11,000 Michigan families confront the unknown

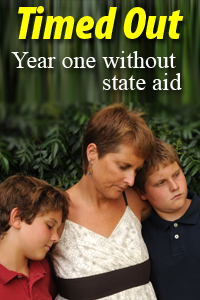

The roles Sharon Matthews has fielded so far are hardly the stuff of cakewalks: high school dropout; single mom; gunshot victim.

But her toughest role yet begins next month: Guinea pig.

The 41-year-old Detroit resident and her 15-year-old daughter are among the 11,000 Michigan families banned from welfare, as the state of Michigan begins to enforce a 48-month lifetime cap on cash assistance.

Matthews knows her benefits likely will disappear forever in November. What she and others, from the office of Gov. Rick Snyder down to local soup kitchens, don’t know is what will happen after that.

The changes wrought to Michigan's welfare system by Snyder and the Michigan Legislature are unprecedented nationally. No other state has kicked so many people off assistance in such a short amount of time, with such little notice. The result is a volatile social experiment that could help transform the state’s economy, or fill the beds of homeless shelters and prisons.

Over the next 12 months, Bridge Magazine and Michigan Radio will report on the results of that experiment. We’ll chronicle the lives of families as they adjust to life off welfare, and assess the economic impact of reform on state government and nonprofit charities.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen to me,” said Matthews.

Neither does anyone else.

Big changes, small bucks

Welfare reform isn’t just about the state shaving a few bucks out of the budget (the annual savings work out to less than $7 per Michigan resident). There are starkly different views between Republicans and Democrats on the role of government in helping the poor.

The Family Independence Program, run by the Michigan Department of Human Services but funded primarily with federal dollars, provides cash monthly to low-income families with minor children, as well as to pregnant women. The payment to a family of three, for example, is $492 a month. InMichigan, a family of three must make less than $815 a month (less than $10,000 a year) to qualify for help. (Families receiving FIP aid almost always are eligible for other assistance programs, such as food stamps, which remain in place.)

About 79,790 Michigan families were on FIP in September. Among those, 11,162 families (with about 30,000 kids) will be removed in November, the vast majority being Michigan’s chronic, urban poor.

(Cuts don't fall evenly across Michigan)

Backers of the changes say only two states now operate without a lifetime cap (an Urban League report lists three: Vermont, Maine and Washington). Michigan already had a 48-month cap on the books, but has not previously enforced it. Like Michigan did previously, other states leave “wiggle room” to allow many recipients to stay on the dole long after they reach the cap.

For example, one study found that, in 2005, about 52 percent of the federal caseload was theoretically subject to a welfare time limit, but less than 3 percent were actually timed out. Other Midwestern states have "soft" caps of 60 months (Indiana cuts off adults at 24 months, but kids in the family still receive cash assistance).

“To me, what makes the new Michigan law particularly egregious is that it counts months retroactively, so that families are being immediately cut off,” said Luke Shaefer, assistant professor of social work at the University of Michigan. “To my understanding, this is unprecedented. These were families who thought they were ‘playing by the rules,’ many of them engaging in their work requirements.”

That’s not how backers of the revisions see it.

“We have a temporary assistance program that has become a permanent benefit for too many people,” said Ari Adler, spokesman for House Speaker Jase Bolger, R-Marshall. In fact, the federal block grant that funds FIP in Michigan is called "Temporary Assistance for Needy Families."

Adler added, “People get trapped in the system. You have to break that cycle.”

Get a job

To Snyder, the solution for Matthews and others banned from FIP is simple: Get a job.

About 30 percent of the families losing benefits have been on welfare for 10 years or more. “(They) need to be working,” Adler said.

Will Michigan’s chronic poor move seamlessly from welfare to work? That’s what happened in the mid-1990s, when national welfare reform went into effect. The number of families on cash assistance nationally is less than a third of the number in 1996, when reform took effect, with many getting jobs, according to research by Sandra K. Danziger, professor of social work at the University of Michigan.

But that was during an economic upswing.

Today, Michigan has an 11.2 percent unemployment rate, and many of those job-seekers have more experience and education than those who have received cash assistance for more than four years. The average time for a jobless person in Michigan to find a job is 53 to 99 weeks.

