Deep in Trump country, a Michigan town mistrusts all elections, except its own

ADAMS TOWNSHIP — Julie Shaffer showed her ID, sat between privacy dividers, used an ink pen to fill out her ballot and fed it into a tabulator that responded with an electronic ding to indicate her vote had been counted.

Then she stepped outside and declared elections are rigged.

“They’re crooked — our government, our voting system — and I’m not really in favor of all the bullshit,” Shaffer said Tuesday outside Adams Township Hall, which is sandwiched between a cemetery and a privately-owned barn surrounded by high fences, Confederate flags and no trespassing signs.

Related:

- Trump backs loyalist for Michigan House GOP leadership post

- Michigan troopers search clerk’s office for missing election equipment

- Voting machine missing after Michigan clerk stripped of election power

- Clerk decries ‘tyranny’ after Michigan strips her of running election

“A lot of it I got off YouTube,” Shaffer said, describing her online research into the 2020 election. “I was looking for Jeff Epstein, and then I hit on all this other stuff, and I'm going like, ‘Yeah, our government’s corrupt. Our country's corrupt.’ ”

Election conspiracy theories have gripped this small town in Hillsdale County that is home to about 2,450 people and no traffic lights. More than 76 percent of local voters backed former President Donald Trump in 2020, and one year later, many continue to believe the election was rigged against him.

First-term Clerk Stephanie Scott, who has posted election and QAnon conspiracy theory content on social media, last month began to publicly question the accuracy of the township’s voting tabulator. She refused to allow routine maintenance on the machine, prompting Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson to strip the clerk of her election administration authority.

State police raided Scott’s office last week to secure part of the voting tabulator that had gone missing when county officials tasked with running the township election tried to retrieve it.

The drama spilled over to what was an otherwise uneventful local election on Tuesday in which voters approved a school operating millage renewal.

It was quiet until evening, when Scott and a handful of allies arrived at the township hall to observe as poll watchers and complained that an unlocked door may have allowed access to 2020 ballots stored in the basement in locked bags, potentially breaking the chain of custody.

Hillsdale County Deputy Clerk Abe Dane, who oversaw the election instead of Scott, told Bridge Michigan that reaching the basement requires going through three doors, the second of which is “usually locked.”

Citing what he called a "controversial atmosphere created by many false statements and misinformation regarding election security and procedures in Adams Township," Dane took the 2020 ballots, absentee ballot envelopes and applications from the township to the county office for safekeeping in a vault.

Nonetheless, hundreds of local voters still turned out to the polls on Tuesday, feeding ballots into an identical Hart Intercivic Inc. tabulator supplied by Hillsdale County Clerk Marney Kast, a Republican who has touted local election integrity but questioned “patterns” in Detroit and other large Democratic cities.

If last year’s presidential election was stolen, it probably didn’t happen here, several local voters told Bridge Michigan.

“It’s Adams Township,” Shaffer said with a laugh after casting her ballot. “How much crime do we (have) going on here? It ain’t like we're out to screw each other.”

Growing distrust

Experts say the voting machine tabulator controversy is emblematic of a growing distrust of institutions — the government, media, schools — across the United States, particularly among white, rural and Republican areas like Adams.

As of May, 65 percent of Michigan voters said they believe elections are safe and secure, according to a statewide poll conducted by Glengariff Group Inc. But the survey found that among “strong” Republicans, only 35 percent trusted elections.

"This is very narrowly an issue on the Republican side, and it's very clearly being stoked by the former president," pollster Richard Czuba told Bridge Michigan.

Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat, has called the 2020 election the most secure in Michigan history, and a Republican-led state Senate Oversight Committee investigated dozens of claims but debunked many and declared that voters should trust the 2020 results.

But Trump supporters continue to hunt for evidence in unlikely places: They’ve conducted a door-to-door canvass in Macomb County, enlisted a private investigator to grill election clerks in Barry County, and most recently attempted to preserve data on the Adams Township voting machine even though other election officials say no information is stored on tabulators.

Scott, the Adams Township clerk who has accused the state of “tyranny” for barring her from administering this week’s election, has not spoken to reporters in more than a week. She did not respond to a Bridge voicemail seeking comment on this story.

