Demystifying Michigan elections: What happens to ballots after you vote?

LANSING — Grouped. Counted. Stored. Counted again. Removed from envelopes. Counted again.

This is just a portion of the journey your ballot takes once you drop it off at your local clerk’s office or drop boxes if you vote absentee in the November general election.

More than 1.5 million people have already cast their ballot in Michigan, and an additional 3.5 million are expected to vote either absentee or in-person by the end of the day on Nov. 3, breaking state turnout records.

President Donald Trump and others have claimed without evidence that what happens behind closed doors with election workers is likely to become widespread fraud. State and local election officials insist there’s a robust system to catch fraud and to ensure every eligible vote counts.

Bridge asked Lansing City Clerk Chris Swope’s office to show how ballots are processed once voters turn them in and what protections are in place to ensure they remain secure.

The space and equipment will differ slightly depending on municipality — for example, smaller cities are less likely to be able to afford high-speed tabulators, which count ballots quickly — but Lansing’s ballot security measures are a fair reflection of how most cities store and process ballots, Swope said.

“Election workers are your neighbors, members of our community that are involved in every step of this process,” Swope said. “We all want to run an honest, fair election.”

Here’s what happens to your ballot behind closed doors.

Absentee ballots

Step 1: Log and check signature

Voters turn in absentee ballots by mailing them to the local clerk’s office, dropping them in a designated ballot drop box or by handing them in in-person at the clerk’s office.

