Michigan seeks 'sweet spot' on small businesses

Most new jobs are created by small businesses, right?

That’s long been the perception perpetuated by small-business advocates and politicians from the local level on up to the White House.

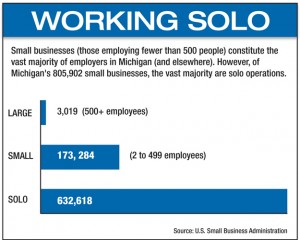

The reality isn't so neat. While federal statistics show small businesses accounted for 65 percent of all new jobs in the United States between 1993 and 2009, most small firms don’t create any jobs at all beyond that of "owner."

Of the 26.9 million large and small businesses in the nation in 2009, about 21 million of them were sole proprietorships with no employees, according to the U.S. Small Business Administration.

While those numbers are impressive, business development experts consulted by Bridge say sole proprietorships are not a particularly good thing. One argues that many of the self-employed were victims of layoffs who could not find new jobs -- a circumstance he calls "forced entrepreneurship." These economic refugees found their way into freelancing and consulting -- and became business owners who are unlikely to create any additional jobs, goes his theory.

Michigan leaders, though, are looking to the other group of small businesses -- those larger than sole proprietorships -- to expand their ranks and expand the state's economy.

Small is more than one size

The U.S. Small Business administration defines a small business as one that has fewer than 500 employees.

In Michigan, almost 130,000 of the 228,393 jobs added in the private and nonprofit sectors between 1995 and 2009 were sole proprietorships. The rest were in businesses with between two and nine employees, according to data compiled by the Edward Lowe Foundation in Cassopolis, which promotes entrepreneurship through research and educational services to small companies.

Meanwhile, businesses with more than 500 workers in the state shed 286,626 jobs between 1995 and 2009, according to the Lowe Foundation’s YourEconomy.org website. Many of those newly unemployed found themselves in the category "self-employed" because they couldn’t find new jobs, a phenomenon Lowe Foundation Executive Director Mark Lange calls “forced entrepreneurship.”

As Michigan recovers from what some called a “lost decade” in which the state lost 800,000 jobs, Gov. Rick Snyder’s administration is counting on small businesses to lead job growth.

As Michigan recovers from what some called a “lost decade” in which the state lost 800,000 jobs, Gov. Rick Snyder’s administration is counting on small businesses to lead job growth.

“These small businesses are going to be our economic base,” said Tom Rico, manager of economic gardening support services at the Michigan Economic Development Corp.

“That’s the future and that’s where we’re going to find the growth,” he said. “It’s not going to be the big-bang project.”

Tax code goes small

Michigan has oriented its business tax structure to favor smaller companies.

Last year, the Legislature and Snyder replaced the state’s cumbersome Michigan Business Tax, which taxed profits and sales revenues, with a 6 percent Corporate Income Tax.

But the tax is levied only on “C” corporations, which have stockholders and tend to be larger companies. Sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability corporations and “S” corporations are exempt from the tax.

In fact, only 41,300 of the 136,700 businesses that were required to file MBT returns are subject to the new business tax, according to the Treasury Department. The new levy, which cuts business taxes by $1.7 billion, took effect in January.

The Michigan Economic Development Corp. still woos investment and jobs from big businesses outside of Michigan, as Snyder’s predecessors did for many years. But the MEDC’s main thrust now is helping existing companies grow, a concept known as “economic gardening.”

The aid includes connecting companies to experts who can help them with marketing, finance, talent acquisition and a host of other issues faced by small businesses. Bolstered by data from the Lowe Foundation, the Snyder administration is especially focused on promoting growth in so-called “second-stage” companies.

These are businesses employing between 10 and 99 workers, and generating annual sales of up to $100 million.

Athough most of the job growth in Michigan over the past 15 years or so has come from first-stage companies employing two to nine workers, Lange said the statistic is misleading.

Second-stage companies employed 1.26 million workers in Michigan in 2009, more than any other business class. They employed more than twice as many workers as large companies and 30 percent more workers than first-stage companies.

And when the economy is growing, as it is now, second-stage firms tend to experience faster growth than smaller ones, Lange said.

From 1995 to 2000, years when Michigan was in a jobs boom, second-stage companies added 110,067 jobs, more than any other small-business segment.

Second-stage companies are in “the sweet spot” of job growth, said Rob Fowler, president of the Small Business Association of Michigan.

But he and Lange agree that second-stage companies face significant growth issues as they near 100 employees -- such as the need for more sophisticated marketing, financial and human resources functions. Those challenges can keep these businesses from growing into the third-stage companies that have up to 499 employees.

From the state's perspective, it’s important for companies to grow into that third stage because larger firms generally offer higher wages and benefits, and provide a wealthier economic base for their communities.

One state business group lobbyist said an economic development strategy that’s focused on helping existing Michigan businesses grow is a no-brainer.

“Any business owner knows it’s a lot easier to keep customers you have than go find new ones,” said Charles Owens, director of the National Federation of Independent Business-Michigan. “I think this is a good approach. We’ve neglected businesses that are already here.”

Touting the home team

In the meantime, Fowler’s association has launched a public-relations offensive to elevate the image of small business in the state. Its Michigan Small Business Jobs Insight is a website that tracks small business job growth in the state.

The site reported more than 3,000 new small business jobs in Michigan through mid-April.

Fowler explained SBAM had been talking about such an initiative for years, but the idea took on a new urgency after Snyder asked SBAM members to create jobs during a speech to the group’s annual meeting last year. The governor was facing criticism at the time from Democrats and others that his business tax cut was a giveaway to “fat cats” that wouldn’t produce jobs.

“We’re careful not to call it data. It’s not,” Fowler said about his website. “Data lags what’s going on in the economy. This is the story of what’s happening in Michigan right now.”

Rick Haglund has had a distinguished career covering Michigan business, economics and government at newspapers throughout the state. Most recently, at Booth Newspapers he wrote a statewide business column and was one of only three such columnists in Michigan. He also covered the auto industry and Michigan’s economy extensively.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!