Labor belabored: MEA losing members, losing fights. Will it lose its grip?

Michigan’s largest teachers union is struggling to keep a toehold as change-minded foes with growing momentum seek to topple the MEA -- one of the state’s traditional political giants.

The 152,000-member union’s finances are deteriorating. Its growth strategy is uncertain. And it faces an unrelenting political offensive by opponents who see the MEA’s position and worldview as hindrances to Michigan’s future.

“That is the unfortunate reality of the moment,” said John Austin, the Democratic president of the State Board of Education. “There’s a political ideology out there that says everything would be better if the traditional delivery agents of education were diminished.”

Such traditions are coming into conflict with parent and citizen expectations, however. Statewide polls in 2012 found more than half (59 percent) gave Michigan public schools a “C” or worse for their work; only 7 percent judged them with an “A.”

The MEA’s largely Republican foes point to lagging student achievement, decades of unchecked decline in urban schools and the union’s hearty support of Democratic Party fortunes as reasons to reconsider the MEA’s role – and to deliver unapologetic thumpings to teacher unions at every turn.

MORE COVERAGE: Long-simmering GOP-MEA war intensifies going into 2014

“If you look at it through a business lens, the MEA has had no real competition and has allowed themselves to be less responsive to their members,” said Ari Adler, spokesman for the House Republican Caucus. “With Right to Work, they are afraid of competition and they are afraid of being held accountable by their members.”

The outcome of this clash, which pits the MEA and the much-smaller Michigan arm of the American Federation of Teachers against powerful interests seeking to continue to zap the power of public sector unions could determine the direction of K-12 education policy in Michigan for years.

Among those forces are RTW advocates, including the Mackinac Center for Public Policy and Gov. Rick Snyder, who is promising a continued major overhaul of public education.

“We are the only one with the collective power to fight back,” counters MEA spokesman Doug Pratt said. “The MEA has been around for 160 years because people care about public education.”

MEA coffers large, but shrinking

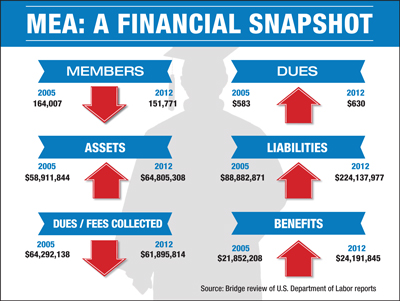

No one is suggesting that the MEA, which last year took in $122 million in receipts and has nearly $65 million in assets, is about to go under.

But it faces serious challenges in the most hostile political climate toward the union in memory:

--The union is rapidly burning through cash to pay rising expenses and exploding staff retiree costs, which total more than $200 million — three times the union’s total assets.

--Membership has fallen nearly 7.5 percent over the past seven years (from 164,000 to 152,000) as school districts have laid off staffers in response to declining enrollment and tightening budgets.

--Michigan has fewer students to teach. From a recent high of 1.71 million in 2005, statewide enrollment is expected to dip to 1.53 million by next year. And, with changes in state policy, more of those remaining students are expected to attend largely non-unionized charter schools.

--The MEA is in the midst of an epic political losing streak. Its preferred gubernatorial candidate got waxed in 2010. Its favored political party has no power in the Legislature. And it spent millions of dollars supporting a failed ballot proposal in 2012 that would have enshrined collective bargaining rights in the constitution.

--Even its fabled lobbying power – backed by members in every legislative district in the state – failed to prevent passage of Right to Work last December.

MEA and AFT Michigan officials say they are responding to these threats by monitoring expenses, constantly communicating with their members on the value of union membership and positioning themselves as the defenders of Michigan’s long-establishment public education system.

Leaders of the two unions also say they’re working more closely than ever on political activities. Among other things, the unions are developing a strategy to overturn Right to Work, said AFT President David Hecker.

“There have long been obstacles in our way,” he said. “We’ve been able to overcome these things before and we’ll do it again.”

But of the two unions, the MEA has long been the 800-pound gorilla. And the gorilla is ailing.

