After decades of failure, will metro Detroit pass mass transit this year?

The failed attempts to get effective regional transit in Metro Detroit can be measured in the double digits, according to Conan Smith of the suburban advocacy group Metro Matters.

By his count, 2012 legislation establishing the Regional Transit Authority of Southeast Michigan (RTA) was the 24th plan since the 1960s. The 23 previous made either some or no progress before eventually dying in Lansing, Washington, D.C., or elsewhere.

There were two iterations of DARTA, or Detroit Area Regional Transit Authority. Both were killed, one by veto pen, the other by judicial gavel. Yet another authority was plagued by governance issues and ultimately dissolved by the legislature.

Today the region has SMART, the suburban bus network, with spotty service vividly illustrated last year by the viral story of Detroit’s “walking man,” James Robertson, who like countless other lower-wage Detroiters had trouble finding transportation networks to get them to jobs, which are often in the suburbs.

Maybe the 24th time’s the charm. A lot of Detroiters, suburbanites, business owners and other advocates for a true regional transportation system hope it is.

Public transit hasn’t had an easy time of it in southeast Michigan, not since the social changes of the past century dovetailed to drive commuters off buses, streetcars and trains and onto freeways, nearly all in privately owned cars. The reasons for mass transit’s failure in metro Detroit are numerous, but can be sorted into two categories familiar to local residents – poor relations between cities and suburbs, and concerns over costs, mainly.

Sometime in the upcoming months, the RTA will issue a new master plan to develop and coordinate public transit in the four-county area it encompasses – Wayne, Oakland, Macomb and Washtenaw. Although details are still under wraps, it will include bus rapid transit lines running on spoke-like routes from downtown Detroit along Woodward, Gratiot and Michigan Avenues, as well as enhanced service on some crosstown routes as well. Buses from the Detroit Department of Transportation and SMART will carry riders between those trunk lines. A link between Detroit and Ann Arbor is also anticipated.

And there will be a millage proposal, a property tax increase for the four-county region, to pay for all of it. No amount has been set yet, but most expect it will be around 1 mill, or $1 for every $1,000 of state equalized value (50 percent of market rate), which if passed would raise, in the four-county area, about $150 million, said Smith, enough to trigger additional federal funds and go a long way toward jump-starting the region’s belated transit plan.

“Yes, there’s reason to be hopeful, thank god,” said Smith. But it took “a lot of stars aligning to get us the governance structure we need.”

That, he said, is what doomed public transit the first 23 times: A failure to get public officials in the city and suburbs to align their interests in a mutually agreeable way. The current RTA stands on more solid ground, crafted to distribute funding as equitably as possible among the four counties while still recognizing that the urban core of Detroit has the most need of immediate investment.

As for those aligning stars, they include:

Detroit’s recovery. The city’s successful exit from municipal bankruptcy left behind a cloud of optimism, tempered with the realization that without access to employment opportunities for Detroit residents, many of them low-skilled, there will be no significant recovery for the city. Detroit’s spotty bus service has been upgraded post-bankruptcy, but still, most Detroit residents’ jobs are outside the city, and a quarter of its residents do not own cars. To get to work, residents need reliable public transit.

Generational shifts. Younger people nationwide are voting with their feet, moving into city centers and using the transportation mix more densely populated urban cores require, one where cars are only one available mode, along with buses, light rail, ride sharing and bicycles. Better-educated young people, the future of an increasingly knowledge-based workforce, are looking for robust transit as they look for jobs. At the same time, older baby boomers are retiring and opting to “age in place,” i.e., in their own homes, for as long as possible. They recognize they will likely not be able to drive in their final years, and want reliable transportation to shopping, doctors and other destinations.

Environmental concerns. The drive to lower carbon emissions and greenhouse gases now has an international agreement behind it, and general awareness is high enough that some are opting for electric cars and changing behavior to reduce their own environmental impact. Using mass transit is part of that strategy.

Work technology. Commuting is dead time behind the wheel of a car, but a transit commuter on a wifi-enabled bus, or even with the ability to create their own mobile hotspot with a cell phone, can get work done on the ride.