Adams Township Supervisor Mark Nichols, a Scott ally who has called 2020 “the year of the lie” and encouraged other local clerks to follow her lead, told activists this week that the embattled clerk is consulting with attorneys.

Local voters who spoke with Bridge this week offered a variety of opinions on Scott, a former Minnesota resident who won election last year for the first time in Adams Township after running unopposed for the part-time clerk position.

“I understand where she’s coming from,” said Shannon Kirkpatrick, a retiree who called himself a Trump supporter. “The last presidential election, I’m stupid enough to think that there was something wrong with it. I have my doubts about how everything was handled.”

Like Trump loyalists in other parts of the country, Hillsdale County activists are urging officials to conduct a “forensic audit” of the 2020 election, including a review of paper ballots, voter registration records and election machines.

The GOP obsession is “sad,” said Allan Rounds, a local voter who told Bridge he left the Republican Party years ago because of attacks on the Affordable Care Act health insurance law. “They’re still fighting the election from 2020.”

Scott’s critics have theories of their own. Some suspect she tried to sabotage this week’s election because she did not support the 18.2-mill school tax renewal request that asked voters to continue a tax.

“Every clerk in the county turns these machines in and gets them reset for the next election, and she held them back for some ridiculous reason,” Rounds said.

But Scott is legally required to maintain voting records for 22 months and, at least in her mind, was “protecting the integrity of her machine, which she is 100 percent responsible for,” said Tim Martin, a GOP activist who recently moved out of Adams Township but regularly films local officials as a citizen watchdog.

“I'm not telling you I'm a conspiracy theorist, but you know what, when 2 plus 2 adds up to 5, we know there's something wrong,” he said Tuesday. “And (millions of) people feel something's been wrong for almost a year now. If there's nothing to hide, why fight an investigation?”

2022 looms

On Tuesday, Hillsdale County officials took an extra step to try to assuage Scott and local voters who had concerns about the Adams Township voting tabulator: They removed the modem, which would have otherwise been activated after polls closed at 8 p.m. to quickly send unofficial results to county headquarters.

That meant it took about an hour longer than usual to post results online because Dane, the deputy clerk, had to drive a USB stick to the county office, he said.

But aside from that brief delay and whipping winds that sent him to the parking lot to chase down an errant “vote here sign,” the election went smoothly, he told Bridge Michigan.

All told, 576 out of 2,604 registered voters cast ballots on Tuesday, about 22 percent. That would be low for a presidential or gubernatorial election but is "still higher than normal" for an off-year school operating millage renewal, Dane said.

That’s relatively good news for Republicans, who will need distrustful voters to show up in 2022 if they hope to take down Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, Benson and Attorney General Dana Nessel.

But election integrity may end up being a bigger issue in primaries than the general election, said Czuba, a longtime Michigan pollster. He pointed to Republican Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin's Tuesday win in Virginia, a state Democratic President Joe Biden had carried by 10 percentage points in 2020.

"It looks to me like independents have moved on. In their mind, the Trump era is over, and they are assessing the candidates in front of them, not the candidates behind them," Czuba said.

"Republicans face a choice: They either can look forward, where independent voters are looking, or they can re-litigate 2020 and force those independent voters who rejected Donald Trump to reject them again."

In Adams Township, even some of Scott’s critics share her concerns that the 2020 election may have been compromised in some way. But several said they still voted in the local election without hesitation.

“The machine is not counting wrong — it’s what happened before they fill out the ballot,” said Janice Roberts, who criticized Scott after a post-vote lunch at Ginofli’s, the lone diner in the village of North Adams.

“Once you put it in there, the machine counts it. The fraud happened before.”

Bonnie Norris, who joined Roberts at lunch, was one of the only local residents to question Scott during a recent public meeting in which the Adams Township clerk floated the idea of ditching the tabulator to hand count ballots.

That may have violated Michigan law that calls for a “uniform voting system” through the state, and Norris worried it could void the school millage election.

“It’s ridiculous what she’s done to our township,” Norris said of Scott. “The machines are just a counter.”

