Moving from ‘we had money’ to ‘they want money I don’t have’

GREENVILLE – The line began forming an hour before the food truck arrived, starting in the parking lot next to the barren acreage where once stood the nation’s largest refrigerator factory and winding around the front of the former UAW hall. Men and women, some with children, held empty boxes and laundry baskets they soon would fill with free produce, bottles of orange juice and loaves of bread, a scene reminiscent of Depression-era bread lines.

While there are hopeful signs that the economy is recovering -- including rising corporate profits, a booming stock market and a declining unemployment rate -- many who once considered themselves solidly middle class are struggling to hang in there, or even have slipped beneath the poverty line.

Several waiting in the Greenville line said they lost their homes after Electrolux closed its Frigidaire plant in 2006. Many lost hope of ever recovering the economic status they once enjoyed. One said she had attempted suicide.

Officially, Michigan’s unemployment rate stood at 8.4 percent in April, way down from 14.2 percent in August 2009.

But -- “I’m starting to not put much credence in the unemployment rate,” said George Erickcek, an economist and senior regional analyst with the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo.

Michigan’s work-force participation rate (the percentage of working age adults who are employed or actively seeking jobs) dropped from 65 percent in 2005 to 61 percent in 2011, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That means that thousands of the state’s unemployed simply gave up looking, Erickcek said.

“One of the questions I’m struggling with is, what are these people doing who are not part of the work force?” he said.

Many of those in the food line have exhausted their unemployment benefits. One woman said her husband’s unemployment compensation was reduced 11 percent as part of the federal sequestration cuts imposed when Congress and President Obama failed to agree on a deficit reduction plan.

“Let’s face it: the economy is messed up,” said Bob LaBonville, waiting in line with his girlfriend Rose Zerbst, who worked 27 years at the plant until it closed. “Our government is messed up. The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer. This is America? Come on.”

His assessment is not far from what economists see when they look further into the numbers.

“There was a time when the middle class in Michigan was the envy of the rest of the nation,” said Charles Ballard, a Michigan State University professor of economics. “That’s no longer so.”

Thirty or forty years ago, a high school diploma and a job building autos, office furniture or refrigerators were enough to assure workers permanent membership in the middle class.

“We had this phenomenon where there were hundreds of thousands of people working in factories, and they had a house with a two-car garage and a boat and a cottage at the lake,” Ballard said. “Manufacturing was what drove it, and autos more than anything else, but the share of our economy that’s attributable to manufacturing went way down.”

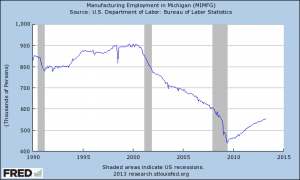

As recently as January 2000, Michigan boasted 906,500 manufacturing jobs, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. By April, it had dropped to 553,700. Construction saw a similar decline from nearly 212,000 jobs in August of 2000 to 125,000 in April of this year.

“It was a horrendous fall,” Ballard said, yet it is an over-simplification to say Michigan’s entire middle class is struggling. In Oakland County, average annual per capita income ($36,314) is twice as high as in Luce County ($18,294), according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

MORE COVERAGE: So you think you are a member of the middle class?

Montcalm County, former home of the Greenville refrigerator plant, often vies for the state’s poorest county, with a per capita income of $19,010, and a poverty rate of 19.6 percent. Prior to 2000, Michigan’s poverty rate was consistently below the national average. In 1998, 10.2 percent of the state’s residents were living in poverty. By 2011, the state’s rate had climbed to 15.7 percent compared to the national average of 14.3 percent.

Much of the decline in personal income in recent decades is due to what Ballard called the “education gap.” On average, a worker with a bachelor's degree earned about $26,000 more each year than a worker with a high school diploma, the Census Bureau reported in 2009.

As a result of Michigan’s historic reliance on manufacturing, “we developed a culture that didn’t put a whole lot of emphasis on post-high school education,” Ballard said, and the outcome is lower wages and expectations for those once considered middle class. The percentage of Michigan residents over age 25 with a bachelor’s degree or higher (25.3 percent) is lower than the national average of 28.2 percent.

Ballard pointed to the assembly plant General Motors opened in 2006 in Delta Township near Lansing, where “there are a lot fewer people around and a lot more robots and computers. The technological change has been a challenge for people who do simple, repetitive tasks.”