All of these are ticked off by Paul Hillegonds and Michael Ford, chairman of the RTA board and its CEO, respectively, as they discuss the future of transit in southeast Michigan. Ford was lured to Detroit from Ann Arbor, where he helped expand that city’s system to include Ypsilanti and Ypsilanti Township, and previously worked for the Portland, Ore., transit system. Hillegonds is a former speaker of the state House of Representatives, led Detroit Renaissance (the predecessor to Business Leaders for Michigan) and now works as head of government relations for DTE Energy.

Hillegonds points to a Brookings study that says the Detroit metro region has one of the longest median job commutes in the country among major metro areas.

“And the current transit system doesn’t make it easy,” he said.

Many transit riders could testify to that.

More coverage: In Cleveland they built it and riders came, along with a whole lot more

Megan Owens, executive director of Transportation Riders United, rides the bus to her downtown office from her home in Hazel Park. But the bus runs only every 45 minutes and, if she misses a connection at the old state fairgrounds transit center, she can find herself facing an hour-long wait, as she did one bitterly cold morning last February.

Owens has options, though. She called her husband to pick her up. Most riders don’t.

Daniel Spyker is 63, disabled but “high functioning,” and likes to get around by bicycle as much as possible. When he needs to come downtown, he can put his bike on a rack and make the trip from southwest Detroit fairly easily. But when there are breakdowns or vehicle shortages on the Michigan Avenue route he usually takes, “I could have a two- or three-hour wait.”

For employers like Jackie Victor, CEO of Avalon Bakery, in Detroit, better transit is something she wants for both the city and her workforce of 65, spread across three locations.

“For every reason on the planet, (improved transit) would make our employees’ lives better,” she said. “And it makes for a more vibrant and diverse metropolitan area. If everyone’s taking public transit because it’s available, not because it’s the last resort, you have a different mix of people. A car is such a huge economic drain in Detroit, especially for poorer people. For what middle to low-range (earners) make, a lot would probably rather not have a car.”

At public meetings the RTA has been holding throughout the region to gain input, stories like this are being shared, and people are enthused about this idea of finally getting more robust service throughout the region, Ford said. “They want to see something happen, even if they don’t use it themselves.”

And among the 4.2 million residents of the four-county area, most still probably won’t use a new system. But the state law establishing the RTA requires that, should a tax be passed, 85 percent of monies collected must be spent in the county from which it came. There’s also a no-opt-out provision; one major criticism of the current SMART system is that individual communities can opt out of the system, leading to vast holes in service. Under the RTA, that would be disallowed.

The idea behind the 85-percent rule is to make sure that while every community in the area won’t get bus rapid transit, all will get something, Ford said, including “paratransit,” in smaller vehicles that travel into neighborhoods, transporting the elderly and disabled on door-to-door trips.

Taking a region to transit school

Southeast Michigan is not only the center of the domestic auto industry, it’s a place that grew hand-in-glove with cars and the freedom they offer. And for most commuters, cars work just fine. So a big part of the RTA’s work will be to convince voters that the area still needs effective public transit.

In that task, they’ll have the help of the Kresge Foundation and the Detroit Regional Chamber, which plans an educational campaign sometime between the announcement of the master plan this spring and the millage vote in November. Because of its nonprofit status and mission, the foundation won’t be advocating for a particular vote, or even the master plan. But the public needs to be informed of what the lack of an effective system does, and doesn’t do, for the region, said Laura Trudeau, managing director of community development and Detroit at the Kresge Foundation.

“We’re losing our young people to other regions with better mass transit,” Trudeau said. The foundation has recognized the region’s transit challenges for a decade, and of the 30 largest cities in the U.S., Detroit has the least capacity and dollars spent, she said.

Moving large numbers of people around via buses and trains is “better for the (city’s) core, better for the environment. (And) there are other people who don’t want to spend as much time commuting (by car),” Trudeau said. “There’s a shift going on now, and we can capture some of that momentum.”

But the largest issue, according to Trudeau, remains an unnecessarily burdened workforce in the city of Detroit, who find getting to their jobs outside the city expensive, stressful or even impossible.

“The disconnect between jobs and people, where they live, is a problem,” Trudeau said.

Cassandra, or a realist?

Gerald Poisson doesn’t want to be the fly in the ointment.

He said the region could benefit from a beefed-up system, including Oakland County, where he has served 11 years as deputy to County Executive L. Brooks Patterson, a longtime critic of some regional transit plans as too expensive and not much use to Oakland County residents.

