Pure slacking -- Michigan falters on conservation

Images of children frolicking on scenic beaches fill a television screen as the soothing voice of actor Tim Allen narrates the commercial promoting Michigan as the place to spend “the perfect summer.”

A line you won't hear Allen speak: Beach closures due to bacterial pollution -- contamination linked to fecal matter -- have doubled in the last decade.

While the visually stunning Pure Michigan advertising campaign has bolstered the state’s battered image and attracted millions of tourists, who have pumped billons of dollars into an ailing economy, state lawmakers have gutted programs designed to protect the natural resources that the advertising campaign promotes.

The divergent trends has some conservation leaders worried that the state is jeopardizing the ecological health of lakes, beaches and natural areas that are pillars of the Pure Michigan campaign -- and of Michigan.

“What’s been happening is kind of like someone putting pretty paint on a house that is structurally unstable,” said Rebecca Humphries, who was director of the Michigan Department Natural Resources and Environment from 2006-2010. “I think there is a disconnect.”

Humphries said deep cuts in conservation programs over the past decade could come back to haunt the state and undermine the Pure Michigan campaign. It may already be happening, according to government data and interviews with state officials.

Consider:

* Beach closures in Michigan have more than doubled in the past seven years.

* Michigan’s popular state parks system has a backlog of projects that totals $341 million. Even with increased funding, it could take decades to complete all of those projects.

* Michigan, once a national conservation leader, was in the bottom four states by conservation funding in a 2008 report.

* The DNR’s forest fire-fighting crew was 20 percent smaller than minimum staffing levels when a lighting strike in 2007 triggered a wildlife fire in theUpper Peninsula. Fueled by high winds, dry conditions and an understaffed crew of first responders, the Sleeper Lake fire near Newberry burned 18,000 acres of state forest and cost the DNR $7.5 million.

The state’s current forest firefighting crew of 72 is half of the optimum staffing level.

* The state knows the location of nearly 9,200 leaking underground storage tanks, but has nowhere near the sums to clean them up. Left unchecked, those sites could poison groundwater and drinking water wells with a variety of harmful toxins.

* The Lake Huron salmon fishery has vanished, the result of invasive mussels disrupting the food chain and government agencies in Michigan and Canada stocking too many fish in the lake, according to Jim Johnson, manager of the state's Alpena Fisheries Research Station.

* The number of master angler awards the DNR issues for large fish has dropped by 33 percent since 2001. Much of that decline is due to salmon in Lake Michigan shrinking after invasive quagga mussels disrupted the food chain.

Beach closures are one of the most obvious indicators of environmental quality. On that count, Michigan appears to be backsliding.

The percentage of beaches closed by bacterial pollution (linked to fecal matter) has increased from 10 percent in 2003 to 24 percent this year, according to state data. State officials blame the increase on polluted stormwater that drains off streets and parking lots and is often discharged onto beaches.

Whatever the cause, beach closures don’t help efforts to promote Michigan as a pristine recreational paradise.

“Obviously, we want the beaches to be open as much as possible,” said George Zimmermann, vice president of Travel Michigan. “The scenery, the quality of the experience is what Pure Michigan is about. Any challenges to that are a concern.

Tourism is credited with $17 billion in spending in Michigan in 2010, according to a survey done by the Virginia-based D.K. Shifflet & Associates. The state also points to the survey's finding that tourism accounted for 153,000 jobs in the state in 2010.

The Pure Michigan campaign, which launched in 2006, has attracted 7 million visitors to the state. The program generates $3.29 in economic benefit for every $1 spent promoting Michigan, according to state data. Zimmermann said a healthy environment is essential to the Pure Michigan campaign.

“Just look at our TV ads -- it’s obvious that Michigan’s natural environment is a significant part of what we are promoting to attract visitors, create jobs and generate revenue for the state,” Zimmerman said.

Yet, state funding for environmental protection programs has plummeted since 2001.

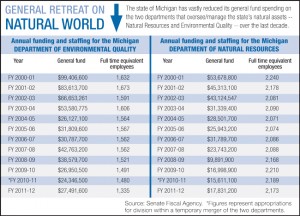

The state’s general fund support for the DEQ has decreased by 72 percent since 2001. Total state spending on the DEQ has increased during that same period; but when adjusted for inflation, total DEQ spending has decreased by 20 percent.

The number of DEQ staffers has been reduced 18 percent since 2001, meaning there are fewer regulators to keep tabs on air and water quality, monitor construction in wetlands and sand dunes and penalize polluters.

The number of DEQ staffers has been reduced 18 percent since 2001, meaning there are fewer regulators to keep tabs on air and water quality, monitor construction in wetlands and sand dunes and penalize polluters.

Meanwhile, there are 9,199 leaking underground storage tanks that need to be cleaned up. While some work is under way, Michigan is a long way from meeting its own standards for remediation.

Bill Rustem, director of strategy for Gov. Rick Snyder and an environmental adviser to Gov. Bill Milliken in the 1970s, said the administration is not content with the situation. Rustem said the governor wants to invest more in infrastructure, particularly sanitary sewer systems and green infrastructure, to reduce stormwater runoff and decrease the incidence and volume of combined sewer overflows. DEQ Director Dan Wyant said the department would do a thorough performance analysis of the leaking underground storage tank program. He said the program is not working as intended, because a large portion of the money meant for cleanups was diverted elsewhere to help balance the state budget.