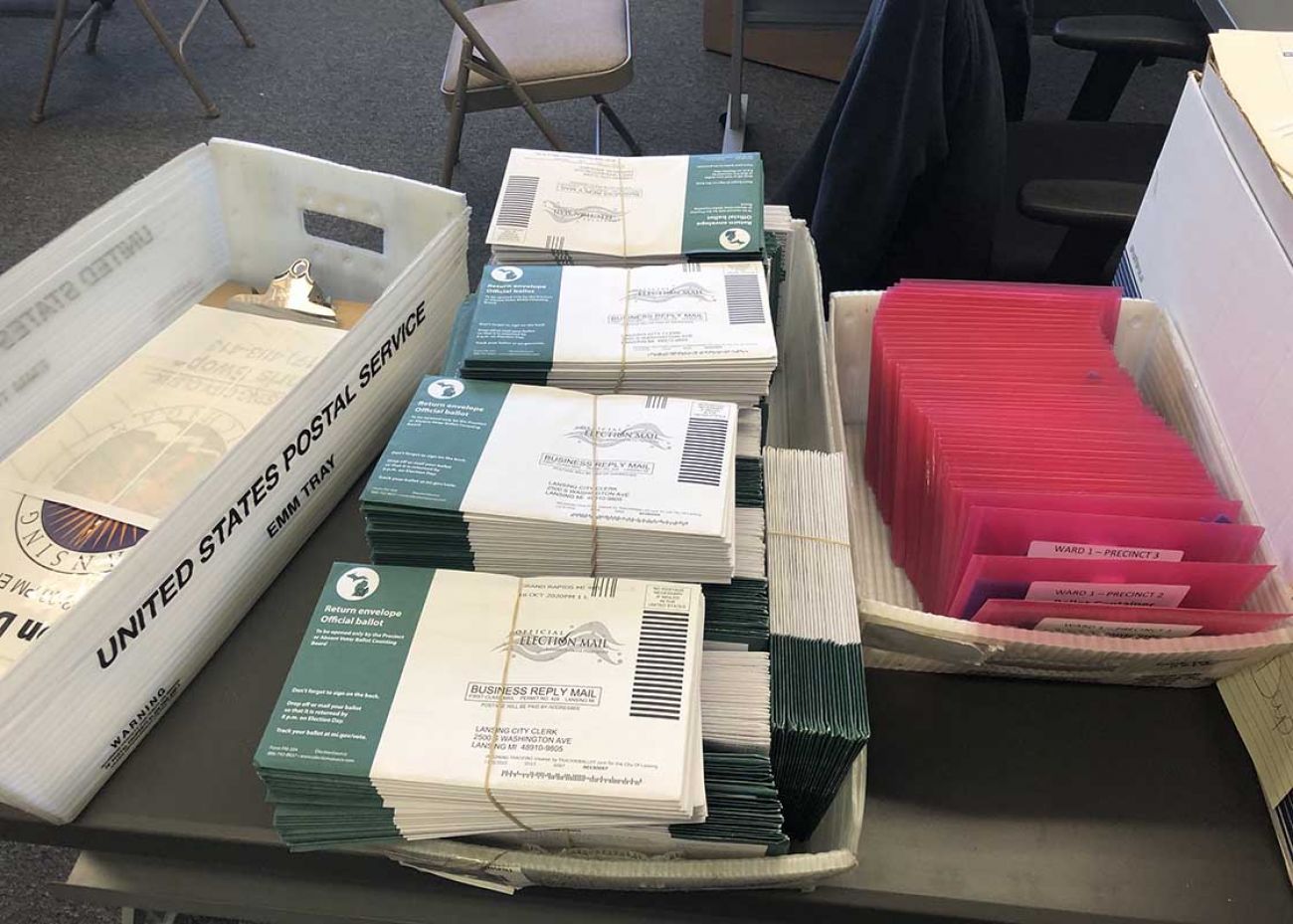

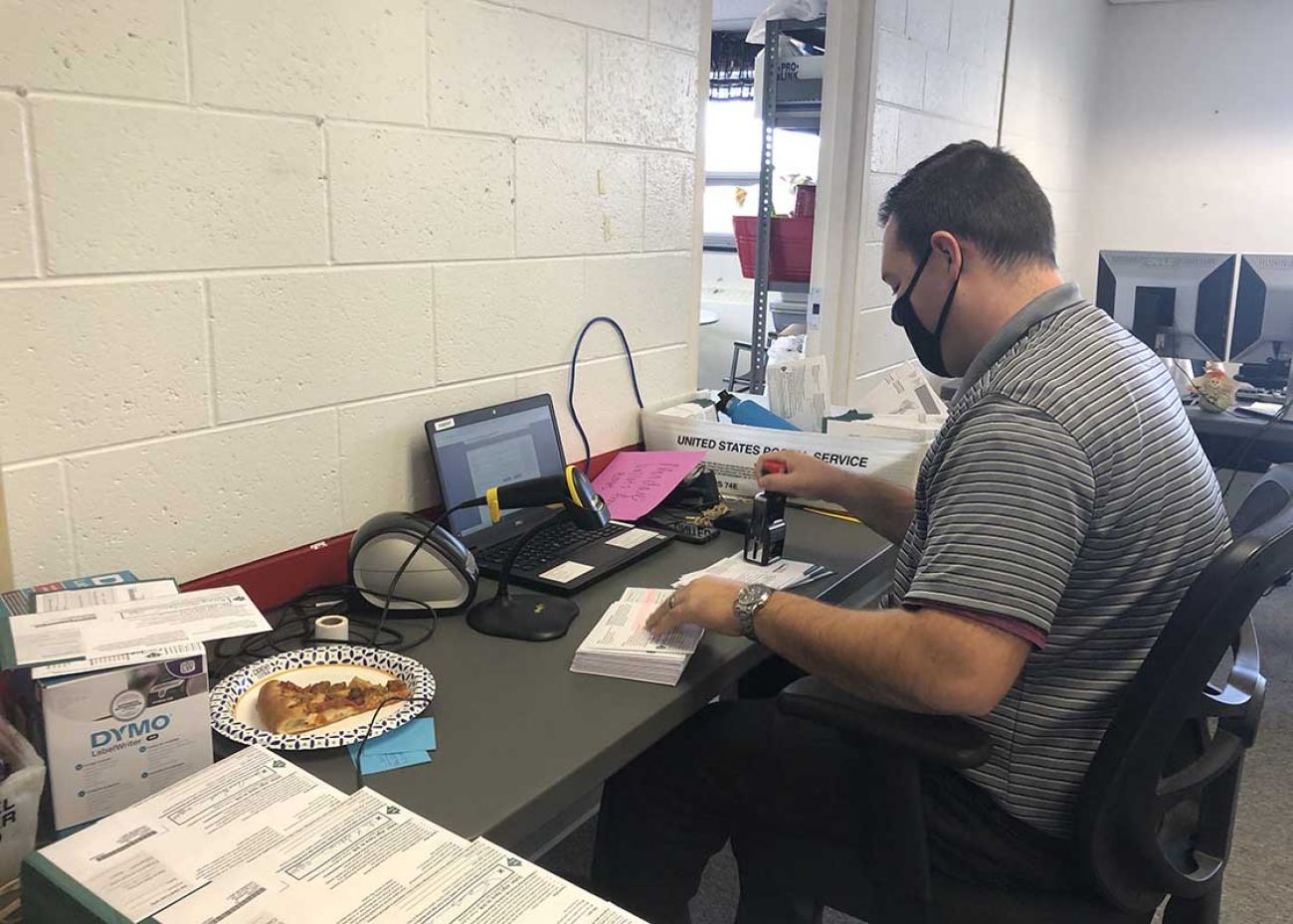

Clerks group absentee ballots into piles of 25 in the order they come in. They’re scanned into the clerk’s computer system and stamped with the date they were received.

Scanning the ballot will pull up the voter’s signature on file. A staff member checks the signature on the ballot envelope with the signature on file to ensure they match.

If the voter forgot to sign the envelope or the signature is significantly different than the one on file — or if someone else signed the envelope, such as the voter’s spouse or parent — the clerk is supposed to contact the voter by phone, mail or email within 48 hours and ask them to come in to correct it.

If the ballot is from a different jurisdiction, the clerk may deliver it to the proper precinct. As Election Day nears, clerks may notify voters and tell them to retrieve the ballot and spoil it and cast a new one before 10 a.m. Nov. 2.

As the ballots are scanned, the computer will keep a running total that is checked against the number of physical ballots before moving on to the next step. If the count is off, staff work backward to figure out what happened and correct it.

Step 2: Sort by precinct and check count again

The ballots are then sorted by the ward (there are four wards in Lansing) and precinct of the voter who turned it in.

At the end of each day, staffers print reports indicating how many ballots have been received per precinct. Staff count the ballots in each ward to ensure the numbers match what the computer has indicated.

Then, the ballots are moved into a storage room and added to a bin marking the ward and precinct number. Ballots are grouped in stacks of 50 and recounted against the computer total around once a week.

In the case that there is some change — such as a voter dying or registering in a new jurisdiction before Election Day — their ballot is pulled from the stack and destroyed.

The ballots will stay in storage until the day before the election or until Election Day in smaller cities.

Step 3: Pre-process ballots in large municipalities

Michigan cities with populations over 25,000 can begin pre-processing ballots from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. the day before the election this fall due to a recent state law change.

Ballots are returned inside secrecy sleeves, which are put inside the larger green-and-white envelopes that are used for mailing.

During pre-processing, election workers pull ballots from storage and take them out of the outside envelope, but not the secrecy sleeve.