Outsourcing of manufacturing to Mexico, China and other countries, where wages are much lower, also has contributed to the decline of Michigan’s middle class. That’s what happened when Electrolux closed its Greenville plant in 2006, moving manufacturing to Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, and idling nearly 3,000 workers.

Most of the adults waiting in the food line once held what used to be called “good jobs” in that refrigerator plant, the kind that assured them a livable wage and a ticket to the middle class. Many still consider themselves members of that nebulous group, although by most standards, they are not.

Stan Soules Jr. says he is middle class, although his $10-an-hour factory job and $20,000 annual income places his family of five well below the federal government’s poverty line of $27,570. He was laid off three months last year. “It’s tough,” he said. “It would be nice to be making more money, so you don’t have to tell the kids, ‘no’ when they want a new shirt or new pants or new shoes.”

They get by partly because his wife, Jennifer, buys groceries with a state-issued Bridge Card, makes regular rounds of four area food pantries and stands in line when the Feeding America West Michigan Food Bank truck makes its monthly visit to Greenville. She was laid off from her job at another Greenville factory, Clarion Technologies, in 2008.

“I think we’re lower middle class,” she said, preparing dinner for the young couple and their three children. The tomatoes in the spaghetti sauce she got from the food truck. Likewise the lemons for the lemonade. The spaghetti came from a nearby food pantry.

“We do pasta and beans, so we don’t need a lot of meat,” she said. “I mean, we’re not struggling as bad as some people are. If you budget, you can do it, but it’s a struggle.”

Their home, a former Danish Brotherhood hall in the small town of Sidney, was in serious disrepair when they bought it from her father and began making it livable.

Not many miles away, a storm blew through, taking with it many shingles from the home where Edith and Phillip Flowers are raising four of their grandchildren, ages 4 to 19. A tarp covered a part of the roof where an earlier storm had peeled off more shingles. There is no money for repairs, and the couple cannot afford homeowner insurance.

In 2000, certain their place in the middle class was secure, the couple built a new home in Greenville. Phillip worked for a foundry in Belding, and Edith assembled refrigerators at Electrolux.

“It was a good job,” she said. “A lot of people raised their families when they worked there. We had money. If we wanted to go somewhere, we could. We had nice vehicles. We didn’t have to worry about nothing.”

Then Phillip injured his back and went on disability, and, in 2006, after 28 years working for Electrolux, Edith lost her job when the plant closed.

The following year, they lost their home to foreclosure and moved into their current home, an old house in rural Montcalm County, where Phillip’s late mother had lived. Their only income for the family of six is $1,300 a month from his pension and Social Security disability.

The couple, both in their 50s, worry constantly about paying their bills and are afraid to answer the phone, since it often is a bill collector.

“We can’t do anything about it anyway,” Phillip said. “They want money I don’t have.”

Their oldest granddaughter, Kasey, graduated high school a year ago, but hasn’t yet found a job, although she conceded she’s done little beyond calling around. Children raised in poverty often develop a sense of limited possibilities, psychologists say, and simply give up.

“Hopefully, when these children get old enough, there’ll be something there for them,” Edith said. “I just don’t know.”

Her husband doubts it.

“Right now, it just don’t feel like it can get any better,” he said. “We’re in a hole, and we can’t climb out. I never thought we’d be here. We had a good income when I was working and she was working. We were making close to $50,000 a year. I thought we were doing pretty well, then we got shot down to this.”

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Stan and Jennifer Soules share dinner with their three children in their home near Greenville. Since both Stan and Jennifer were laid off from factory jobs, the family meals revolve around pasta and beans, Jennifer said. Still, the family considers itself middle class. (Bridge photo/Lance Wynn)

Stan and Jennifer Soules share dinner with their three children in their home near Greenville. Since both Stan and Jennifer were laid off from factory jobs, the family meals revolve around pasta and beans, Jennifer said. Still, the family considers itself middle class. (Bridge photo/Lance Wynn) Edith and Phillip Flowers once had good jobs, nice vehicles -- "we didn't have to worry about nothing," Edith said. But after Phillip went on disability and Edith was laid off, the couple lost their home. They now are raising their four grandchildren on less than $1,500 per month. (Bridge photo/Lance Wynn)

Edith and Phillip Flowers once had good jobs, nice vehicles -- "we didn't have to worry about nothing," Edith said. But after Phillip went on disability and Edith was laid off, the couple lost their home. They now are raising their four grandchildren on less than $1,500 per month. (Bridge photo/Lance Wynn)