MEA’s ironic burden: Exploding legacy costs and big cash burn

In the past seven years, the MEA has lost more than 12,000 members and seen its unfunded liabilities for pensions for its staffers balloon from $67.8 million to $129 million. (These are liabilities for internal union employee pensions. Classroom teachers and school personnel are covered by a separate statewide pension system.)

In addition to the unfunded pension liability of $129 million, the union is on the hook for another $79.5 million in future retiree health care benefits.

Ironically, the MEA faces the same kinds of internal financial pressures on benefits with its own staff that it has encountered in negotiations with local school districts for years.

The union also is rapidly burning through cash to fund operations, according to financial reports it must file with the U.S. Department of Labor.

It ended last year with $30.6 million in cash, $12.2 million less than it had on hand at the beginning of the year. However, that was the first time in a decade that its cash reserve had shrunk.

Pratt attributed the cash burn to funding obligations for retiree benefits, the cost of maintaining programs, spending on last year’s collective bargaining ballot proposals and declining revenues.

Dues revenue fell nearly $1 million, from $62.8 million in 2011 to $61.9 million last year. Dues revenue hasn’t been that low since 2003 when the MEA collected $50.4 million. The next largest receipt category --- “other” at $39.5 million – mainly reflects a payroll function for its subsidiaries, not actual revenue.

Those numbers paint a troubling picture of the MEA’s financial condition, one expert said.

“The trend here is definitely negative,” said Michael Boudreau, managing director of O’Keefe, a Bloomfield Hills-based company that provides financial turnaround services for corporate and public sector clients.

“Its retirement plans are underfunded; it’s burning through cash; and there’s a risk they’ll lose membership (under RTW), which will exacerbate the situation,” he explained.

Boudreau, who reviewed MEA financial statements at Bridge’s request, doesn’t think the union’s compensation and administrative costs were out of line for an organization of its kind. But he said payment of the union’s benefit costs were an unsustainable 26 percent of total expenses last year.

“That number jumps off the page,” he said. “It’s definitely cause for concern.”

MEA Executive Director Gretchen Dziadosz said the unfunded liability for retiree benefits of the union’s 250 active employees and almost 800 staff retirees is “obviously a big number and a concern.” But she expects the liabilities to decrease over time.

MEA President Steve Cook explained the union is getting some relief on pension funding through a 2012 federal law that gives employer-provided defined benefit plans more time to address funding shortfalls.

Last year, the MEA assessed members as much as $67.40 a person, depending on salary level, to help fund its pension plan. That fee – above the standard annual dues -- has been reduced to a maximum $50 this year because of the new law.

But the MEA’s 1,000-member Representative Assembly voted just last month to boost dues by $5 to $640 a member.

The union, like the school districts it negotiates with, has cut staffing, too. Its current work force of 250 is down 31 percent from the 362-employee force from 2001.

“We always look at the budget,” Dziadosz said. “We’re always re-evaluating as we bargain collectively with our staff.”

Still, Boudreau said the MEA’s huge and growing liability likely will force the union to reduce retiree health benefits and change its pension from a traditional defined benefit plan to a 401(k) type plan, at least for new employees.

“It’s a new world out there,” he said. “The public sector is slow to adopt these measures.”

MORE COVERAGE: As Right to Work takes root, MEA faces rough lessons from Wisconsin

AFT Michigan is in relatively better financial shape. Its membership has been hovering around 25,000 for most of the past decade and it reported no retiree health care liability for its approximately 50 employees in its 2011 annual report, the latest on file at the Labor Department.

Hecker said most of the union’s employees once worked for local school districts and are eligible for retirement benefits through them.

Dziadosz, who assumed the MEA executive director role in 2012, is described by some who know her as a savvy, hard-working insider.

“She’s solid,” said Tom White, the retired executive director of the Michigan School Business Officials. “She’s a moderating influence at the MEA.”

Observer sees big losses ahead for MEA

Prior to accepting the union’s top management job, Dziadosz had served at MEA for more than 25 years, working her way up to director of its “UniServ” staff.

UniServ staffers are the heart of the MEA’s operation. They aid local MEA units in contract negotiations, filing grievances, dealing with teacher tenure issues, helping to develop school improvement plans and other issues.

