Michigan absentee ballots: What happens after vote, why they may delay results

- Election officials say absentee ballots take longer to count

- The labor-intensive process may delay election results

- Lansing clerk showed Bridge the process

LANSING — Michigan voters have already had weeks to cast absentee ballots before the Nov. 8 election, but they can’t actually be counted until Election Day — which could delay some results until the following day.

The lengthy counting process fostered misinformation in 2020, when initial unofficial results from in-person voting showed then-President Donald Trump with an early lead in Michigan that disappeared as absentee ballot counts came in favoring Democrat Joe Biden.

While fewer voters are expected to cast ballots this year than they did in the presidential contest, officials still expect half of the votes to be absentee, and counting may not be complete in some areas up to 24 hours after polls close.

Related:

- Michigan absentee voting surges in GOP-leaning counties, slower in Detroit

- As Michigan election nears, some apprehension over strife at polls

- Jocelyn Benson: ‘We’ve delivered on our promises.’ Republicans aren’t so sure.

If the governor’s race or other contests are close, a clear winner may not be immediately known.

“There's a reality that the workflow of counting absentee ballots is really time intensive,” Ottawa County Clerk Justin Roebuck, a Republican, said this week in a pre-election media briefing.

“The important thing is that we’re getting it right,” added Roebuck, whose office will compile and publish results from local communities. “That’s something that we’re conscious of, for sure, going into this process.”

So why does it actually take so long to count absentee ballots? And what happens to them after they’re submitted by mail, drop box or to a local clerk?

Bridge Michigan recently spent an afternoon with Lansing City Clerk Chris Swope, who walked us through required and optional steps that his team of about 50 workers did not complete until about 10 a.m. the morning after the election in 2020.

Here’s a breakdown of what has already happened – and what will happen – with absentee ballots, which you should put in the mail soon but can return to your local clerk’s office until polls close at 8 p.m. on Election Day. You can also spoil an absentee ballot if you want to change it or vote in-person.

STEP 1: COLLECTING BALLOTS

The first step in the absentee ballot process is obvious: collection.

That’s easy enough for mail-in ballots, which are sent directly to clerks or other municipal facilities where they will be counted. But it’s a more complicated for communities with several drop boxes, which you find the location of here.

Lansing has 15 drop boxes throughout the city. Swope hired a municipal worker whose primary assignment is driving to each of those drop boxes every day, emptying them and delivering their content back to the election unit offices.

“He's a stay-at-home dad, so it kind of worked perfectly for him,” Swope said of the drop box collection gig. “He can do his whole job in a couple of hours.”

Under a new law finalized weeks ago by Michigan’s Republican-led Legislature, election clerks must keep chain-of-custody logs documenting the date and number of absentee ballots collected from each drop box, along with the name of the person who collected them.

Drop boxes must also be routinely inspected, and any units installed in the last two years must be continually monitored by video surveillance. (The video requirement does not apply to older drop boxes installed before October 2020).

Those new rules won’t mean many changes in Lansing, Swope said. The city already kept chain-of-custody logs for absentee drop box collections and had video cameras on most of its drop boxes. The four boxes that didn’t have cameras are each at fire stations that are continually staffed, but Swope said he recently ordered new cameras for those as well.