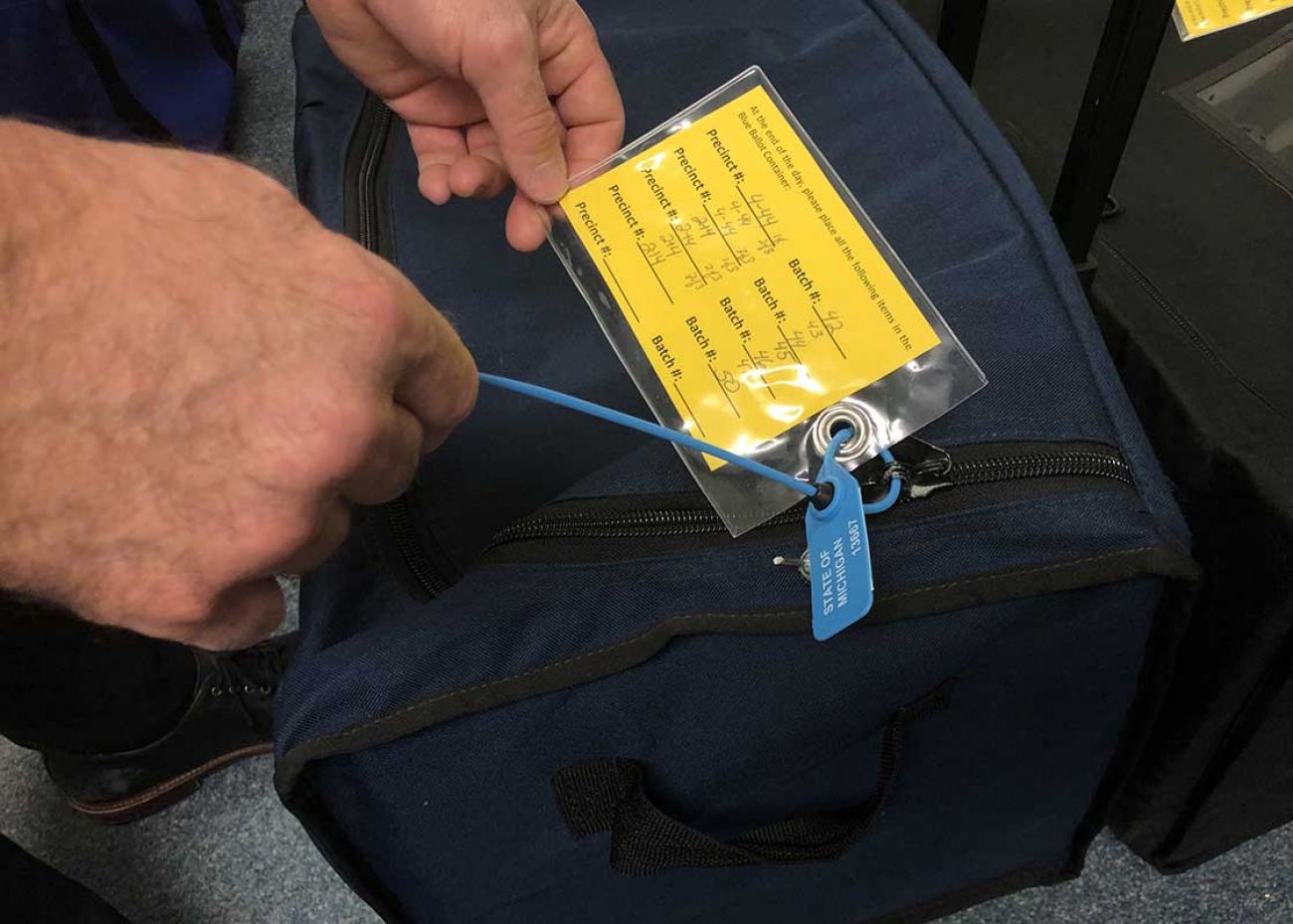

Clerks will return ballots to the same bundles of 50 and place them in sealed ballot bags overnight. The seal must be signed by election inspectors of two different political parties, and the bags can’t be opened without leaving clear evidence of potential tampering.

The bags are also certified by the Board of County Canvassers at least every four years.

Step 4: Count and process ballots

Beginning at 7 a.m. on Election Day, workers in both small and large municipalities break the seal on each ballot bag and recount all ballots inside to ensure the number of ballots in the bag matches the number written on the seal and has been logged in the clerk’s computer system.

