Educators see violation of trust in pension proposal

When Kathy Kapera started working as a Michigan teacher in 1976, she made about $7,000 a year. Over the course of her career -- most of it spent teaching hearing-impaired children in Royal Oak -- she earned a master’s degree, and steadily accumulated seniority and experience that all led to the moment in 2010 when then-Gov. Jennifer Granholm made her an offer she couldn’t refuse: retirement.

She was 58, her children grown, and she was ready to leave the grind behind. Even for a job that many taxpayers consider an easy one -- all that vacation -- actually doing it is something else.

“People thought it was a 9-to-3 job,” she said. “It never was. I worked from the time I got up until I went to bed -- papers, staying late, all of it. Summers I was taking workshops to learn more skills. It was never an easy job. But I loved it. “

Granholm’s plan was to ease the financial burden on school districts by thinning the ranks of older teachers and administrators earning at the top of their pay scales. Employees who left between July 1 and Sept. 1, 2010, got a slightly sweetened pension multiplier – 1.6 instead of 1.5. When Kapera took advantage of the offer, she expected she’d be getting the system’s excellent retiree health-care deal, with 90 percent of premiums paid by the state.

Granholm’s plan was to ease the financial burden on school districts by thinning the ranks of older teachers and administrators earning at the top of their pay scales. Employees who left between July 1 and Sept. 1, 2010, got a slightly sweetened pension multiplier – 1.6 instead of 1.5. When Kapera took advantage of the offer, she expected she’d be getting the system’s excellent retiree health-care deal, with 90 percent of premiums paid by the state.

Those retirees joined a system in which the average pension payout, for 2010, was $20,316, with an average annual health benefit of $22,092.

But under the draft of Senate Bill 1040 now before the Legislature, the state's premium share would drop to 80 percent. Kapera acknowledges the pain for her would be minimal; her husband has insurance, and is still working. What she objects to is the breaking of the promise -- implicit throughout her career, starting with that $7,000 salary – that her benefits would make up for the relative lack of financial compensation she would earn as a teacher.

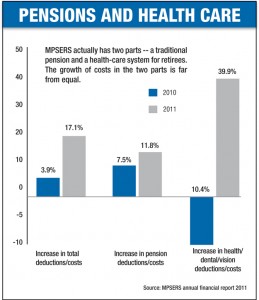

Those benefits are now under scrutiny, as unfunded pension and health-care obligations threaten school districts financially; the amount local districts must pay to support the Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System now stands at 24.46 percent of payroll, and is rising rapidly. It’s a fiscal burden that is leading districts to trim and outsource staff and cut programs. SB 1040 was written to address it.

Kapera, though, wonders if it isn’t going to have a long-term effect beyond the financial.

“People won’t be going into teaching,” she said. “We’ll end up with a shortage.” (Mlive.com reported last year that "Michigan colleges collectively graduate about 7,500 new teachers a year. The Michigan Education Association has estimated about 5,000 of them leave the state in search of work.")

Kapera isn’t pouting. Others share her concern that an essential bargain with public workers is being broken, and the state could suffer as a result.

“That's the trade-off: You go to the public sector and know you won't make as much as similarly educated people, but you do know you'll have a pension and health care when you retire. That's our concern, that we maintain that,” said Peter Spadafore, then the assistant director of government relations for the Michigan Association of School Boards. As districts cope with ever-increasing demands to improve student performance, they’ll need top teachers, Spadafore argued, and compensation packages are essential to attracting and retaining the best ones.

Fred van Hartesveldt knows the choices. Now 55, he faced a fork in the road in 1989, when he left his chosen profession of law to teach English. He now works at Grand Rapids Community College and serves on the board of the Coalition for a Secure Retirement. He testified before a Senate subcommittee against SB 1040.

“One of the things I testified to was that I was trading a potential for unlimited income for a regular salary, plus retirement, pension and health care,” he said. And while he doesn’t regret the choice -- “teaching is a lot more fun that law ever was” -- he’s aware that many of the things he bargained for are threatened.

“Nobody's happy about having to pay more money, or receive fewer benefits,” he said. “Reasonable people can acknowledge this system has financial problems, and have to do something to correct it. It's a question of how much and when.”

Several of his colleagues testified at the hearing about derailed plans to retire in their mid-50s and even younger, an age when private-sector workers are, for the most part, still in the work force. Van Hartesveldt cautioned observers that MPSERS includes more than just teachers, and that increasing contributions will hurt people already earning modest salaries, including custodians, bus drivers, secretaries and other support staff.

“If you're gong to do something, try not to hit (those with smaller pensions) the hardest,” he said.

Staff Writer Nancy Nall Derringer has been a writer, editor and teacher in Metro Detroit for seven years, and was a co-founder and editor of GrossePointeToday.com, an early experiment in hyperlocal journalism. Before that, she worked for 20 years in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where she won numerous state and national awards for her work as a columnist for The News-Sentinel.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!