STEP 2: CHECKING SIGNATURES

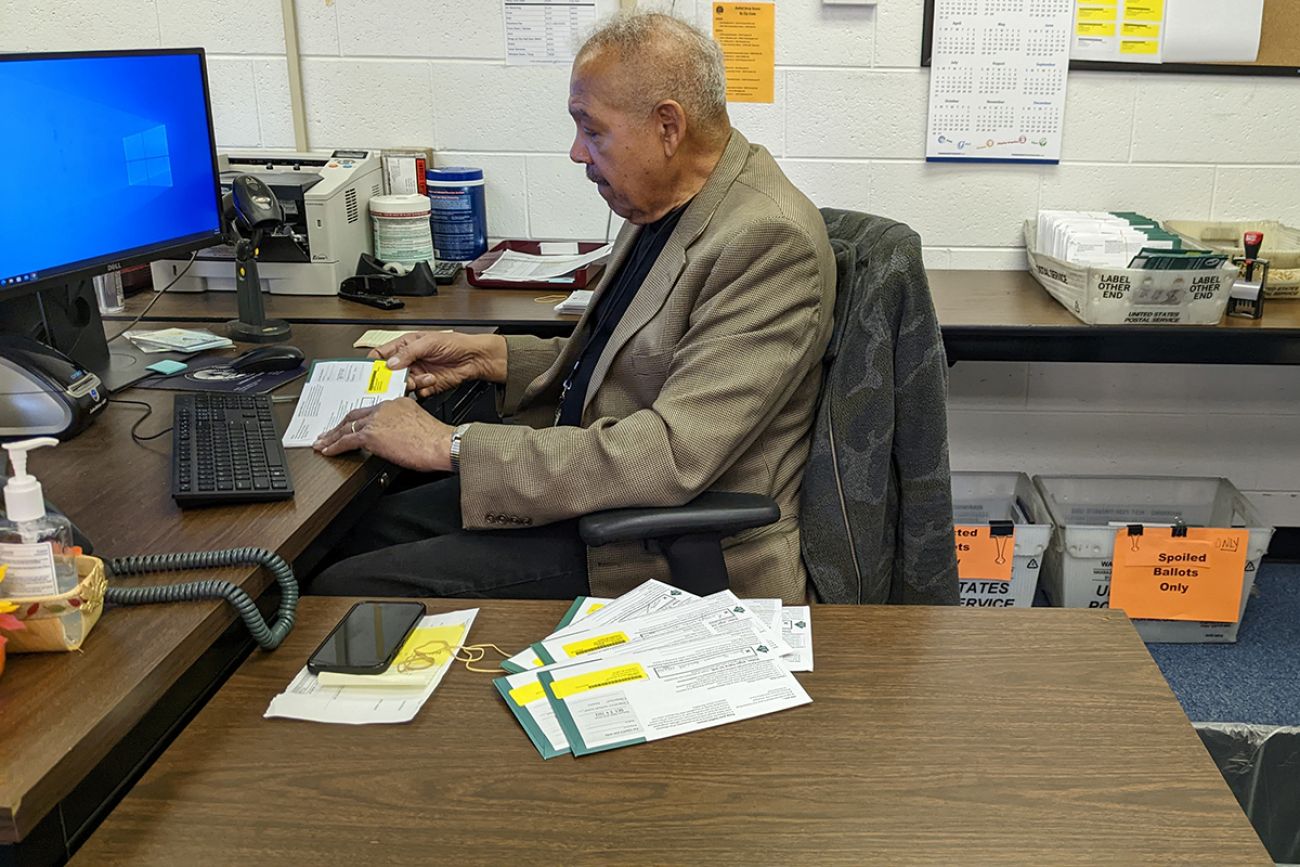

Once an absentee ballot arrives at the Lansing election office, a city staffer sitting in front of a computer scans a barcode on the outside of the envelope. That marks the ballot as “received” in an electronic voter database and creates a digital paper trail to prevent that voter from casting another ballot (unless they later ask to spoil their ballot and cast another, which is allowed).

Scanning the ballot barcode prompts a pop-up window on the election worker’s screen that will show any stored versions of the voter’s signature. That’s usually just a driver license signature from the Secretary of State’s Office. But sometimes there is also a second signature if the person registered to vote with a local clerk instead of at a motor vehicle office.

The election worker then compares the signature on the outside of the absentee ballot application with the version(s) on their computer screen. Most of the time, signatures match. But if they don’t, the clerk’s office tries to contact the voter to give her a chance to explain the discrepancy — maybe they had a stroke, Swope said as an example — or prove that the signature is legitimate, so her ballot can still be counted.