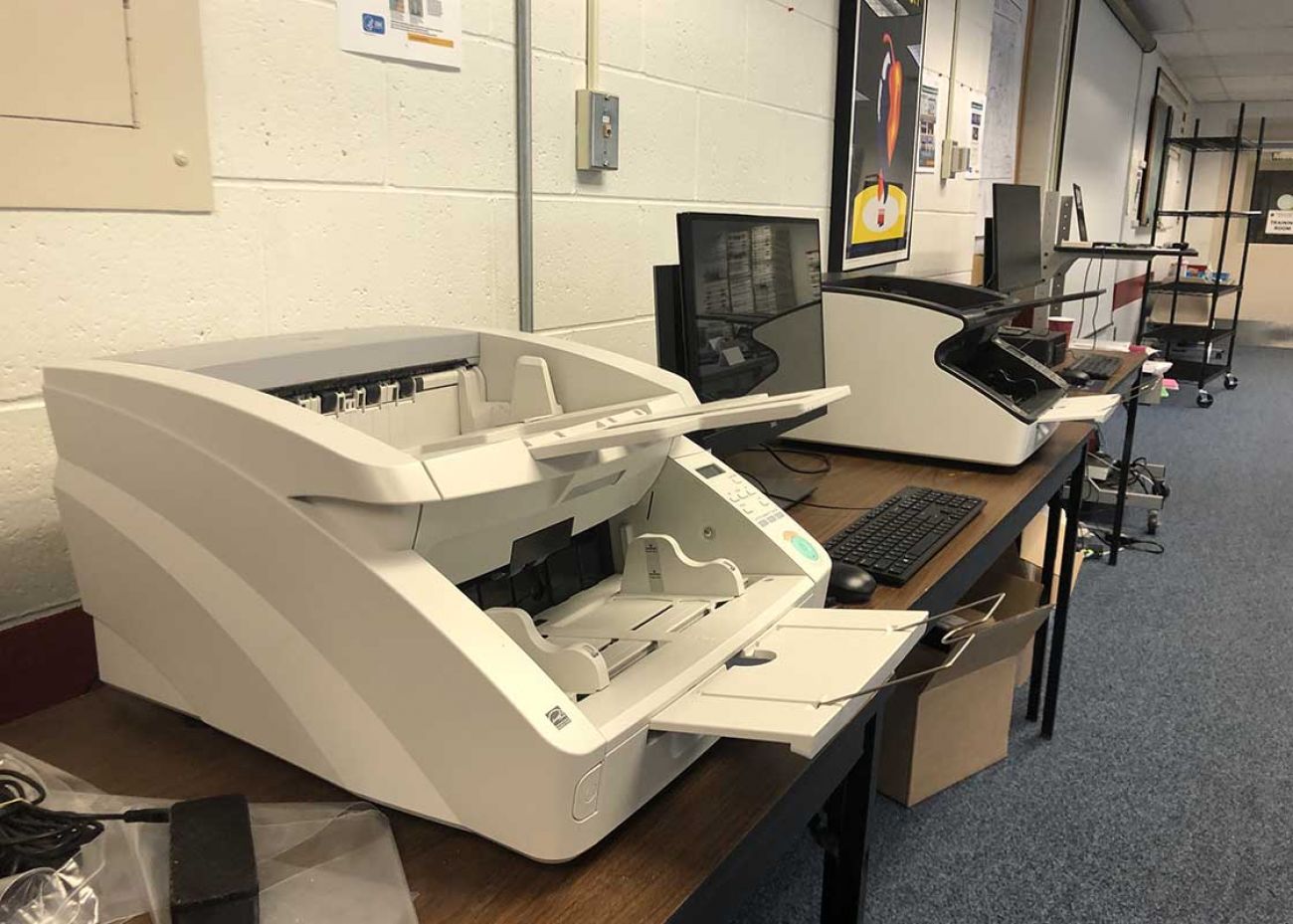

Workers rip off the stub at the end of the ballot with an ID number, take the ballot out of the secrecy sleeve, unfold it and run it through a tabulator precinct-by-precinct. The ID number stubs are stored with the secrecy sleeve to help workers double check if the ballot counts are off. Once they’re finished, the clerk’s office can report the results electronically.