“At one time, there was a bit of seasonality to bargaining, but those days are long past,” explained Dziadosz. “In essence, (UniServ staffers) are the local face of the MEA to our members and are charged with assisting local associations and members with whatever their professional needs may be.”

About two-thirds of the MEA’s staff work as UniServ directors and field assistants from 40 field offices scattered across the state.

MORE COVERAGE: MEA faces breakaways, poaching of locals

The operation has long been considered a major strength of the MEA. But in recent years, some local units have complained that the service has become too costly and isn’t serving them well.

Among those are teachers in Roscommon Area Schools, which dropped out of the MEA last year and formed their own independent union.

“They were never involved in any significant way in helping us negotiate contracts,” said Jim Perialas, president of the new Roscommon Teachers Association.

“I think (the MEA) is likely to lose a lot of members,” White said.

White, who now works as a labor negotiator for school boards, said the MEA is particularly vulnerable to losing lower-paid school staff support members who have taken concessions in recent years and may want to save money by not paying dues.

AFT Michigan is less vulnerable, he said, because its dues are about a third as much as the MEA’s dues.

MEA’s Cook said it could be years before the group feels the full effect of RTW because “hundreds” of union locals signed long-term labor contracts before the law took effect in late March. (Union members are not allowed to stop paying dues or agency fees until contracts negotiated before the law took effect expire.)

“We’re not seeing that groundswell of noise in the system that says we’re leaving,” he said.

MEA’s survival strategy?

While MEA’s short-term strategy to deal with Right to Work became quickly evident this year, how the union handles long-term demographic and political shifts is much less clear.

MEA and AFT Michigan are not considering a merger, but are working more closely than ever on public education advocacy, AFT’s Hecker said.

And the AFT has been aggressive in trying to organize charter schools in Michigan and other states. In February, 140 teachers at the Cesar Chavez Academy in Detroit voted to join AFT Michigan.

But Chavez is just the second charter in the state to be organized by AFT Michigan.

Pratt of the MEA said his union has organized fewer than a dozen charters -- and none in recent years.

“It's hard to organize charters because their staff turnover is so high,” he said. “By the time you get a critical mass together, many move on or are let go.”

MEA and AFT officials say the key to their sustainability will be in providing excellent service to their members.

“In a Right-to-Work world, it’s all about communicating with our members,” Pratt said. “We’ve been doing this for many years now — talking about the advantages of being members and the value of public education in general.”

White, the school board labor negotiator, said he hopes the MEA, in particular, can overcome its serious financial challenges.

“As a management guy, I’m not reveling in this,” he said. “They’re a balancing force and a powerful advocate for public education. I wish them well in how they sort this out.”

Rick Haglund has had a distinguished career covering Michigan business, economics and government at newspapers throughout the state. Most recently, at Booth Newspapers he wrote a statewide business column and was one of only three such columnists in Michigan. He also covered the auto industry and Michigan’s economy extensively.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

(Bridge illustration/A.J. Jones)

(Bridge illustration/A.J. Jones) Wisconsin offers a troubling lesson for the MEA and AFT Michigan. Privately, MEA officials call Wisconsin’s 2011 ban on most collective bargaining by public sector unions “Right to Work on steroids.” Membership in public sector unions there is down more than 20 percent in the past two years.

Wisconsin offers a troubling lesson for the MEA and AFT Michigan. Privately, MEA officials call Wisconsin’s 2011 ban on most collective bargaining by public sector unions “Right to Work on steroids.” Membership in public sector unions there is down more than 20 percent in the past two years. MEA currently has about 35,000 retirees and about 115,000 active members. Of the active members, about 30,000 are support staff, 10,000 are higher education faculty and about 75,000 are K-12 teachers.

MEA currently has about 35,000 retirees and about 115,000 active members. Of the active members, about 30,000 are support staff, 10,000 are higher education faculty and about 75,000 are K-12 teachers. MEA Executive Director Gretchen Dziadosz

MEA Executive Director Gretchen Dziadosz MEA President Steve Cook

MEA President Steve Cook AFT-Michigan President David Hecker

AFT-Michigan President David Hecker