3-D printing is new way to make things, in state where manufacturing thrives

The 3-D printer is no Star Trek replicator, but it’s pretty darn close. The futuristic machine could well be the next big thing in manufacturing, and substantially change the way we make things in southern Michigan for the first time since Henry Ford began making the Model T at the Highland Park plant in 1910.

The assembly line has been mechanized, robotized and computerized, but it still follows essentially the same process of pulling products along from station to station where workers perform the same task throughout their workday.

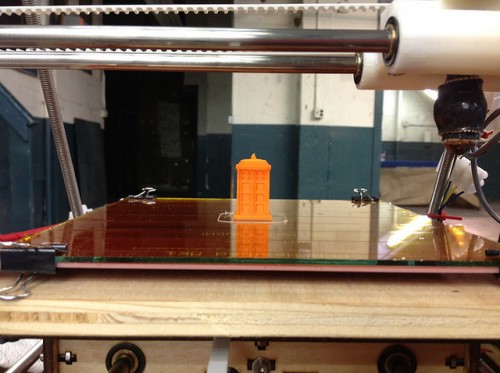

But 3-D printing is a nascent technology that allows users to make things in much the same way the printer attached to your computer does with ink and paper. The 3-D printer – or fabricator, as some call it – moves similar to the way a normal printer head does. However, instead of putting ink on a page, it builds objects layer by layer as it goes back and forth. The “ink” in the fabricator can be made from corn starch, soft or hard plastics, even metals ‒ anything that can be ground into a powder.

“Yes, 3-D printing is amazing and will have consequences like crazy,” says Frithjoff Bergman, a retired University of Michigan professor. “The next great wave of technology that includes 3-D printing will make manufacturing in a community setting far more possible than it has so far.”

The machines have been around about two decades but have mostly been too expensive for most. Cheap desktop versions are available, but aren’t good for much more that making trinkets and demonstrating the technology’s possibilities. However, some tech watchers say 3-D printers will become much more accessible in 2014, because patents on key parts of the technology will run out and make large, industrial grade fabricators much cheaper. Others say it will be a more gradual process as a series of patents run out over the next several years. Whether it’s next year or in 10 years, fabricators are set to proliferate.

A patent was a key issue in the Ford development too. In the early years of automaking, inventor George Selden held a patent on the internal combustion gasoline engine. All commercial automakers had to pay a fee to the Association of Licensed Automotive Manufacturers which had an agreement with Selden. The patent fee made automobiles so expensive they were mainly considered playthings of the rich. Ford sued and eventually won the right to use the engine without paying royalties. With enhanced profitability the auto industry exploded. It sounds like the same thing could happen with 3-D printing

What impact will that have on us, the people whose economy is based on making things? Fabricators are not practical for mass production. However they have revolutionized the process for building models that can later be mass produced in more traditional ways. New products can be developed and brought to market faster with fabricators, but it’s in craft markets and smaller communities that the machines will make a bigger impact. Consumers will be able to customize programs to make one-of-a-kind creations – whether that is a set of dinnerware, shoes, or small tools, even consumer electronics.

“We will be able to directly produce things a family needs,” says Blair Evans, director of Incite Focus, a fabricating laboratory – or FabLab – on Detroit’s east side.

Incite Focus has a fabricator and other support technologies that demonstrate the possibilities. The fabricator can make a precision-molded plastic article, and other technologies can add electronics to make components that fit many machines. Students from the Blanche Kelso Bruce Academy charter school, founded by Evans, learn to program and use the 3-D printer there.

Barbara Stachowski, a local writer and social activist, recently visited Stuttgart, Germany, to visit a site where fabricators were used to make the components of an easily assembled electric motorcycle. She observed a youth project where over a three-day period a group of girls collected used plastic cups, and learned to program the fabricator to make bracelets and other small items from the cups.

“It’s encouraging to see that you don’t need eight years of college or a PhD to put those things to use,” says Stachowski. “We have a lot of people who are technically savvy, because of the nature of what Detroit was. There is an opportunity for that printer to play a big role.”

Rather than build things with thousands of people in mega industrial facilities, they will be made by a few people in small rooms. That’s going to be a big difference.

Larry Gabriel is a Detroit-area writer who was named Best Columnist by the Association for Alternative Newsmedia in 2012. He believes there is wisdom in blues lyrics, and that the best brunch is poached salmon, scrambled eggs and avocado.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

JUST PRESS PRINT: Whether it's used to make trinkets or custom-designed machine parts, 3-D printing will change manufacturing. (Photo by Flickr user theycallmebrant; used under Creative Commons license)

JUST PRESS PRINT: Whether it's used to make trinkets or custom-designed machine parts, 3-D printing will change manufacturing. (Photo by Flickr user theycallmebrant; used under Creative Commons license)