STEP 3: SORTING AND STORING

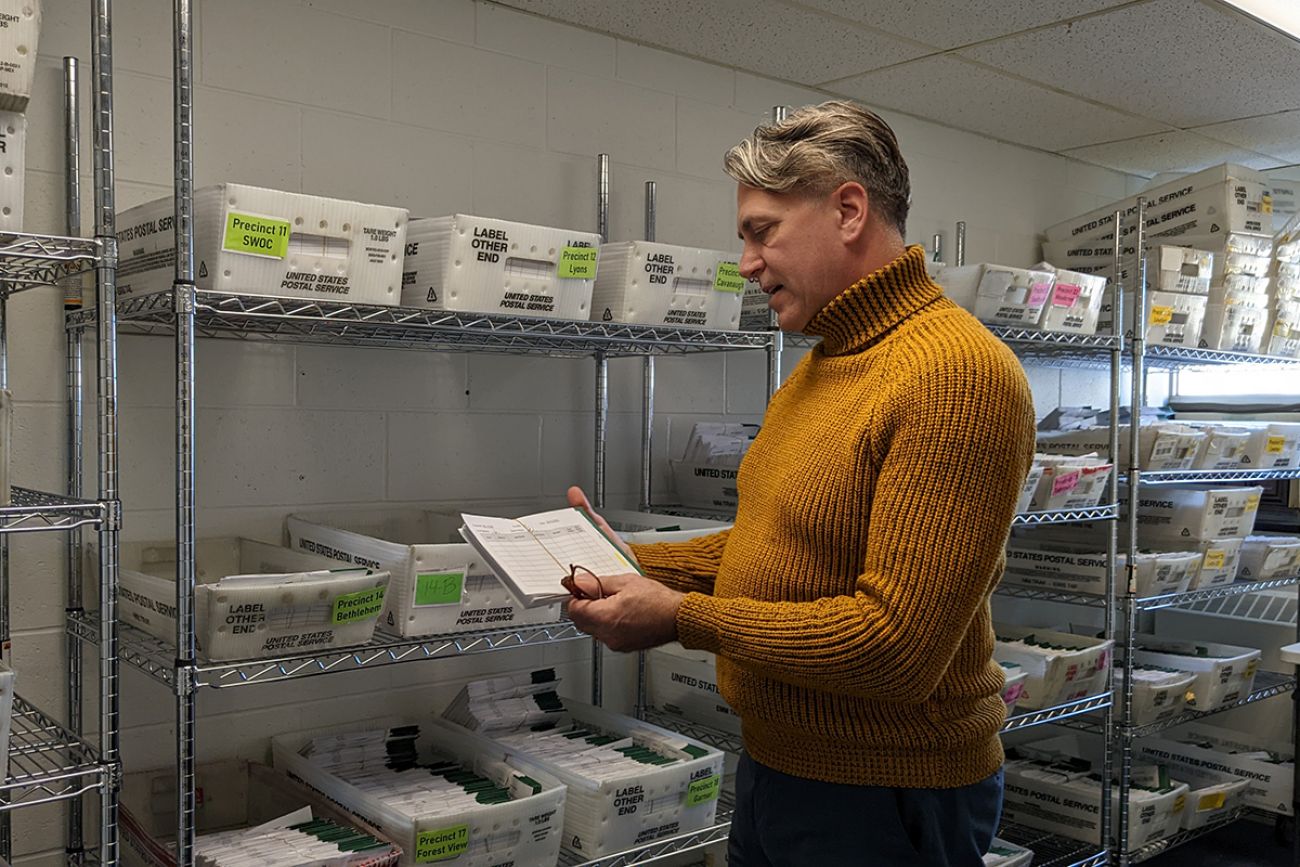

Once absentee ballots are checked in and the voter’s signature is verified, they are then stored in the clerk’s office until Election Day nears.

In Lansing, staffers sort absentee ballots by precincts and then place them into separate bins. Each day, any ballots added to a precinct bin are first bundled together with a cover sheet indicating how many ballots were added and by whom. Workers also double-check ballot counts against totals in the computer system to make sure all envelopes are accounted for.

That system, which may differ by local jurisdiction, makes it easier to go back and find a ballot before Election Day if needed, Swope said. For instance, if a voter who cast an absentee ballot dies before Election Day, that is not supposed to be counted, so staff must find it and remove it.

In Lansing, all still-sealed ballots are stored in a locked room that is “inside of a locked office suite inside of a building that’s locked when we aren’t here with a parking lot with a gate that is closed,” Swope said from inside that room.

“And,” he added, “it’s a former military facility.”

STEP 4: PRE-PROCESSING (OPTIONAL)

Anticipating a flood of mail-in voting in 2020, Michigan lawmakers passed a temporary law allowing clerks in larger municipalities to “pre-process” – but not count – absentee ballots in that election.