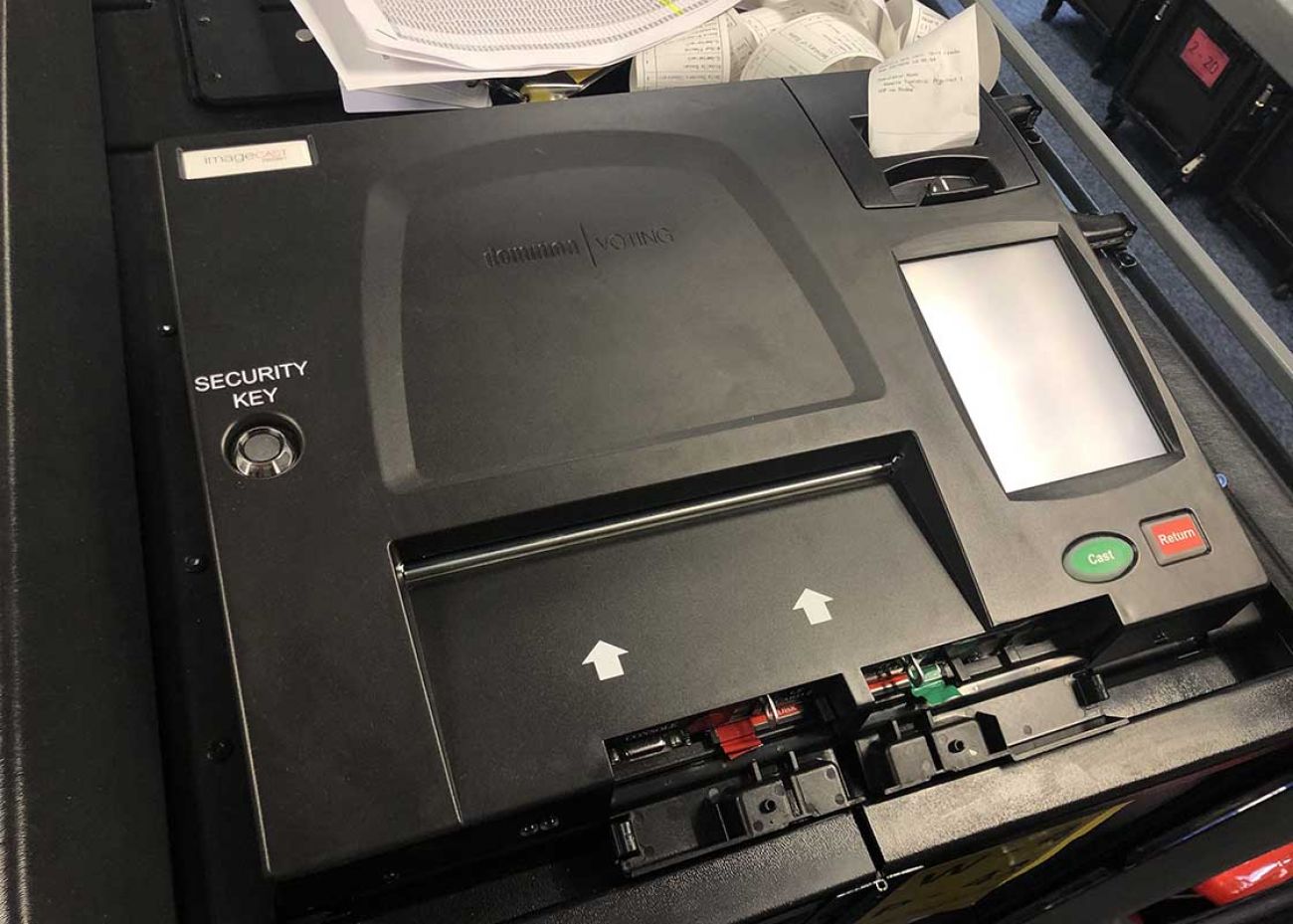

The tabulators make a full scan of the ballot. High-speed tabulators can process around 80 ballots per minute.

