry in a special report detailing how worker health-care costs threatened to bankrupt General Motors.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!