That law is back, and somewhat expanded for 2022. Under a new version the GOP-led Legislature passed earlier this month, clerks in communities with at least 10,000 residents will be allowed up to two days to pre-process absentee ballots, beginning Nov. 6.

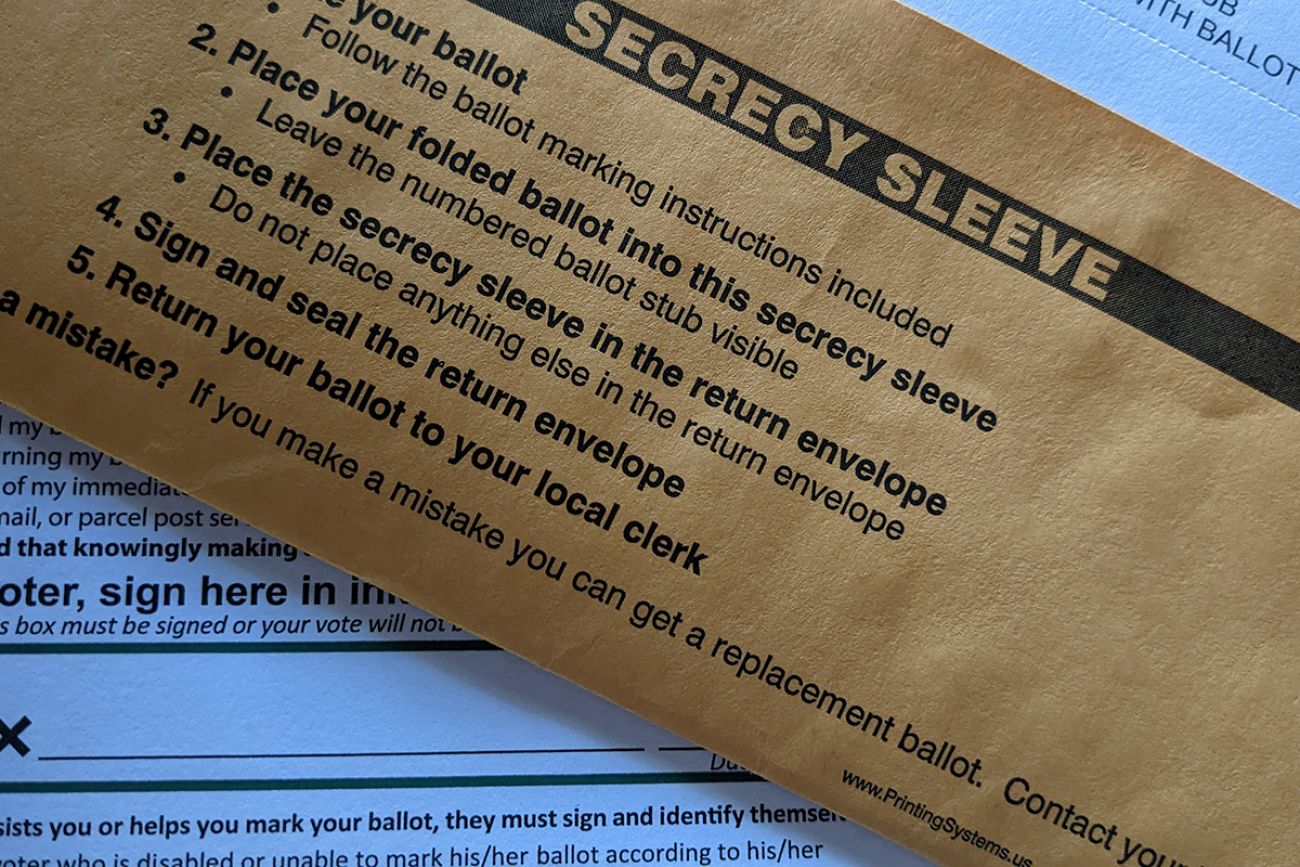

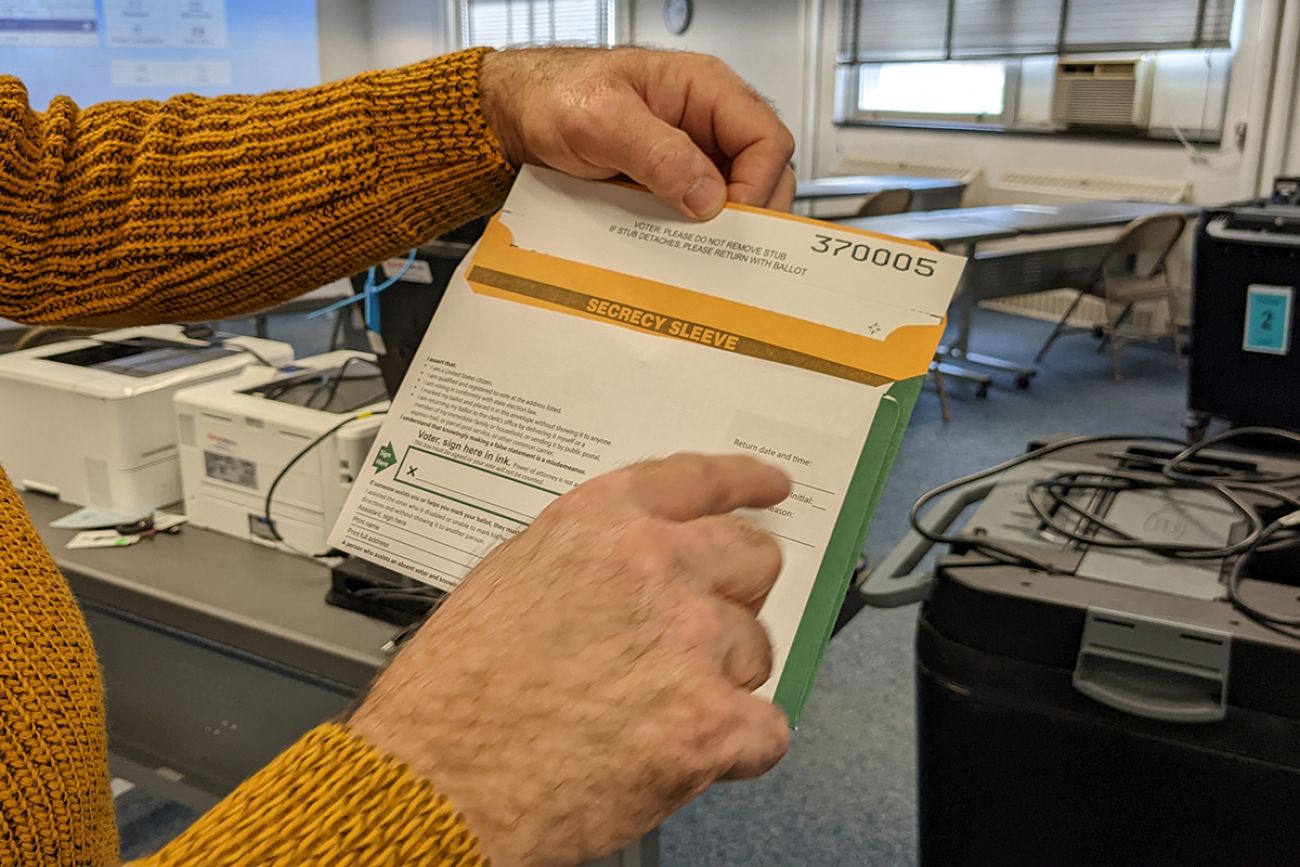

In jurisdictions that decide to utilize the option, election workers will be able to open the outer return envelopes on absentee ballots, but they will not be able to take ballots out of the internal secrecy sleeve, and they will not be able to flatten those ballots to prepare for tabulation.

If you wonder why states like Florida and Ohio are quicker to report results than Michigan, this is why. Those states both allow clerks to not only open envelopes weeks before the election, but to also actually feed absentee ballots into tabulators without computing or reporting any results.

In Michigan, 39 jurisdictions have told the state they will do at least one day of pre-processing to prepare absentee ballots for counting on Election Day. Detroit, the state's largest city, plans to conduct two days of pre-processing. Grand Rapids will use one day.

In those communities, election workers (at least one from each major political party) will have to record the number of absentee ballot outer envelopes they open each day. Election challengers trained by political parties and nonprofits will be allowed to observe the entire process.