Ballots that have oddities — such as a bubble that’s only partially filled, a vote for too many candidates for the same office or a write-in candidate — will be electronically flagged and pop up on the attached computer. Election inspectors from both political parties work together to determine what the voter meant and log it in the clerk’s system.

Once again, the number of ballots in a precinct are checked against poll books to ensure the number of ballots are the same as the number of people who said they voted. If the count is different, election workers go through the precinct ballot-by-ballot to figure out what went wrong and record it in the poll book.

Step 5: Return to ballot bags and store

The ballots are then put back into sealed ballot bags, where they have to remain for 30 days until the Board of State Canvassers certifies the election results or until there’s a recount.

The Board of County Canvassers will review the unofficial results to make sure the number of voters matches the number of ballots cast. Any discrepancies will be reviewed by the canvassers and may require the ballots be brought before the board in a public meeting including the clerk and the precinct workers, but this is rare.

The county board has until Nov. 17 to certify election results. Then the Board of State Canvassers repeats the process and certifies election results by Nov. 23.

If someone would like a recount, the person or group must petition for the recount within 48 hours of the Board of State Canvassers signing off on election results — in that case, the canvassers most likely recount the ballots in contested jurisdictions by hand.

After the election results are certified, ballots can be removed from the official bags and put into storage bags, but they must be kept by the clerk’s office for 22 months.

In-person ballots

Step 1: Feed ballot through tabulator

After filling out the ballot, the voter feeds it into the tabulator at their polling place.

A small screen on the tabulator will indicate whether the voter made any mistakes — for example, if they voted for multiple candidates for one office. The voter will press a button indicating they’d like to cast the ballot or scrap that one and get a new one.

When the voter presses the button to cast the ballot, the vote is immediately counted. The machine keeps a total running all day and the ballot drops down into a bag inside the tabulator.

If a voter casts a vote for a write-in candidate, ballots are dropped into a separate bag so they can be checked by election workers.

If there’s a power outage, ballots are dropped into a third bag inside the machine to later be fed into the machine by election workers to be tabulated once power returns.

Step 2: Store results on SD cards and in paper reports

The votes are stored on two SD cards in the machine, which are sealed with another tamper-evident lock that can be broken only once the polls close on Election Day.