General fund support for the Department of Natural Resources -- which manages fish and wildlife programs -- has dropped by 66 percent since 2001. Total state spending on DNR programs, when adjusted for inflation, has increased by less than 1 percent since then.

“It’s true that general fund support for the DEQ has declined and staffing levels are down significantly. But our gross funding level is up and we’re spending more as a department than we ever have,” said Wyant, who was appointed DEQ director after Gov. Rick Snyder took office in 2011.

Much of the increase in the DNR’s budget in recent years has come in the form of federal grants and permit fees that industries pay the agency. Some of that federal money will evaporate in a couple of years, said Wyant, who oversees DEQ, DNR and the Agriculture Department as part of Snyder's Quality of Life group in the Cabinet.

The DEQ can do a better job of preserving the state’s natural resources, Wyant said, but he believes the agency must do that by becoming more efficient and developing “partnerships” with the industries it regulates.

“It doesn’t mean we’re going to give up regulations or don’t go after the bad actors,” he said. “It means we’re going to go after the 75-80 miles per hour citations instead of the 71 miles per hour citations.”

Wyant said the first priority of all state agencies is to revitalizeMichigan’s economy. “It’s true we’d like to have more resources but it’s important that we get the economy back on track first,” Wyant said. “The DEQ can be a part of that by not being a hurdle to economic growth.”

Falling behind other states

In the 1970s, Michigan was considered a national leader in conservation programs. It was the first Great Lakes state to ban phosphorus in laundry detergent, a move that helped Lake Erie recover. Michigan also was the first state to ban the insecticide DDT, which killed birds and nearly wiped out bald eagles.

Tougher state and federal regulations enacted since 1970 have brought about dramatic improvements in air quality, water quality and the health of fish and wildlife, according to government data.

But a combination of factors over the past decade -- including Michigan’s economic decline, changes in legislative priorities and the expiration of bond programs that funded pollution cleanups -- has hurt the state’s environmental protection and conservation programs, according to Humphries.

Michigan ranked 47th among the 50 states for conservation funding, according to a 2008 study by Michigan State University’s Land Policy Institute.

Humphries said the effects of the state’s funding are evident in such programs as state forest maintenance and firefighting, where funding and personnel have been cut. The result: Small fires are more likely to become large fires that burn more land and homes built in wooded areas. A 2011 internal DNR audit found that 70 percent of DNR's firefighting equipment is past its replacement schedule.

“Our forest fire-fighting staff is well below national standards, we’re always one disaster away from having to close state parks, we don’t have money to maintain roads and trails in state forests and we still have contamination sites that we can monitor but we can’t clean up,” Humphries said. “All of these issues concern me and they should concern most people in Michigan.”

During Humphries' tenure as DNR director, general fund support for the agency dropped from $31.7 million in FY2007 to $16.9 million in FY2010. Humphries blamed the deep and sustained cuts over the past decade on lawmakers and the public assigning less value to conservation programs than they did in the past.

The steady decrease in state funding for the DNR and DEQ is in sharp contrast to funding for Michigan’s Strategic Fund, the economic development agency that houses the Pure Michigan campaign.

State support for the Strategic Fund has doubled over the past decade, from $65 million in 2001 to $134 million in fiscal 2012. The state will spend $25 million on the Pure Michigan campaign in FY2012. That nearly equals the amount of general fund money the Legislature allocated to the DEQ.

Almost every state agency has experienced budget cuts since 2001, but few have been hit as hard as the DEQ.

The Michigan Legislature, which controls funding for all state agencies, has suffered little during the state’s budget crisis. The Legislature’s general fund budget has been cut by just 6 percent since 2001, according to state data.

Republicans, conservation leaders at odds over funding

Despite the backlog of pollution cleanups, lack of maintenance of state forests and pressing infrastructure needs in state parks, one Republican lawmaker said the DNR and DEQ are adequately funded.

Ryan Mitchell, a spokesman for Sen. Mike Green -- who chairs the DNR and DEQ subcommittees of the Senate Appropriations Committee -- said budget cuts over the past decade have made those agencies more efficient and reduced administrative overhead.

“While we did reduce the administrative budgets and size of the two departments in general fund dollars, there are still plenty of resources available that go directly to the mission, not to sustaining bureaucracy we can’t afford,” Mitchell said.

Officials at the Michigan Environmental Council and Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council, however, said Gov. Snyder’s 2012 budget jeopardized the Pure Michigan campaign by further reducing funding for conservation programs. The governor’s budget cut DEQ funding by 15 percent and DNR funding by 13 percent.

“We’re concerned about the long-term sustainability of Pure Michigan if we continue to underfund pollution cleanups and environmental protection programs. Eventually, it will catch up to us,” said James Clift, policy director at the Michigan Environmental Council.

Michigan hasn’t had a major environmental disaster since the 1970s, when the toxic flame retardant PBB was accidentally mixed with cattle feed. The incident poisoned the state’s milk and meat supplies and became the nation’s largest case of chemical contamination.

Michigan was home to the Midwest’s largest oil spill in 2010, when a ruptured oil pipeline dumped 840,000 gallons of crude oil into the KalamazooRiver. That incident didn’t strain the DEQ or DNR budgets because federal agencies took the lead in supervising the cleanup, said Humphries, who now works for the advocacy group Ducks Unlimited.

The longtime DNR employee said she wonders what it would take for Michigan lawmakers to once again make conservation programs a priority.

“Are we going to have to have another crisis like PBB before we start investing again in conservation and environmental protection?” Humphries said. “God, I hope not.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!