Despite the new law, Swope said he won’t do any pre-processing this year in Lansing. He tried it in 2020, but the process was cumbersome and caused confusion between election workers who opened envelopes on Monday and those who actually counted them Tuesday, he told Bridge.

“It was a new process, and we weren’t able to work out any kinks,” Swope said.

STEP FIVE: PREPARING TO TABULATE

When polls open at 7 a.m. on Nov. 8, election workers across the state will be allowed to open all absentee envelopes, remove ballots from secrecy sleeves and then flatten them so that they can be counted by tabulators.

In between, they’ll remove a numerical stub at the top of each absentee ballot, so there is no way for individual workers to determine whose ballot they are handling, a practice designed to protect the secret vote. Workers check to make sure the stub number matches the ballot envelope, which they’ll keep on file as another paper trail should questions arise.

Michigan law requires clerks to at least try to hire an equal number of Republicans and Democrats to serve as election workers (also known as election inspectors) from lists submitted by the parties. Whether they are able to do so often depends on which residents actually signed up to work the shifts.

Recruiting absentee ballot counting board workers can be a challenge because it is a demanding job, Swope said. Once workers arrive on Election Day, they are sequestered and not allowed to leave until polls close at 8 p.m.

In Lansing, election workers will prepare absentee ballots for counting one precinct at a time. The city speeds up the process by using four “slicer” machines that actually cut open the outer envelope, so workers have easier access to the secrecy sleeve and ballot contained within.

STEP SIX: DUPLICATING BALLOTS (IF NECESSARY)