The county administration, Poisson said, has been supportive of realistic, cost-effective plans for years. But in Oakland County, fiscal prudence is a mantra, and remember those aligning stars? Not all of them are bright and twinkly, he suggested.

“We have to factor in the Detroit Public Schools and Flint (water) disaster,” he said, twin crises requiring state attention for resolution. “I don’t see how those are going to be solved with anything other than a lot of money, and I’m afraid a lot of (voters) will see a lot of (taxpayer money being spent on those emergencies), and it will be a huge challenge to get them to approve more.”

Poisson said he’s hearing of a possible millage request of at least 1 mill, maybe 1.1, and “in Oakland County, 1.1 mill is $57 million at current value. In Detroit, it’s $7.7 million. Think of the public education it will take to show folks how that can be distributed in a fair manner.”

The 85-percent return rule may ameliorate some of those concerns, but Oakland County is a big, diverse place. Bus rapid transit will undoubtedly be welcome in the more densely populated, southern parts of the county, where residents are more likely to work and play in Detroit, but “northern Oakland will say, ‘What are you going to do for me?’,” Poisson said. “Those subdivisions are not laid out for public transit. Some have no sidewalks.”

Interurban rail, too

Former Battle Creek mayor, state senator and U.S. representative Joe Schwarz puts it this way: “The wise and appropriate and correct public servant, when faced with (constituent concerns about public investment), tells them we have to do it.” Schwarz isn’t in office any more, so he can say that. But he also advised the governor’s office on railroads for a while, and helped with the state’s 2011 purchase of roughly 145 miles of rail line between Kalamazoo and Dearborn. That’s the same line that many hope will eventually carry passengers from Ann Arbor to Detroit on an RTA train, perhaps as many as three or more a day.

Schwarz said rail travel could be easily restarted between the two cities, and should.

He said “55-60,000 people commute into Ann Arbor (for work), and 30-some thousand commute out. You can take a lot of people off the roads if you make train travel more attractive.”

It’s all a tall order, but if it manages to come off, the region will be better off, said Elisabeth Gerber, an RTA board member and expert on transit policy at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. (Gerber also serves on the steering committee for nonprofit The Center for Michigan, which runs Bridge.)

“For cities, even if you are not likely to use expanded transit, it’s valuable to our communities,” she said. “It helps people get to work, and it’s a huge economic growth factor. People who benefit directly are only one step away from those who use it.” Whether the time is right is an open question, but if it isn’t right this year, under the RTA law, it’ll be two more before the RTA can propose an alternative.

The future arrives on schedule

Say the millage request is cursed by bad timing, and fails. What then? Gerber admits there is “no plan B.” The status quo would have to do, while the way people get around would continue to evolve, maybe not here, but elsewhere.

Susan Zielinski is managing director of an entity also known as SMART, this one at the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute. That acronym has nothing to do with the suburban bus system, but stands for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility Research and Transformation, informally known as “mobility management.” Zielinski studies the way people get around urban environments around the world, and it’s a lot more complicated than a choice of cars or buses.

Today’s urban-core resident is “multi-modal,” traveling, in the course of a day, by bus or train, bicycle, cars or their own two feet. Short-term car rentals like Zipcar, ride-sharing via Uber or Lyft, and bike-sharing services all play a part. Smartphone apps with GPS make trip-planning seamless, and “it all becomes one system, the way your phone, your laptop and your printer all talk to one another,” said Zielinski.

Privately owned cars are still very much a part of this, but a lesser part. And as the world’s economy continues to coalesce around urban areas, these transportation alternatives have to be considered as cities look to attract talent, Zielinski.

If Detroit passes on stepping up regional mass transit, Zielinski said, “Detroit is amazing at the moment. The kinds of things getting under way there, we haven’t seen in 10 years.”

But new modes will continue to be demanded by riders, she said, and there will be missed opportunities.