Many of the soon-to-be ex-recipients already have part-time jobs or are enrolled in some kind of job training program – a requirement of the program, said Melissa Smith, senior policy analyst for the advocacy group Michigan League of Human Services.

Makeda Taylor, 33, of Detroit, worked as a school cook until she was laid off this summer. Now, she walks to the library to look on the Internet for job openings. “It’s true, I do need to get out and get a job,”Taylor said. “But what if there are no jobs or you have to go through training? I’ve done tried every job and nobody calls me back for an interview or nothing.”

Tamika Thomas is attending Wayne County Community College to become a radiology technician, using her cash assistance from FIP to pay rent and utilities while she tries to make a better life for her four children. When she loses her benefits next month, the 33-year-old Detroiter will have to stop taking classes and get any job she can.

“I’m supposed to be in class today,” Thomas said on a recent Tuesday. “But I’m on my way to a tomato (canning factory) that I heard was hiring.

“If I don’t get a job, I’m going to end up in a shelter,” Thomas said.

Many of the chronic poor have physical, mental or educational challenges that make holding jobs more of a struggle, said Gilda Jacobs, president of the Michigan League for Human Services. “Some are functionally illiterate,” Jacobs said. “Some have transportation barriers. Some have child-care barriers.” Cutting them off assistance will not make them more employable, Jacobs said.

The Rev. Michael Brown of the Kalamazoo Gospel Mission homeless shelter, however, believes some welfare recipients could use a kick-start. “(Cash assistance) is not a help net, it’s a way of life for some people,” said Brown, whose homeless shelter averages 230 people per night. “It will take some time to turn people around to thinking about personal responsibility.”

Just how people survive while they’re turning things around is what worries some organizations that work with the poor.

Scott Dzurka, president of Michigan Association of United Ways, fears a vast increase in homelessness next spring.

The Department of Human Services is offering three months of emergency rental assistance for those being cut off from welfare. After that, “it takes a few months for people to be evicted,” Dzurka said. “People will stay with family and friends until their welcome wears out.”

Where the money is

Based on an average benefit check of $509 per month for each of the 11,162 removed families, the state stands to save about $68 million, but some of those savings could be consumed by costs caused by the revisions.

Crime likely will go up, as some people take desperate measures to feed their children or keep a roof over their heads, said Christopher Maxwell, criminal justice professor and associate dean of the College of Social Sciences at Michigan State University. “People will essentially transition from one public roll to another … shifting (the financial burden) from one agency to another in the budget,” Maxwell said. “The question is, which is more costly, welfare or prison?” (Taxpayers will save about $6,100 for each family kicked off cash assistance; the cost of housing an average prisoner in Michigan is $28,743.)

For fiscal 2012, the Department of Human Services received $1.2 billion in state funds, and will spend an additional $5.6 billion in federal money.

Meanwhile, leaders at food banks and homeless shelters are worried that they may be stretched beyond their resources by the families banned from state help. “I’ve already seen a huge increase in people coming in (to the shelter) with no income,” said Angie Mayeaux, executive director of Haven House inLansing. “I don’t want to cry wolf and say the world’s going to end. These people are survivors. But there are a lot of people on the edge.”

Some families are moving in together to save money, while others are splitting up.

Bonnie Baker, 26, of Jackson, sent her son to live with her brother in Northern Michigan in anticipation of not having enough money when her assistance is cut off next month.

Jerry Buchanan, 52, of Grand Rapids, said he worries his 12-year-old daughter “will end up in foster care and I’ll end up on the streets.

“What’s going to happen when the shelter is full?” Buchanan asked.

“When this legislation was being discussed, there was little thought about what would happen to these people,” said Robert McCann, spokesman for the Michigan Senate Democratic Caucus. “In times of economic downturn, it’s not the time to push people into the unknown.”

DHS will try to track the timed-out families, using databases from other programs, such as food stamps, to see how the families fare in the year after they lose benefits, said DHS spokeswoman Colleen Rosso.

No one is more eager to learn the results of this experiment than Buchanan and the other 11,000 families about to lose benefits.

“They say people will survive,” Buchanan said. “But they may not like the way we survive.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!