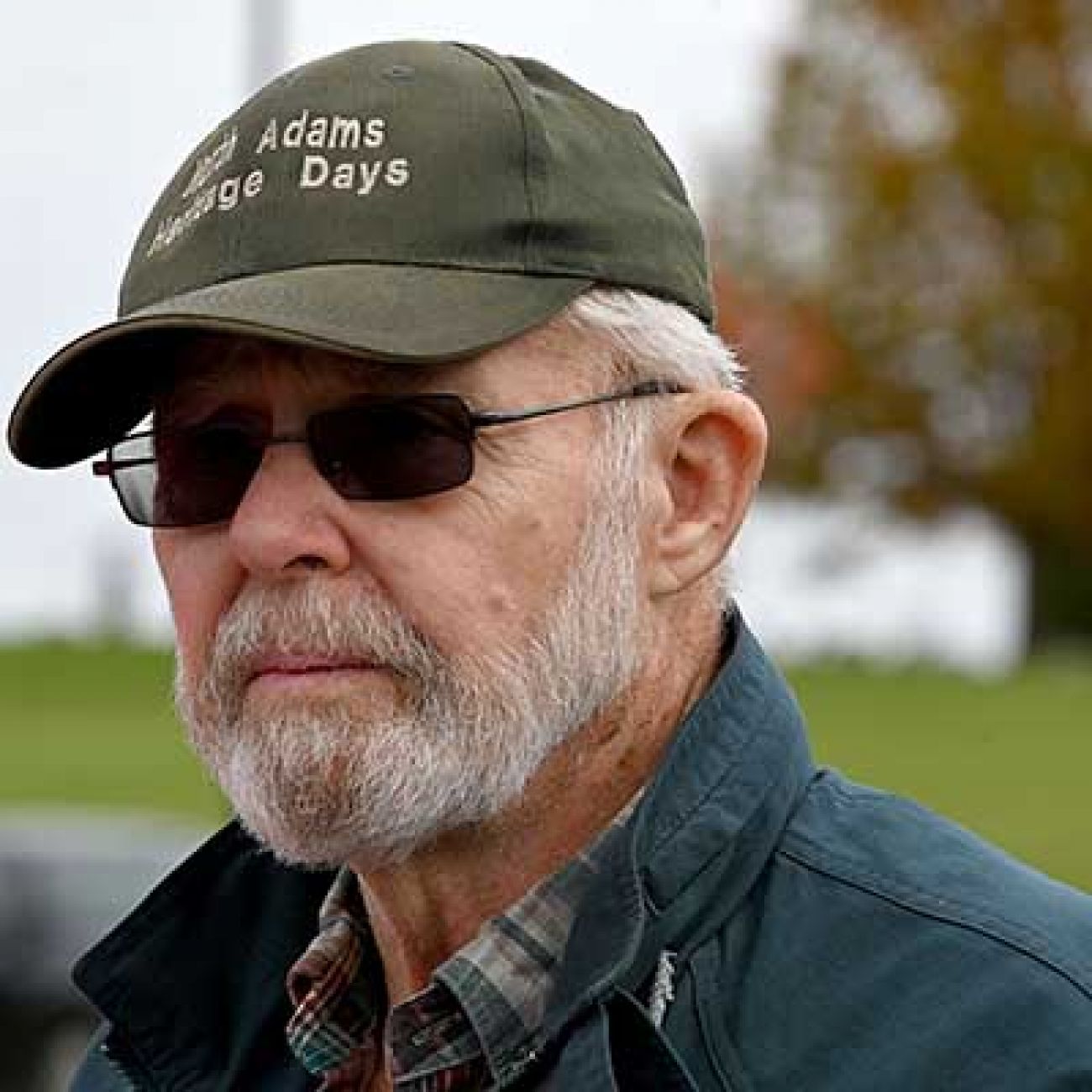

Outside Adams Township hall, Bernard McKinney lamented the local state of affairs, complaining that election fraud and COVID-19 conspiracies have proliferated in his local community over the past year.

A self-described independent, McKinney said he personally trusts elections because “there’s always a paper trail.” Michigan uses paper ballots, which are counted by a machine but can be reviewed by hand after any election.

Trump is still seen as the “second coming of Jesus” in Hillsdale County, but drive 100 miles east and the former president is considered “the antichrist,” he said.

“This country is just burning up with — I ain't gonna call it hate — but just dislike,” McKinney opined. “Trump did some good things, but he was a bully. If he'd just kept his mouth shut, they'd probably have elected him as king.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!