“All the good things (will) happen slower.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Woodward Avenue pavement has been torn up for nearly two years as rail is laid for the M-1 Rail commuter line from Campus Martius Park to the New Center area. (Photo by Sean Marshall via Flickr; used under Creative Commons license)

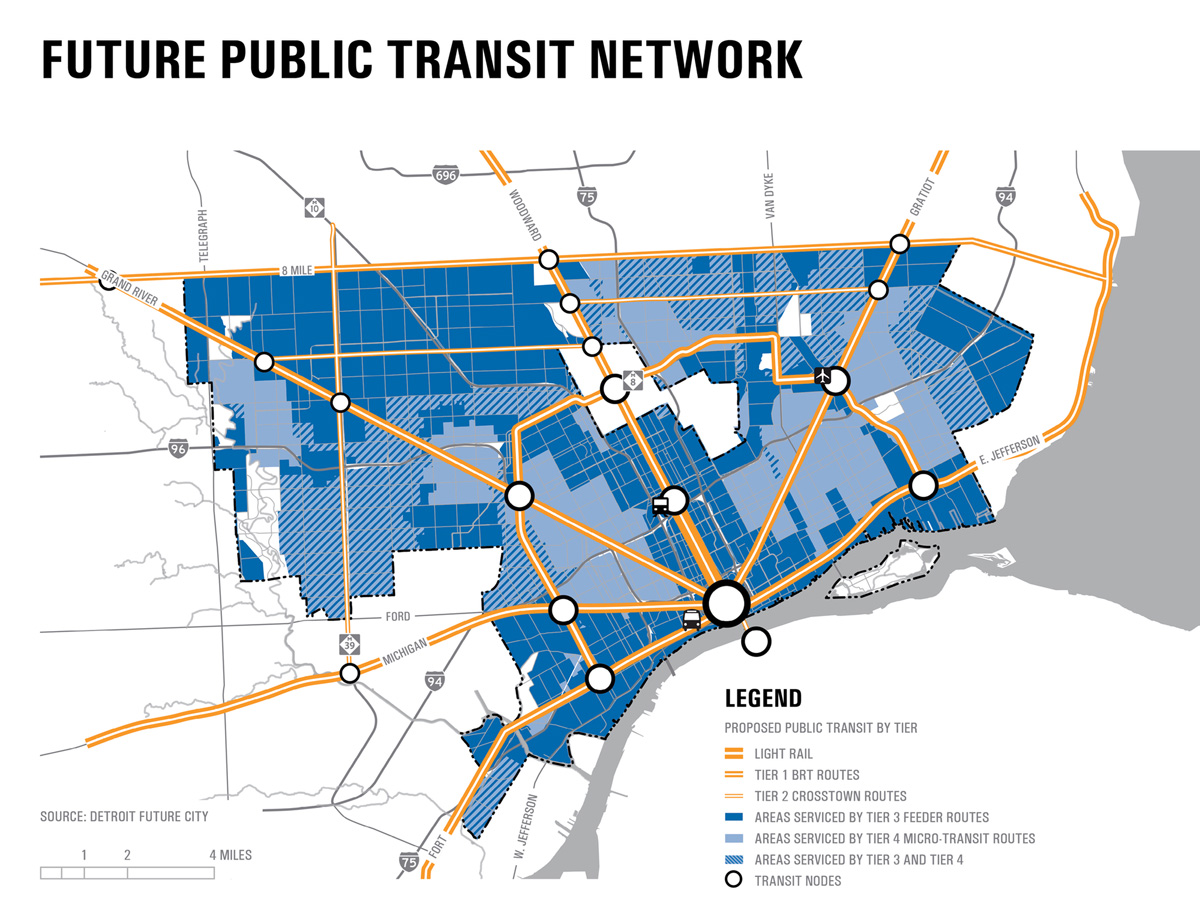

Woodward Avenue pavement has been torn up for nearly two years as rail is laid for the M-1 Rail commuter line from Campus Martius Park to the New Center area. (Photo by Sean Marshall via Flickr; used under Creative Commons license) The nonprofit Detroit Future City envisions a 2030 regional transit system that includes bus and light rail service on main arteries and connectors. (Courtesy Detroit Future City)

The nonprofit Detroit Future City envisions a 2030 regional transit system that includes bus and light rail service on main arteries and connectors. (Courtesy Detroit Future City) Michael Ford is CEO of the Southeast Michigan Regional Transit Authority (Courtesy photo)

Michael Ford is CEO of the Southeast Michigan Regional Transit Authority (Courtesy photo)