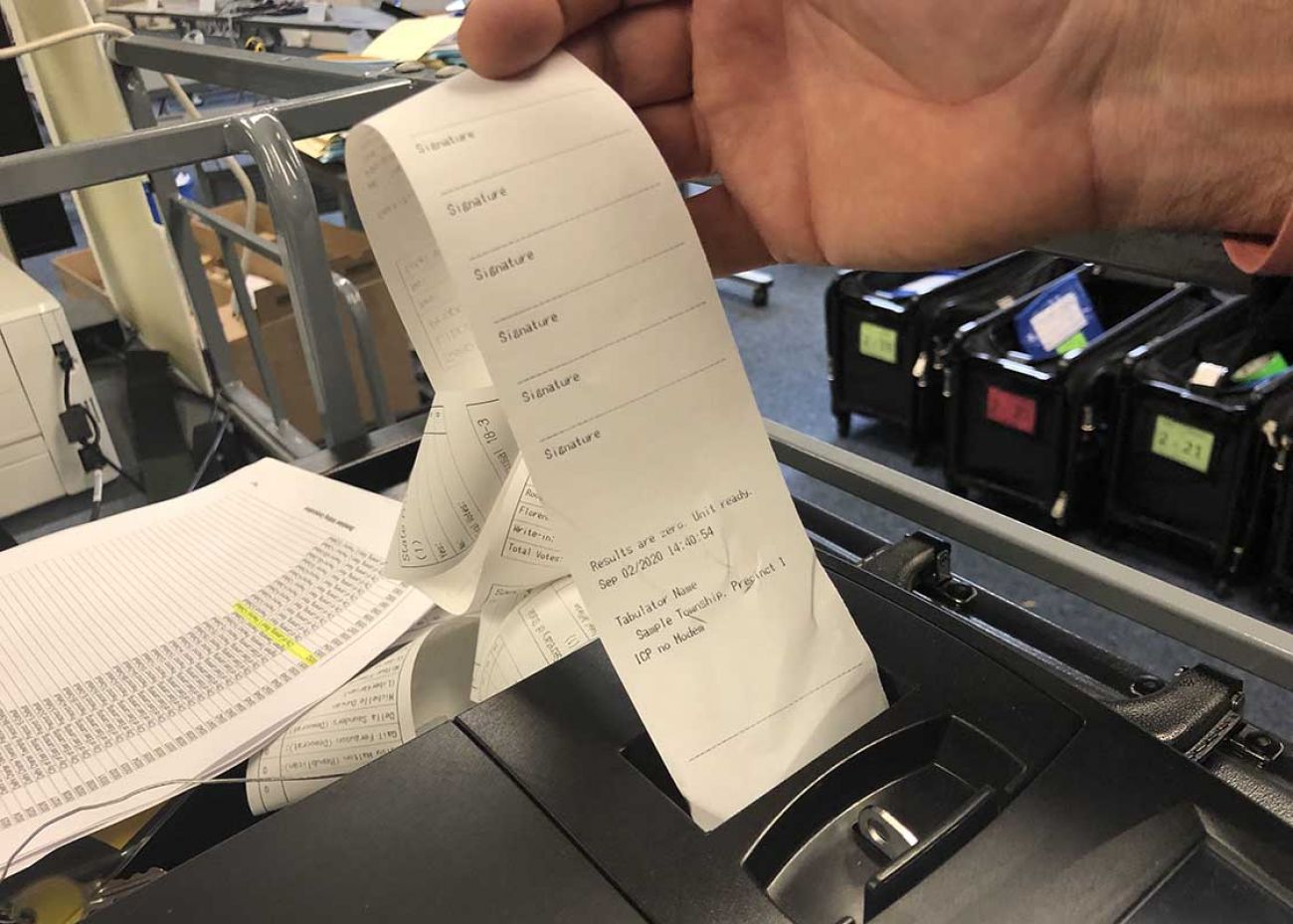

When the polls close, the chair and co-chair of the precinct (two election workers of different political parties), enter a code into the machine given to them by the city clerk that prints off three paper reports with the results.

All of the election workers who are at the precinct at the end of the night sign the paper reports.

Step 3: Transfer results to the clerk’s office

The bipartisan chair and co-chair put the SD cards in another sealed container and take them and the report to the city clerk’s office. The ballot bags, which were inside the machine gathering ballots all day, are sealed and also brought to the clerk’s office.

The chair and co-chair must ride in a car together to the clerk’s office so neither is alone with the results.

Step 4: Report results to the county

The results on the SD cards are put into the clerk’s computer system and sent to the county clerk’s office, where they’ll be reported on the county website.

One of the paper copies of the results stays with the city clerk, one goes to the Board of County Canvassers, and one goes to the county’s chief probate judge. Each will compare the paper results to the results that are uploaded to the website through the SD card to verify they’re accurate.

Step 5: Store ballots

The paper ballots, sealed in ballot bags, are stored in the clerk’s office like absentee ballots and only opened in case of a recount or in case the Board of County Canvassers asks to inspect the ballots from a precinct.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!