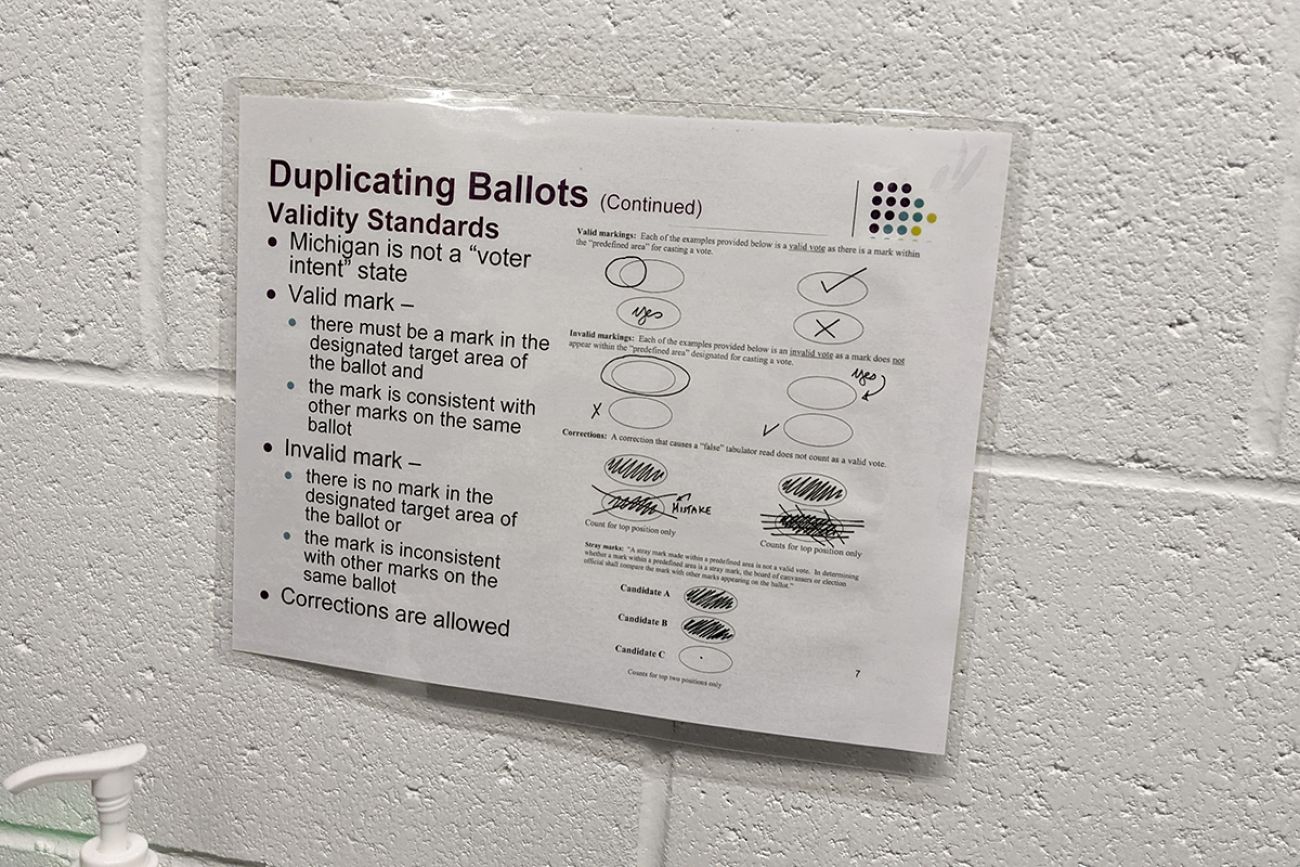

At least one Republican and one Democratic election inspector should also be present any time a ballot is “duplicated” in order to feed into a tabulator properly, Swope said.

That will only happen in limited circumstances. For instance, overseas military voters are allowed to email in their absentee ballots. Workers will have to “duplicate” them by filling in corresponding ovals on a physical ballot that can be fed into a tabulator.

A ballot may also have to be duplicated if a voter spilled coffee on it or tore it in a way that prevented a tabulator from counting it in its original form, Swope said.

STEP SEVEN: TABULATING BALLOTS

Now comes the fun part: Tabulation.

