California is poster child for tax limitation rules, for advocates and critics alike

In the depths of the Great Depression, California lawmakers devised a bold prescription for balancing the state books.

Called Proposition 1, the 1933 measure called for a complicated shift in taxes between state and local governments and boosted state spending for schools. Almost as an afterthought, it required a two-thirds vote in each chamber to approve the state budget -- should spending rise by more than 5 percent. Voters approved it nearly 2-to-1.

In 1978, spurred by populist anger over high property taxes, California voters embraced Proposition 13. It limited property taxes and mandated a two-thirds vote for any state tax increase and for local governments seeking special tax increases.

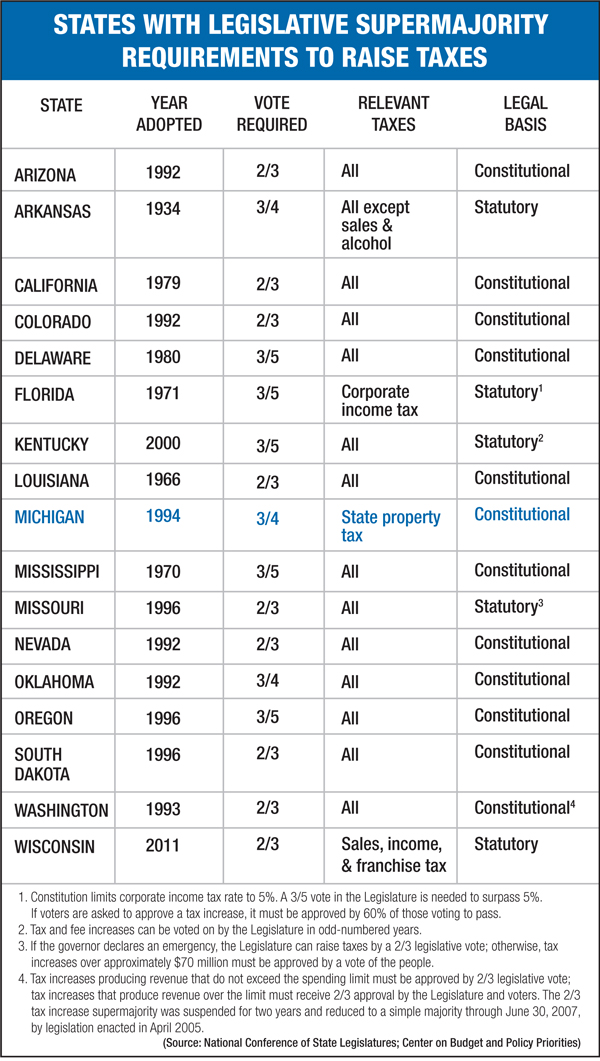

Michigan voters will address the tax limitation matter with Proposal 5, which seeks to set a two-thirds supermajority for tax increase votes in the Legislature. While the research is mixed on whether constitutional tax limitation rules ensure lower taxes, the recent history in California – and Colorado -- is fairly consistent: Mix money and supermajority rules and you can certainly expect turmoil.

The land of 2/3 votes

In the intervening years, per-pupil spending for California's K-12 education system tumbled, relative to that of other states. Public universities grappled with severe cuts in state aid. Approval of the state budget became an annual circus, as in 2009 when Controller John Chiang warned that if legislators failed to come up with a budget, he would be forced to issue IOUs to pay California's bills.

In 2010, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed a budget 100 days late.

Earlier this year, the California cities of Stockton and San Bernardino filed for bankruptcy.

There is plenty of blame to go around for California’s fiscal disarray. Californians were exuberant participants in the housing bubble, whose collapse in 2008 devastated not only homeowners, but also state and local coffers. Before that, the state budget counted on billions of dollars in capital gains taxes, inflated by the tech-sector bubble of the late 1990s. And local officials were slow to adjust budgets to rising pension burdens and other municipal expenses.

But Stanford University political science professor Bruce Cain says Proposition 1 and Proposition 13 --and their “two-thirds” handcuffs -- haven't made things any easier. Voters finally lifted the provisions of Proposition 1 in 2010, approving a measure called Proposition 25 that calls for a simple majority of legislators for budget approval.

California legislators now can pass a budget with simple majorities, but under Prop 13, still need super-majorities to pass tax increases.

“The stability of state financing has taken a real hit. We have much more volatile revenue streams,” Cain said.

Proposal 13's broad property tax cut left California heavily dependent on state sales tax and income tax. Cain noted that both of those sources are vulnerable to cyclical economic swings. And with revenues down during California's recession, legislators looked to spending targets like the state university system to make up the difference.

Cain said state funding for universities has declined from nearly one-third of their budget in the 1980s to about 10 percent.

“Our public universities are not really public anymore,” Cain said.

Research mixed on tax limits’ effects

According to analysis by Michigan's Citizens Research Council, 17 states require some sort of legislative super-majority to pass a tax increase. Proposal 5 – requiring two-thirds vote by both legislative chambers – would add Michigan to the list.

It reported no obvious correlation between super-majorities and fiscal restraint.

A 2000 study by Brown University did find that a super-majority vote requirement results in lower taxes, compared with states without the requirement. But other academic research concluded that a super-majority does not necessarily reduce total revenue, because states often raises fees and other charges to compensate for reduced tax revenues.

For all the budget turmoil in California, polls show a majority of the public still supports tax-limiting Proposition 13.

“It would do better today than when it passed, when it got 65 percent. There is an ice cube's chance in hell that it is going to be repealed,” said Kris Vosburgh, executive director of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, named for the anti-tax crusader who pushed for approval of Proposition 13.

Vosburgh rejected the notion that requiring a two-thirds vote for tax increases is poor public policy.

“In our criminal justice system, we require a unanimous vote of 12 people on a jury. What is taxation but the taking of property? Is asking for a two-thirds vote before you take someone's property really such a far-fetched idea?”

In the meantime, California has piled up an alarming level of debt.

By 2011, California's general-fund debt reached $82.6 billion, from $2.25 billion in 1978. Debt service in 2011 grew to 7.8 percent of the general fund budget, compared to 2.36 percent in 1991 and 1.47 percent in 1977.

The state's ongoing gridlock prompted legislators and special interests to turn to the ballot as a means of governance. According to the secretary of state, the state amended its constitution through initiative 69 times from 1978 to 2011.

With another looming state budget crisis, California voters will be greeted by three propositions on the November ballot to raise taxes. That includes one backed by Gov. Jerry Brown, which would raise $7 billion by increasing the sales tax and by boosting the income tax for those making more than $250,000.

“We change our constitution at the drop of a hat,” Stanford’s Cain said. “Nobody bothers to figure out if they fit together as a piece. It's very spur of the moment.”

Tracy Westen, CEO of California's Center for Governmental Studies, a nonpartisan think tank, said the two-thirds tax threshold has been “disastrous” for the state.

“My advice to Michigan would be to do anything to block it. If you are looking for stalemates and logjams, this is the perfect recipe for that.”

Ted Roelofs worked for the Grand Rapids Press for 30 years, where he covered everything from politics to social services to military affairs. He has earned numerous awards, including for work in Albania during the 1999 Kosovo refugee crisis.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!