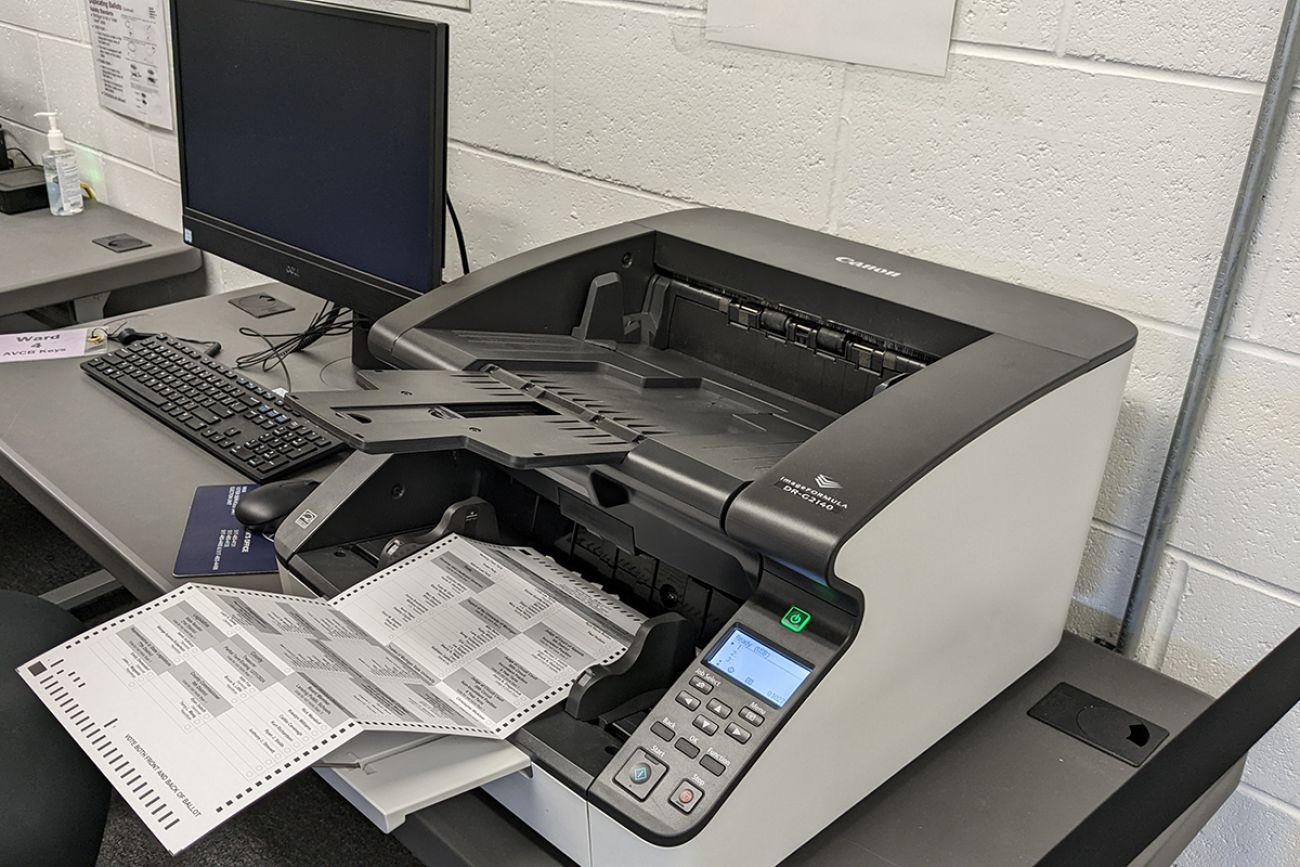

Once election workers have opened, flattened and stacked ballots from an entire precinct, they’ll carry them over to a neighboring room where a separate group of workers will actually feed them into tabulators.

Lansing owns four high-speed tabulators — some smaller communities don’t own any — that should be able to count about 30 to 40 ballots per minute, according to Swope. That’s much faster than you’ll see at the tabulators in polling places, which can only count about four ballots per minute, he said.

Each tabulator is wired to a computer, where a single election worker will log in using a key fob and access code before starting to feed stacks of ballots into the counting machines.

For every two tabulators, there is also a separate “adjudication” table that will always be staffed with at least one Democrat and one Republican who will work together to address any questionable ballots, Swope said.

Workers at the adjudication table will have their own computer, wired to the tabulator stations, where they’ll review images of any ballots with extra or unclear votes: A stray mark, an oval that was not fully filled or a write-in candidate the tabulator could not read on its own, for instance.

Those election inspectors will decide whether or how to count each questionable ballot. Their decisions will be recorded by the computer “so you could go back and review and question their decisions” if any controversy arises, Swope said.

None of the tabulators or adjudication machines are connected to the internet, and poll challengers from major political parties or credentialed nonprofits “can basically be anywhere throughout” the absentee counting board, Swope said.

STEP EIGHT: REPORTING RESULTS

Once the absentee ballots are fed through tabulators, local clerks must report unofficial results to county clerks (some cities do also publish their own local results separately) who will then post them online for the public to view.

This is another potential delay point because the state is “phasing out” the use of obsolete modems that many jurisdictions had used to transmit vote tallies from absentee counting boards and polling places, Michigan Elections Director Jonathan Brater said in August.

The move away from modeming in unofficial results is consistent with new federal standards, but the decision is also intended to counter “misinformation” about election security linked to modems in the 2020 election, according to Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson’s office.

Some local clerks are now expected to use secure FTP servers to electronically transmit unofficial results from their municipal offices to county clerks, Benson spokesperson Jake Rollow told reporters last week. Others will put the data on a thumb drive and physically drive it to the county clerk.

In Lansing, Swope already used an encrypted virtual private network (VPN) to send unofficial results and intends to do so again this year. Results won’t be made official until weeks later upon certification by county and state canvassers.

STEP NINE: FINALIZING THE ELECTION

Like in-person ballots, absentee ballots must be stored in approved storage containers after they are counted.

At the end of the process, election workers will seal and sign those containers, which will stay in the possession of local clerks and remain sealed unless a recount is requested.

Election workers will also sign tabulator tapes, printed election records from each machine. Local clerks will keep the ballots but send a statement of votes, poll books and other election information to county canvassers, which are bipartisan boards expected to certify results by Nov. 22.

County canvassers will review unofficial results to make sure the number of voters matches the number of ballots cast. Discrepancies will be reviewed by the canvassers and, in rare cases, may require the ballots be brought before the board in a public meeting.

The state board of canvassers then repeats the process and is expected to certify statewide results by Nov. 28.

Trump and his supporters pressured Republican canvassers to reject election results in 2020. But all counties and the state board ultimately certified results within required timelines and are prepared to do so again this year, said GOP state canvasser Tony Daunt.

"This is a very ministerial duty," Daunt said this week during a media event. “I was never a good math student, but I think I can handle the addition of 83 counties and determining that these are the results.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!